Eagleton’s formulations are especially useful on account of his all-but-explicit connection of criticism with the practice of close reading a poem. This connection provides a key to understanding the current situation. To see why, let’s first remember that, like history and philosophy, but unlike post-Enlightenment disciplines such as anthropology, linguistics, or biology, criticism is an intellectual pursuit that has in fact been around since the time of those ancient Greeks who coined the term. Indeed, criticism dates back almost as far in the Western tradition as the invention of writing and theater, further than Aristotle’s Poetics (fourth century BCE), which already makes reference to still earlier ways of inquiring about poetic objects—earlier, even, than those of Aristotle’s teacher Plato. This fact alone ought to give pause to those who expect criticism’s imminent demise. It is true that in English departments around the world, a course in the history of criticism that begins with Plato and Aristotle and comes down to the present is no longer the standard offering it was eighty, fifty, or even thirty years ago. It may thus be reasonable to speculate that criticism has undergone some change in status—or at least in “function”—within the last two or three academic generations. Post-structuralism, feminism, psychoanalysis, Critical Race Theory: these have all shaped what it means to do criticism in recent decades. Yet, altering its function is something that criticism has been recognized as doing for a long time, certainly since Matthew Arnold’s famous 1864 essay “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time.”

In that seminal essay, Arnold argued that Romanticism had decisively changed the game for those who call themselves critics by casting the creative and critical principles in opposition, with perhaps the further insinuation that the latter was parasitical on the former. Arnold thought this story misleading in that it underestimated the role of criticism in cultivating the ground on which poetry flourishes in the first place. “The burst of creative activity” in English Romanticism, he wrote, “had about it in fact something premature”: “the English poetry of the first quarter of this century, with plenty of energy, plenty of creative force, did not know enough.” Diminished by both the French Revolution and English utilitarianism, the Romantic poets had thus left behind even more diminished prospects for poetry. Criticism in 1864 thus needed all the more to provide the environments of thought and knowledge—what Arnold called simply “culture”—that might allow poetry to flourish anew. 6We needn’t accept either Arnold’s diagnosis or his specific prescription to agree with the idea that criticism changes function over time. Arnold’s own “time” is not so distant from ours, but, taking a longer historical perspective, we see that criticism has changed in many ways over its long history. There have been moments when criticism has been more aligned with rhetoric and communication (as in the case of ancient Rome), or more aligned with poetics and craft (as in Aristotle’s Greece), or more interested in the rules of art (as in neoclassicism), or more oriented toward the author’s life and values (the nineteenth century), or more oriented toward “the poem itself,” as T. S. Eliot said criticism must be in his twentieth century. 7

Eliot’s notion of “the poem itself” came to be a kind of shibboleth for what is called the New Criticism, a movement inspired by the important early-twentieth-century British thinker I. A. Richards. Richards boldly established literary criticism at the center of an ambitious campaign to rehabilitate cultural values in his contemporary Britain, and he established the study of poetry at the center of literary criticism. The story of how he set out to achieve this goal is by now a familiar one. In 1925, the year after he published Principles of Literary Criticism , he undertook some far-reaching pedagogical experiments requiring students to respond in writing to clusters of poetic texts from which all markings of date or authorship had been removed. He attracted to his project some of the best literary minds of the period: William Empson, Muriel Bradbrook, and Eliot himself among them. Richards’ poetry courses had such an enormous following that classes had to meet in the streets of Cambridge for the first time in centuries. He published his findings from these classroom experiments in Practical Criticism (1929), one of the few genuinely seminal works of criticism in English since the nineteenth century. 8

With these books, and through this group, and not least by the powerful force of his own charismatic example, Richards changed the way literature was studied. He made criticism the primary activity of the field of English, and he installed the notion of “close reading” at the center of that field. The American New Critics of the 1930s—Cleanth Brooks, Robert Penn Warren, and W. K. Wimsatt—all acknowledged the leadership of Richards in showing them the way forward. In America, this enterprise of “practical criticism,” with the study of lyric poems in isolation, indeed became a centerpiece of liberal education for decades. And one of the most important features of this program was that it implicitly identified itself as a kind of activity or doing, for practical also derives from a Greek word ( prattein ), which means, precisely, to do.

The commission to write a book about how to do criticism thus necessarily returns me to this question of “practical criticism.” It will become clear, however, that I assign practical criticism a somewhat different function from that of Richards. It is one that builds upon Richards’ idea but enlarges the sphere in which criticism is called on to do its work. 9My aim is to illuminate how practical criticism might be effectively sustained in our moment partly by understanding its application to poetics in an expanded field of reference . I will explain what I mean by that in due course. By way of introduction to this book and this mission, however, I turn first to the task of providing a sense of what it means to “do criticism” in the sense that Eagleton intends, just to provide a reminder of what criticism feels like when, to adapt a phrase from Keats, it is proven upon the pulses. I will then broaden the horizon of poetics beyond the study of lyric poetry to include not only literature broadly considered but also film and the motion picture arts. I wish not only to show a viable path forward for criticism “at the present time” but also to suggest that doing without criticism is not only imprudent but also perhaps impossible.

1.2 Two Thought Experiments

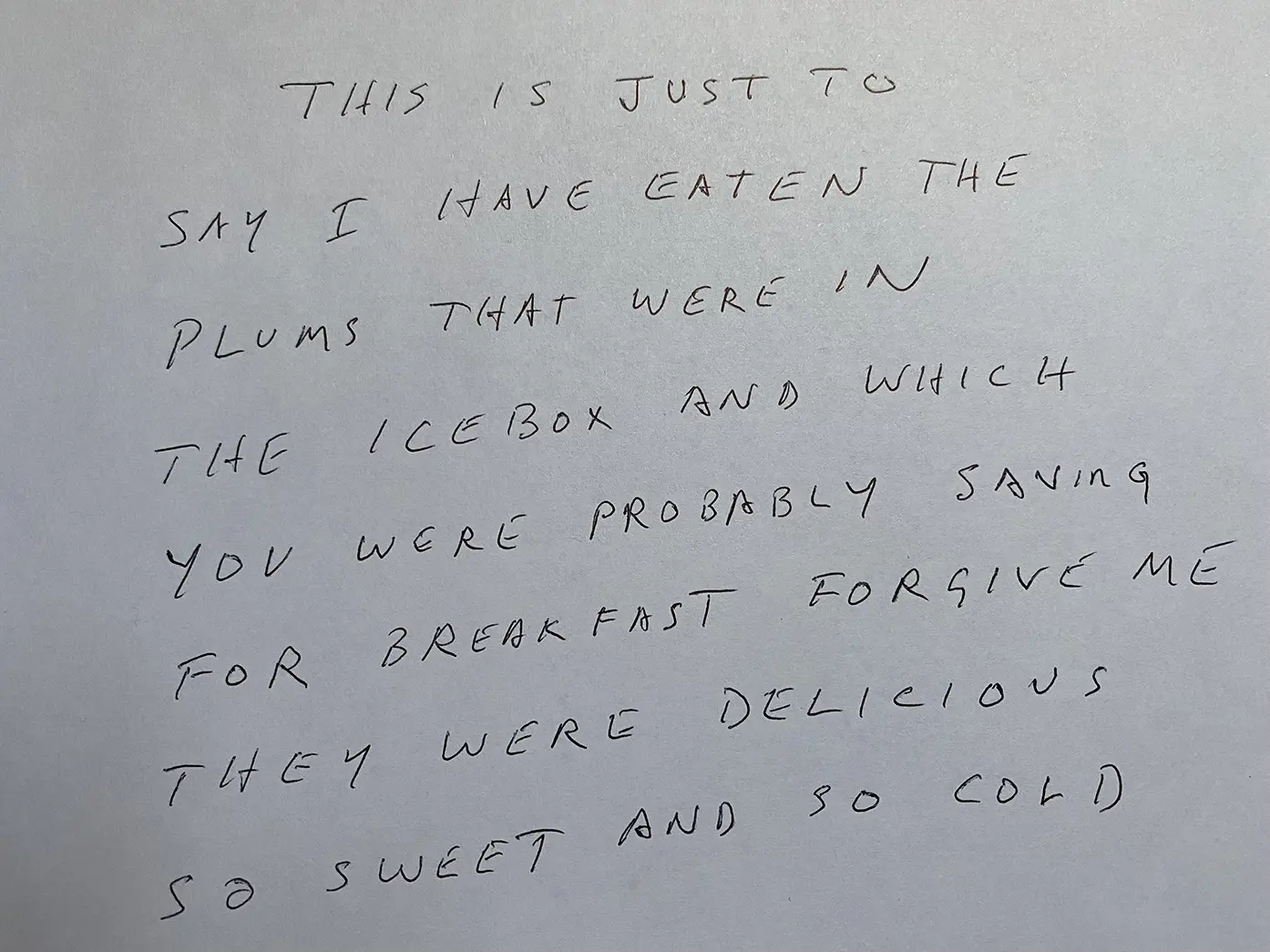

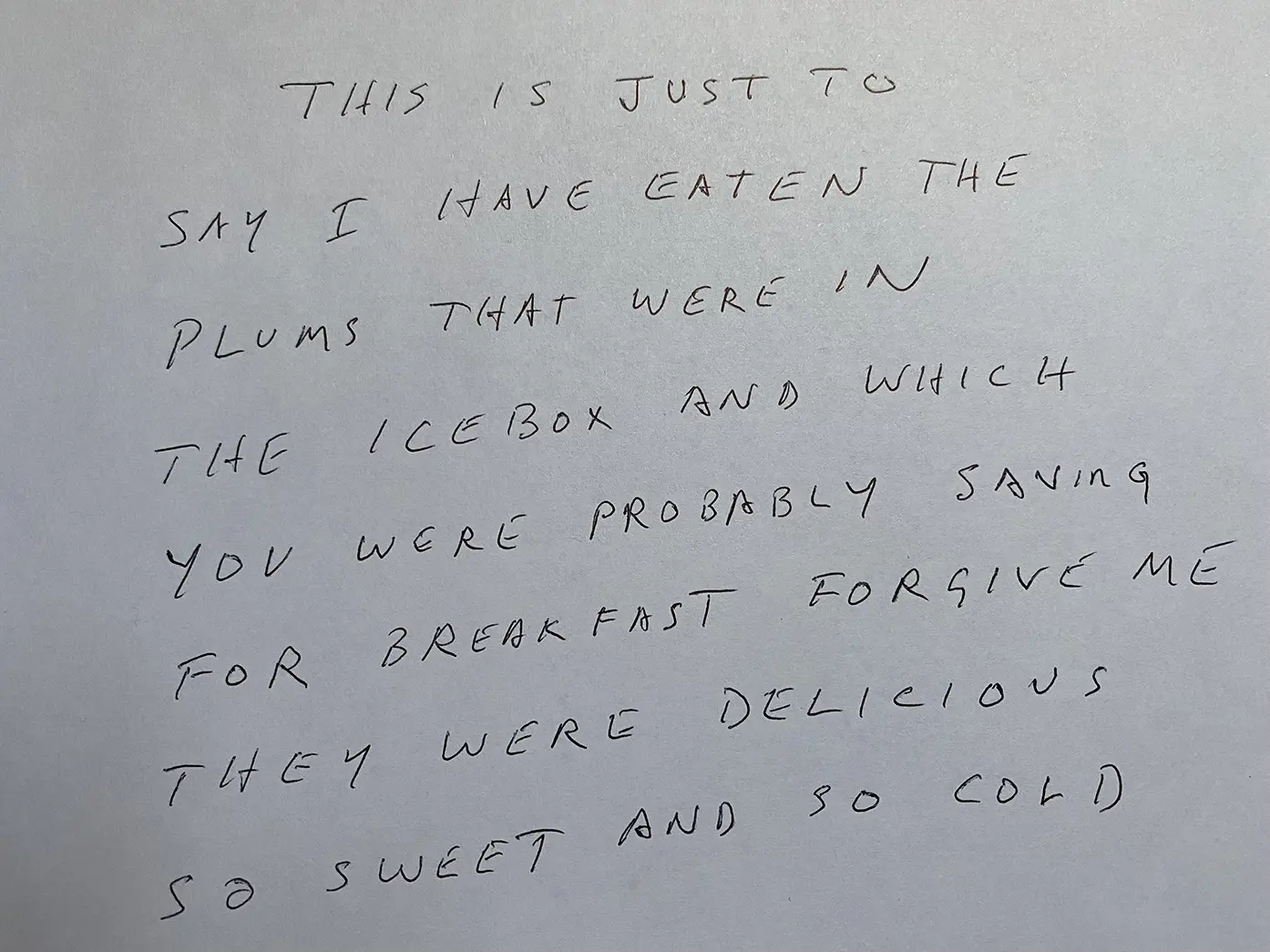

In the spirit of Richards’ experiments in criticism, then, let us now attempt a thought experiment of our own. Imagine that you share a refrigerator with someone—a sibling, a roommate, a partner, or a spouse. One groggy morning you go to open it, and you find stuck to its door the following message (Figure 1.1):

FIGURE 1.1 Prose transcription of Williams Carlos Williams’ “This is Just to Say,” handmade for this book by its author.

It is a fair guess you might be a little annoyed by this note, and perhaps a little puzzled. It might be said to raise questions. Why is the person who stole your plums telling you how good they tasted? Is this a confession or a declaration, an apology or a taunt? The answers to such questions would probably depend upon what terms you were on with your sibling, roommate, partner, spouse, or child. So would your general response: bemusement, irritation, anger. You might do something on account of this message. You might steal your sister’s yogurt, confront your roommate, ask your partner if you have done something to deserve this bizarre treatment, scold your child. You might even laugh it off. But such a message doesn’t call on you do anything with it. It doesn’t call on you, that is, to “do criticism.” Its questions tend to be of a different order from those of criticism.

Читать дальше