"Yes, S'phiry Ann is er oncommon name," she would say, not without a touch of complacency, "but her pap give it tu her. She was a month old to a day, when that travelin' preacher come through here an' held meetin' fer brother Dan'l on Sunday. He preached mos'ly about them liars droppin' dead at the 'postles' feet, an' Standnege came home all but persessed about it, an' nothin' ed do but he mus' name the baby S'phiry Ann instead er Sary Ann as we had thought. He 'lowed it sarved them onprincipled folks right to die, an' he wanted somethin' ter remin' him o' that sermont. Well, I ain't desputin' but it was right, but I tole Standnege then, an' I say so yit, that ef all the liars in the world war tuk outen it, thar wouldn't be many folks left."

S'phiry Ann had heard of the fate of the Sapphira figuring in sacred history; it had been deeply impressed on her mind in her tenderest years, and might possibly have left a good impression, for she grew up a singularly truthful, upright girl. Just now, as she leaned against the mantel and stared at the fire, her face wore an unwontedly grave expression.

"Folks as set themselves up ter be better'n they ekals air mighty apt tu git tuk down, S'phiry Ann," said her mother, evidently resuming a conversation dropped a short time before.

"But I ain't a-settin' up ter be better'n my ekals, ma," said S'phiry Ann, gently but defensively.

"It 'peared like nothin' else yiste'day when you so p'intedly walked away from Gabe Plummer at meetin', an' it the fust time you had seed him since comin' from yer aunt Thomas over in Boondtown settle*mint*. Thar ain't no call ter treat Gabe so."

"But ain't we hearn he's tuk up with them distillers on the mountains?" said the girl in a low tone, a deep flush overspreading her face.

"Yes, we hev hearn it, but what o' that? Many a gal has tuk jes' sech."

"An' glad to get 'em, too," snapped Polly sharply, stopping to tie up a broken thread.

"Gabe Plummer is er oncommon steddy boy. He's er master hand at en'thing he wants ter do, an'—"

MR. STANDNEGE.

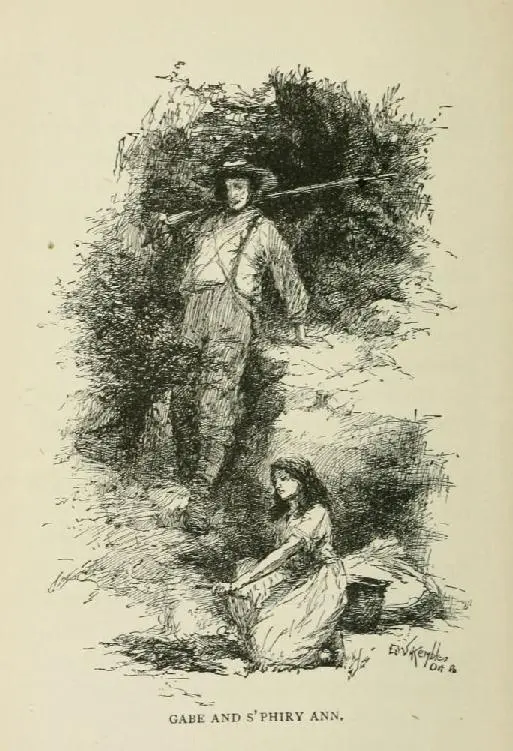

But S'phiry Ann did not linger to hear the full enumeration of her lover's virtues. Hastily balancing the bundle of clothes on her head, she took up the blazing torch, and hurried to the spring, a crystal-clear stream, running out of a ledge of rock, and slipping away through a dark ravine to the river. If she imagined she had escaped all reproaches for her reprehensible conduct the day before, it was a sad mistake. Hardly had the fire been kindled and the rusty iron kettle filled with water when a young man came treading heavily through the laurel thicket above the spring, leaped down the crag, and saluted her.

"Mornin', S'phiry Ann."

"Mornin', Gabe," she said, blushing vividly and busying herself piling unnecessary fuel on the fire.

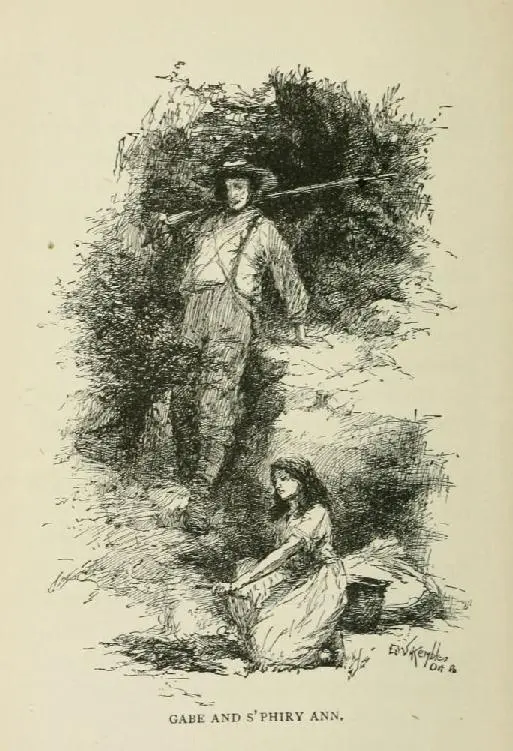

He was a fine specimen of the mountaineer, lithe, well-made, toughened to hardy endurance, with tawny hair falling to his collar, and skin bronzed to a deep brown. He wore no coat, and his shirt was homespun, his nether garments of coarse brown jeans. He carried a gun, and a shot-bag and powder-horn were slung carelessly across his shoulders.

"I knowed you had a way er washin' on Monday, so I jest thought bein' as I was out a-huntin' I'd come roun'," he said, sitting down on the wash-bench, and laying the gun across his lap.

"You air welcome," she said, taking a tin pail and stepping to the spring to fill it.

"I wouldn't 'a' lowed so from yiste'day," darting a reproachful glance at her.

She made no reply.

"What made you do it, S'phiry Ann?" he exclaimed, no longer able to restrain himself. "I ain't desarved no sech; but if it was jes' ter tease me, why—"

She arose with the pail of water.

"No, it wasn't that," she said in a low tone, her eyes downcast, the color flickering uncertainly in her face.

"Then you didn't mean what was said that night a-comin' from the Dillin'ham gatherin'," he cried, turning a little pale. "Mebby it's somebody over in Boondtown settlement," a smoldering spark of jealousy flaming up.

"It's the 'stillery, Gabe," she said, and suddenly put down the pail to unburden her trembling hands. "You hadn't ought ter go inter it."

"But the crap last year made a plum' failure," he replied excusingly, his eyes shifting slightly under the light of hers. She was standing by the spring, against a background of dark green, a slanting sunbeam shifting its gold down through the overhanging pine on her dark, uncovered head, lighting up her earnest face, lending lustrous fire to her eyes. The scant cotton skirt and ill-fitting bodice she wore could not destroy the supple grace of her figure, molded for strength as well as beauty.

"The crap wusn't no excuse, an' if you mus' make whiskey up thar on the sly, I ain't no more tu say, an' I ain't no use fer ye."

"Yer mean it, S'phiry Ann?"

"I mean it, Gabe."

"Then you never keered," he cried with rising passion, "an' that half-way promise ter marry me was jest a lie ter fool me—nothin' but a lie, I'll make it if I please," bringing his down on the bench with a fierce blow.

"An' hide in the caves like a wild creetur, when the raiders air out on mountains?" she scornfully exclaimed.

GABE AND S'PHIRY ANN.

His sunburned face flushed a dull red, he writhed under the cruel question.

"They ain't apt ter git me, that's certain," he muttered.

"You don't know that," more gently. "Think o' Al Hendries an' them Fletcher boys. They thought themselves too smart for the officers, but they wasn't. You know how they was caught arter lyin' out for weeks, a-takin' sleet an' rain an' all but starvin', an' tuk ter Atlanty an' put in jail, an' thar they staid a-pinin'. I staid 'long er Al's wife them days, for she was that skeery she hated ter see night come, an' I ain't forgot how she walked the floor a-wringin' her hands, or settin' bent over the fire a-dippin' snuff or a-smokin'—'twas all the comfort she had—an' the chilluns axin' for their pap, an' she not a-knowin' if he'd ever git back. Oh! 'twas turrible lonesome—-plum' heart-breakin' to the poor creetur. Then one day, 'long in the spring, Al crep' in, all broke down an' no 'count. The life gave outen him, an' for a while he sot roun' an' tried ter pick up, but the cold an' the jail had their way, an' he died."

She poured out the brief but tragic story breathlessly, then paused, looked down, and then up again. "Gabe, I sez ter myself then, 'None o' that in your'n, S'phiry Ann, none o' that in your'n.'"

She raised the bucket and threw its contents into a tub.

Gabe Plummer cast fiery glances at her, the spirit and firmness she displayed commanding his admiration, even while they filled him with rage against her. Yes, he knew Al Hendries's story; he distinctly remembered the fury of resentment his fate roused among his comrades, the threats breathed against the law, but he held himself superior to that unfortunate fellow, gifted with keener wits, a more subtile wariness. The stand S'phiry Ann had taken against him roused bitter resentment in his soul, but the fact that he loved her so strongly made him loath to leave her. A happy dream of one day having her in his home, pervading it with the sweetness of her presence, had been his close and faithful companion for years, comforting his lonely winter nights when the wind tore wildly over the mountains, and the rain beat upon his cabin roof, or giving additional glory to languorous summer noons, when the cloud-shadows seemed to lie motionless on the distant heights, and the sluggish river fed moisture to the heated valley.

Читать дальше