There was a pleasant bustle in the castle courtyard throughout the following morning, and St. George watched the proceedings with interest. The captain of the archers brought him a bow, and this proved to be so much less powerful than the English weapon that the Knight thought it advisable to put in an hour’s practice at the archery butts. The arrival of the elephants drew him from that amusement. He had encountered elephants before—in the enemy’s ranks during some of his campaigns—but he had never seen specimens so magnificent as were these which the King of Silene had collected. There were forty of them, all giants of their kind, and from their towering shoulders great scarlet saddlecloths drooped nearly to the ground. The cloths were fringed with hundreds of little bells; and bells, again, hung from bands encircling each elephant’s legs; for the aim was to make the animals’ progress as noisy as possible. The grinning Indians perched upon the mighty necks carried horns of a curious, twisted shape. These, when blown, produced a sound not unlike the trumpeting of an elephant; and, when this happened, the great beasts would elevate their trunks and trumpet in reply. The gong beaters sat in small howdahs; and each carried, besides his metal disc and hammer, a heavy, spiked mace with which to strike at any dragon which might have the temerity to turn and attack the driving line. But this last, St. George was told, happened very rarely. He was amused to see that the enormous animals devoured greedily the little cakes which the Princess Cleodolinda offered to each: indeed, this docility of creatures which he had known only as raging war monsters struck him as most surprising.

Cleodolinda was enthralled by St. George’s description of the advance of an elephant line-of-battle, and marveled greatly that any army could defend itself against such an attack. St. George explained.

“You see,” he said, “the creatures are not brave individually. They need the support of their fellows in the line. When their riders are shot with arrows, the elephants, lacking guidance, can maintain that line no longer. It bends and divides, and then breaks up into single elephants rushing in every direction. These desire merely to escape from the battle; and the men of their own side, who try to drive them back to the attack, become the only sufferers.”

Here the conversation was interrupted by a clarion call from the castle, summoning all to a hasty meal. The sun was now high in the heavens, and there was no time to be wasted. Even the King, a notable trencherman, contented himself on this occasion with half a ham and two flagons of wine. St. George ate and drank even more sparingly; while Cleodolinda, who was wildly excited, could barely force herself to nibble the wing of a chicken. And so, with very little delay, they gathered again in the courtyard, and the procession set out for Dragon Wood.

Here the party divided. The elephant line filed away along the western border of the trees, while the others continued along the southern edge until they came to the eastern side. From this, rolling grassland descended gently to a valley, the bottom of which was out of sight. Beyond, the ground rose again, but the character of the country had changed. It had become a forbidding-looking territory of crags and rock-strewn plateau separated by gorges in which pine and thorn struggled for mastery. St. George, shading his eyes with his hand, saw that this desolate land swept away northward in a series of ridges until it ended in sunlit mist. In the immediate foreground there towered, faint and ethereal against the pale-blue sky, a shining conical peak.

“Queen Sophia’s land,” said the King’s voice in his ear. “And yonder is the extinct volcano.”

“It ceased to erupt two years ago, I think you said, sire.”

“Yes,” answered the King, “but it caused most of that desolation first. The earthquake six months back did the rest.”

A horn sounded remotely—a single, interrogative note from the other side of the forest.

“Ah!” cried the King. “That is to ask if we are ready. Come quickly. This way.”

They strung out along the eastern border of the forest, standing fifty yards apart, and about forty paces back from the trees. Then the King blew a single blast upon his own horn.

The note had scarcely died away when, at the distant side of the forest, there broke out an indescribable tumult, faint at first, but growing rapidly louder. St. George, listening intently, could distinguish the trumpeting of the elephants and the clanging of the gongs, mingled with shrill cries of “Hi! yah! Hi! yah!” But the little bells were too far away to be heard.

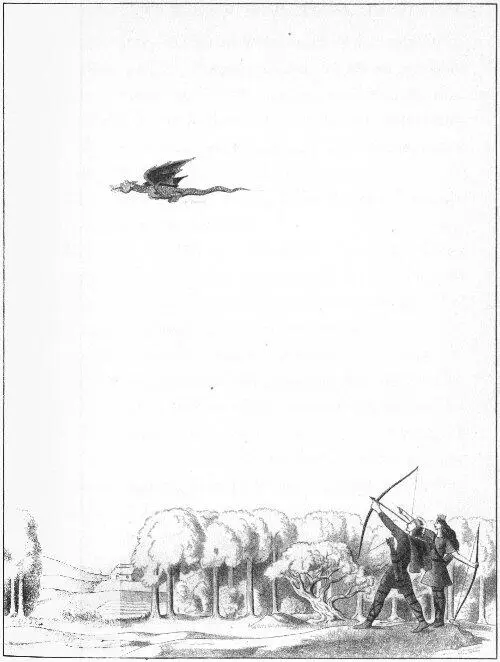

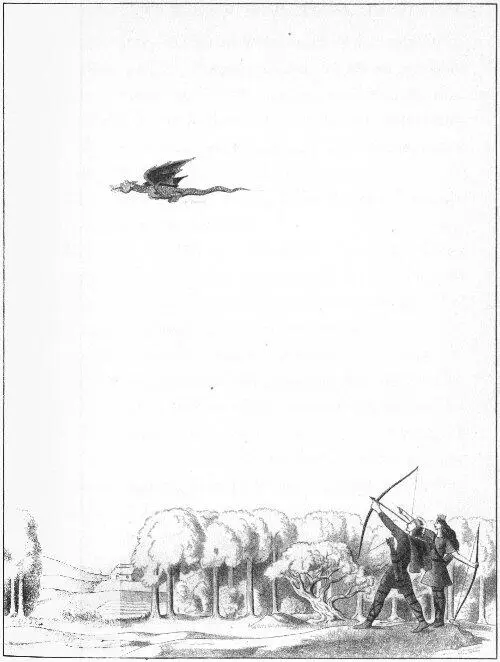

“Look! look!” cried the Princess suddenly. She was standing nearest to him on his right.

St. George raised his head. Threading its way through the distant, green treetops, and traveling at an incredible speed, there was coming toward them something which looked like a streak of golden light. As it reached the forest edge, it soared upward and revealed itself as an immense, lizardlike creature with long, gleaming body and broad, burnished wings. It shot over the head of the captain of the archers; and he, spinning round, let fly an arrow in pursuit. The shaft struck the creature in the lower ribs, burying itself to the feathers; and the dragon, somersaulting in the air, pitched headlong to the earth. It fell with a mingled crash and clang, and moved no more.

“Oh! good shot, Walter!” cried the Princess. The captain looked round and smiled.

Ding dong, ding dong. “Hi! yah!” Toot toot. Clang clang clang, came from the advancing line; and then, suddenly, the noise was drowned by a full-throated roar that echoed and re-echoed among the tree trunks.

“Dragon forward! Dragon for-r-ward!” shrieked the beaters. St. George saw another gleam approaching through the treetops. It sailed over him, and he turned and let drive. But, accustomed to the greater speed of the English cloth-yard arrow, he misjudged his distance allowance and shot too far behind. Thereupon, the Princess and Walter let fly simultaneously—and their arrows crossed in the dragon’s heart.

The next chance came to Cleodolinda, and she brought down her quarry very neatly. She was wild with delight, for this was a dragon she had killed entirely by herself—the first of which she could make that boast. Then a monster flew roaring over St. George, and this time he did not miss. The driving line was nearer now, and the tinkling of a thousand little bells made a background to the harsh clangor of the gongs, the shrill trumpeting of the elephants, the yells of the mahouts and the thunderous roars of startled dragons. Some of these last flew forward in silence, but most of them protested to the full power of their lungs. Soon, thirty golden bodies lay stretched on the grass behind the bowmen; and, of these victims, six had fallen to English archery. Cleodolinda had five to her credit, not counting the one she had shared with Walter. The King missed unfailingly, but this did not seem to affect his enjoyment in the least. He was at the end of the line, and a little crowd of peasants had collected there. They shouted respectful but contradictory advice . . . “Too far forward, your Majesty” . . . “Too far behind!” He tried to take it all.

The elephant line was approaching the edge of the wood, and the din had become deafening. Then, suddenly, there came a change in the uproar. The trumpeting of the elephants increased; but the bells stopped ringing, the gongs ceased to beat, and, in place of yells of encouragement, shouts of warning were hurled to and fro along the evidently halted line. . . . “What’s that?” . . . “Look out, Abdullah!” . . . “There it goes!” . . . “Mind! Hamid, mind! It’s in front of you!” . . . “Danger! Danger!” The dragons had become completely silent.

Читать дальше