‘He got down it. I remember.’

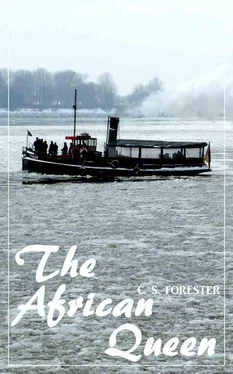

‘Yerss, miss. In a dugout canoe. ’E ’ad half a dozen Swahili paddlers. Map making, ’e was. There’s places where this ’ole river isn’t more than twenty yards wide, an’ the water goes shooting down there like—like out of a tap, miss. Canoe might be all right there, but we couldn’t never get this ole launch through.’

‘Then how did the launch get here, in the first place?’

‘By rile, miss, I suppose, like all the other ’eavy stuff. ’Spect they sent ’er up to Limbasi from the coast in sections, and put ’er together on the bank. Why, they carried the Louisa to the Lake, by ’and, miss.’

‘Yes, I remember.’

Samuel had nearly got himself expelled from the colony because of the vehement protests he had made on behalf of the natives on that occasion. Now her brother was dead, and he had been the best man on earth.

Rose had been accustomed all her life to follow the guidance of another—her father, her mother, or her brother. She had stood stoutly by her brother’s side during his endless bickerings with the German authorities. She had been his appreciative if uncomprehending audience when he had seen fit to discuss doctrine with her. For his sake she had slaved—rather ineffectively—to learn Swahili, and German, and the other languages, thereby suffering her share of the punishment which mankind had to bear (so Samuel assured her) for the sin committed at Babel. She would have been horrified if anyone had told her that if her brother had elected to be a Papist or an infidel she would have been the same, but it was perfectly true. Rose came of a stratum of society and of history in which woman adhered to her menfolk’s opinions. She was thinking for herself now for the first time in her life, if exception be made of housekeeping problems.

It was not easy, this forming of her own judgements; especially when it involved making an estimate of a man’s character and veracity. She stared fixedly at Allnutt’s face, through the cloud of flies that hovered round it, and Allnutt, conscious of her scrutiny, fidgeted uncomfortably. Resolve was hardening in Rose’s heart.

Ten years ago she had come out here, sailing with her brother in the cheap and nasty Italian cargo boat in which the Argyll Society had secured passages for them. The first officer of that ship had been an ingratiating Italian, and not even Rose’s frozen spinsterhood had sufficed to keep him away. Her figure at twenty-three had displayed the promise which now at thirty-three it had fulfilled. The first officer had been unable to keep his eyes from its solid curves, and she was the only woman on board—in fact, for long intervals she was the only woman within a hundred miles—and he could no more stop himself from wooing her than he could stop breathing. He was the sort of man who would make love to a brass idol if nothing better presented itself.

It was a queer wooing, and one which had never progressed even as far as a hand-clasp—Rose had not even known that she was being made up to. But one of the manoeuvres which the Italian had adopted with which to ingratiate himself had been ingenious. At Gibraltar, at Malta, at Alexandria, at Port Said, he had spoken eloquently, in his fascinating broken English, about the far-flung British Empire, and he had called her attention to the big ships, grimly beautiful, and the White Ensign fluttering at the stern, and he had spoken of it as the flag upon which the sun never sets. It had been a subtle method of flattery, and one deserving of more success than the unfortunate Italian actually achieved.

It had caught Rose’s imagination for the moment, the sight of the rigid line of the Mediterranean squadron battling its way into Valetta harbour through the high steep seas of a Levanter with the red-crossed Admiral’s flag in the van, and the thought of the wide Empire that squadron guarded, and all the glamour and romance of Imperial dominion.

For ten years those thoughts had been suppressed out of loyalty to her brother, who was a man of peace, and saw no beauty in Empire, nor object in spending money on battleships while there remained poor to be fed and heathen to be converted. Now, with her brother dead, the thoughts surged up once more. The war he had said would never come had come at last, and had killed him with its coming. The Empire was in danger. As Rose sat sweating in the sternsheets of the African Queen she felt within her a boiling flood of patriotism. Her hands clasped and unclasped; there was a flush of pink showing through the sallow sunburn of her cheeks.

Restlessly, she rose from her seat and went forward, sidling past the engine, to where the stores were heaped up gunwale-high in the bows—all the miscellany of stuff comprised in the regular fortnight’s consignment to the half a dozen white men at the Belgian mine. She looked at it for inspiration, just as she had looked at the contents of the larder for inspiration when confronted with a housekeeping problem. Allnutt came and stood beside her.

‘What are those boxes with the red lines on them?’ she demanded.

‘That’s the blasting gelatine I told you about, miss.’

‘Isn’t it dangerous?’

‘Coo, bless you, miss, no.’ Allnutt was glad of the opportunity of displaying his indifference in the presence of this woman who was growing peremptory and uppish. ‘This is safety stuff, this is. It’s quite ’appy in its cases ’ere. You can let it get wet an’ it doesn’t do no ’arm. If you set fire to it it just burns. You can ’it it wiv a ’ammer an’ it won’t go off—at least, I don’t fink it will. What you mustn’t do is to bang off detonators, gunpowder, like, or cartridges, into it. But we won’t be doing that, miss. I’ll put it over the side if it worries you, though.’

‘No!’ said Rose, sharply. ‘We may want it.’

Even if there were no bridges to blow up, there ought to be a satisfactory employment to be found in wartime for a couple of hundredweight of explosive—and lingering in Rose’s mind there were still the beginnings of a plan, even though it was a vague plan, and despite Allnutt’s decisive statement that the descent of the river was impossible.

In the very bottom of the boat, half covered with boxes, lay two large iron tubes, rounded at one end, conical at the other, and in the conical ends were brass fittings—taps and pressure gauges.

‘What are those?’ asked Rose.

‘They’re the cylinders of oxygen and hydrogen. We couldn’t find no use for them, miss, not anyhow. First time we shift cargo I’ll drop ’em over.’

‘No, I shouldn’t do that,’ said Rose. All sorts of incredibly vague memories were stirring in her mind. She looked at the long black cylinders again.

‘They look like—like torpedoes,’ she said at length, musingly, and with the words her plan began to develop apace. She turned upon the Cockney mechanic.

‘Allnutt,’ she demanded. ‘Could you make a torpedo?’

Allnutt smiled pityingly at that.

‘Could I mike a torpedo?’ he said. ‘Could I mike—? Arst me to build you a dreadnought and do the thing in style. You don’t really know what you’re saying, miss. It’s this way, you see, miss. A torpedo—’

Allnutt’s little lecture on the nature of torpedoes was in the main correct, and his estimate of his incapacity to make one was absolutely correct. Torpedoes are representative of the last refinements of human ingenuity. They cost at least a thousand pounds apiece. The inventive power of a large body of men, picked under a rigorous system of selection, has been devoted for thirty years to perfecting this method of destroying what thousands of other inventors have helped to construct. To make a torpedo capable of running true, in a straight line and at a uniform depth, as Allnutt pointed out, would call for a workshop full of skilled mechanics, supplied with accurate tools, and working under the direction of a specialist on the subject. No one could expect Allnutt working by himself in the heart of the African forest with only the African Queen’s repair outfit to achieve even the veriest botch of an attempt at it. Allnutt fairly let himself go on the allied subjects of gyroscopes, and compressed air chambers, and vertical rudders, and horizontal rudders, and compensating weights. He fairly spouted technicalities. Not even the Cockney spirit of enterprise with its willingness to try anything once, which was still alive somewhere deep in Allnutt’s interior, could induce him to make the slightest effort at constructing a locomotive torpedo.

Читать дальше