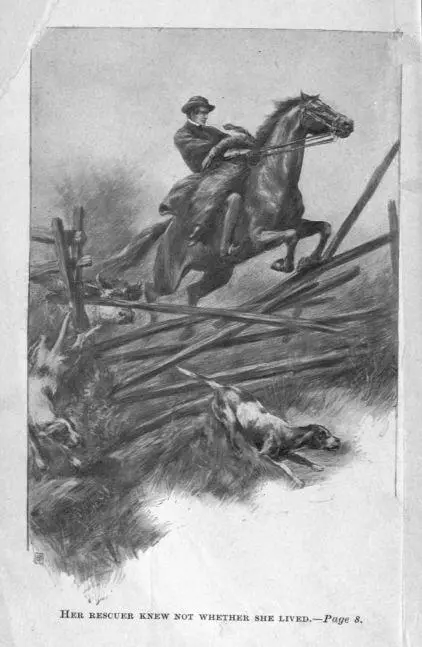

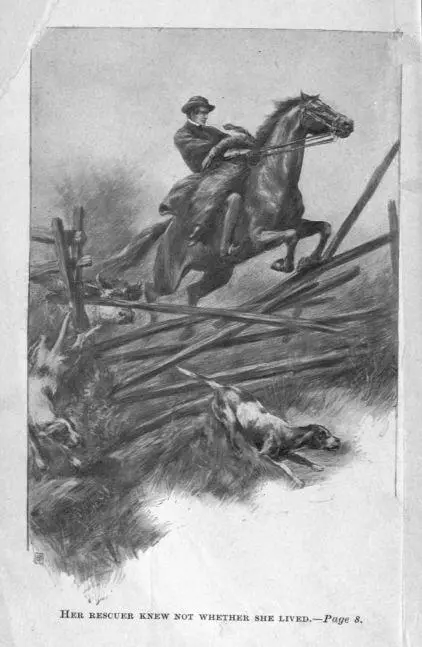

As he did so his rider saw to his horror that the young woman's mount had faltered in her frightened flight, and in the next instant the beautiful mare was lifted bodily from the ground, impaled upon the sharp horns of the bull and evidently done to death by the goring. As the animal fell the young woman was hurled forward half a dozen yards, and before the wrath-blinded bull could gather himself together for a charge upon her prostrate form, Boyd Westover forced his own horse between the bull and his victim and with three or four rapid swishes of the cruel black-snake whip across the animal's face and eyes, sent him staggering back.

The delay, as the young man knew, would be but for a few seconds, but these proved sufficient for his purpose. Turning his horse toward the unconscious girl, he hooked his left knee around the cantle of his saddle and, hanging almost head downwards, seized her about the waist. Recovering his position, he placed her across the horse's withers. The bull was almost upon him now, but a sharp touch of the spurs caused the horse to spring forward at a full run in time to save himself and his riders, though the escape was so narrow that one of the bull's horns tore an ugly gash in the calf of Boyd Westover's leg.

The body of the girl hung limp across the withers, so that her rescuer knew not whether she lived or had been killed by her fall. Until his horse cleared the fence again—this time scattering the upper rails as he did so—there was no time for inquiry. But once out of the field, the young man reined in the frantic creature, and lifting the girl's head to his shoulder, felt her fluttering breath upon his cheek.

"Thank God she lives!" he exclaimed with reverent fervor, but his efforts to rouse her to consciousness were unavailing.

"It may be only a faint," he thought, but such fainting as he had seen among women had been far less enduring than this, and the memory of that fact greatly alarmed him.

He reflected that in any case the shock produced by the dashing of water into the face is desirable at such times, and turning his horse's head he rode down a slope into a shaded, grass-carpeted dell, where a bubbling spring arose. Gently laying the girl on the greensward, but resting her head in his lap, he dashed handfuls of water into her face, with the result of arousing her almost at once. When she opened her eyes they were vacant and dreamy, like those of one only half awakened from sleep, but a few moments later the light came back into them, and she spoke.

"Is it you, Boyd? Then you're not dead, as I dreamed you were."

"Oh, no, I'm not hurt," he replied—ignoring his lacerated leg—"but you mustn't talk yet. Lie still till you feel better." And with that he gently passed his hand over her eyes, closing them.

She lay quiet for a minute or two seemingly asleep, and he, moved by a sudden impulse—whether of passion or pity he knew not—bent over and pressed his lips to hers—gently uttering her name—"Margaret."

Instantly he repented, as she opened her eyes and with a flushing face tried to raise herself to a sitting posture, saying as she made the effort.

"I reckon you mustn't do that."

But the effort to rise was futile. Sharp pain caused her to grow pale again and she sank back as she had been.

"Where are you hurt, Margaret?" Boyd asked in sympathetic distress.

"I don't know; all over I reckon."

"Are any of your bones broken? Feel of them and see."

"I reckon not. I can't tell. The pains are all over me—mostly inside. I reckon I'm going to faint."

Boyd Westover was now seriously alarmed. He vaguely remembered hearing of persons dying of "internal injuries," though externally showing no hurt. Instantly he lifted the girl again and, mounting with her in his arms, set off at a gallop toward the great house at Wanalah.

The sharp prick of a pin, as he adjusted his burden on the withers, attracted his attention to the two flaming red bandana kerchiefs, pinned by their corners to Margaret's shoulders, and in the midst of his apprehensions for her life he found time to wonder why she had decorated herself in that extraordinary way. He was too full of anxious concern to question her on so trivial a matter, but she, recovering herself, volunteered an explanation, after asking him to reduce the horse's gait to a walk.

"I reckon I was right foolish," she said, laughing in spite of her pain. "You see this is one of old Aunt Sally's birthdays. She has one every three or four months now, and she's rapidly adding to her ninety years—a year at each birthday. She was my Mammy you know, and so I always take her a present on her birthdays."

The girl paused in her speech as some sharp twinge of pain changed her smile into a grimace. It was only for a moment, and she continued:

"On her last birthday, two or three months ago, she told me I would some day be an angel with red wings, and so when I set out this morning to take her these two turban kerchiefs, the foolish whim came to me to pin them to my shoulders and make red wings of them."

Again an access of severe pain silenced speech and she closed her eyes while her lips grew pale. Evidently the effort to chatter had been too much for her, and Boyd rightly guessed that she had been forcing herself to talk of her little prank by way of preventing him from saying more serious things which she did not wish just then to hear.

He in his turn resolved to say those more serious things at the earliest opportunity. He felt that in caressing her as he had done, down there by the spring, he had placed himself under a binding obligation to explain at the first possible opportunity, and the explanation could take but one form—a full and free declaration of his yet unspoken passion. This, he felt, he had no right to delay one moment longer than he must, but as she lay still with closed eyes, her head upon his shoulder and his arm about her, he realized that his present and very pressing task was to place her as soon as possible in the tender care of his mother and her maids.

The rest must wait.

CHAPTER II – A SONG WITHOUT WORDS

The physician for whom Boyd Westover sent a young negro at breakneck speed, while his mother's maids were getting Margaret Conway to bed, reported that she had "sustained painful contusions" and was additionally "suffering from shock," but that no bones were broken and, so far as he could determine, no serious internal injuries had befallen. He directed that she should remain in bed for a few days, and then stay quietly at Wanalah, without attempting a homeward journey until he should himself give permission.

"Above all," he said to Boyd, "she must not be excited in any way—pleasurably or the reverse—lest hysteria supervene."

Boyd smiled a little over the medical man's stilted diction, and rejoiced in the assurance of Margaret's safety which the ponderous phraseology gave him. But upon reflection he chafed a good deal over the restraint the doctor's instructions required him to put upon himself. He was impatient now to put into words the declaration of love which his caresses had implied and promised. He was still more impatient for her reply to that declaration, for, like the modest young lover that he was, he gravely feared his fate and was annoyed by the necessity of waiting before putting it to the test.

Her words, spoken half consciously when she had received or repelled his embraces—for he could not determine in his own mind whether she had meant to do the one or the other—in no wise encouraged his self-confidence. He recalled those words:—"I reckon you mustn't do that"—and questioned them closely as to their significance, but no satisfactory answer came. The utterance might mean anything or nothing. And what did the suddenly flushing face that accompanied it suggest? Was it joy or sorrow, pleasure or resentment that had sent the blood to her cheeks in that way, and prompted her attempt to escape him by rising? Wonder as he might he could not tell, and as he paced the colonnaded porch that night after all the house was asleep, he succeeded only in working himself into a passionate fury of impatience and maddening perplexity.

Читать дальше