The petrochemical and plastics industries, like many modern capitalist industries, grew out of war. Yet there is an even darker side to this origin story. In the interwar period, the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben, one of the main players in the polymer science revolution, led an international cartel of corporations that restricted global trade in synthetic oil and rubber. During the Second World War, IG Farben operated a concentration camp using slave labour on one of its industrial sites, conducted medical experiments on prisoners, and supplied the toxic gas Zyklon B to the concentration camps. 46In 1941, the United States conducted an anti-trust investigation into Standard Oil (now Exxon) and its six subsidiaries for conspiring with IG Farben to restrict trade, indicting three corporate leaders, who resigned. 47Twenty-three of IG Farben’s directors were tried by the US Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg between 1947 and 1949 for war crimes and crimes against humanity, thirteen of whom were convicted. This was a hallmark international case for holding business leaders responsible for corporate crimes. 48

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the petrochemical cartels dissolved. In 1951, IG Farben was broken up into different companies, including BASF, Bayer, and Hoechst, which each gained their own legal identities. However, tacit cooperation continued between the leading American and European petrochemical companies. 49This laid the historical foundations of industrial collaboration and collusion that continued in the toxic scandals of later years. The exponential growth of plastics in the post-war period was not an inevitable outcome of material innovation, as it is often framed, but a legacy of war.

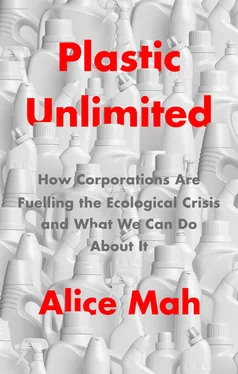

The European plastics industry celebrated ‘100 Years of Plastics’ in December 2020 with the launch of a website about how plastics make life better and more sustainable. The tagline: ‘Unlimited Possibilities for the Future’. 50The hallmark achievement in 1920 was the publication of a ground-breaking research article by the German scientist and Nobel Prize winner Hermann Staudinger, which formed the basis for modern polymer science. A collaboration between the Macromolecular Chemistry Division of the Association of German Chemists and Plastics Europe Deutschland (the German branch of the Plastics Europe industry association), the website features monthly articles that showcase ways that plastics help society. The first article, ‘Plastics During the Pandemic’, singles out five plastics applications as making material contributions to COVID-19: protective clothing; plastics machinery (for making masks and other equipment); protective walls (transparent partition walls); medical sector materials; and the transport of vaccines (in insulated frozen boxes). 51Notably absent from this list are plastic bags and disposable food and beverage containers, which the industry had so actively promoted as the ‘sanitary choice’ at the beginning of the pandemic. 52Despite its centennial theme, the ‘100 Years of Plastic’ website avoids any mention of the wartime origins of modern plastics. Instead of reflecting on the past, it speculates on the future, using the occasion to capture the celebratory mood of the plastics revival of the pandemic. The unlimited possibilities for the future of plastics, naturally, are all about perpetual growth.

The capitalist pursuit of unlimited growth is the key problem underlying the plastics crisis. It is not unique to the plastics industry, but rather the defining feature of all corporations within modern capitalism. Publicly traded corporations are legally obliged to act in the ‘best interests’ of shareholders, which most people interpret to mean maximizing profits and growth. However, as anti-trust lawyer Michelle Meagher argues, the powerful norm of shareholder value exists only weakly in law and is unenforceable. In other words, according to Meagher: ‘Shareholder value is not the law – or it does not have to be, if we collectively agree that it is not.’ 53Meagher notes that when corporations were first created in England in the seventeenth century to fund public projects, ‘the norm of accountability was not limited liability but actually unlimited liability’, as their principal obligation was to fulfil their public purpose. Of course, Meagher reminds us, the ‘public’ purpose that these early corporations served was tied to the colonial ambitions of the British Empire, but her point is that the norms governing corporations can change. The limited liability of the modern corporation, in her view, ‘removes responsibility and accountability’. 54

Recently, business leaders have attempted to cast the corporation’s shareholder purpose in a new light. In April 2019, the Business Roundtable of more than 200 of the world’s top CEOs proclaimed that the new purpose of publicly traded corporations would be to serve the interests not only of shareholders but also of workers, communities, and the environment. 55This exemplifies what law professor Joel Bakan describes as the ‘new’ corporation of the twenty-first century: ‘doing well by doing good’, or ‘making money through social and environmental values rather than in spite of them’. 56The problem, Bakan argues, is that the legal structure of corporations – enforced by the profit-seeking imperative of capitalism – requires that they will always prioritize doing well over doing good. Furthermore, as the political scientist Peter Dauvergne observes, the business case for corporate sustainability is not just about deflecting criticism; it is also about gaining corporate power over regulations. 57

Corporations Across the Plastics Value Chain

Often, critics of the plastics industry lump all plastics corporations together, using the term ‘Big Plastic’ to apply equally to oil, packaging, consumer goods, and beverage companies. 58For example, in September 2020, the Changing Markets Foundation published the report Talking Trash: The Corporate Playbook of False Solution s, which accused ‘Big Plastic’ of ‘two-faced hypocrisy’ for claiming to be committed to solutions to the plastics crisis, while obstructing and undermining legislative solutions to it. 59Although there are many similarities and collaborations between Big Plastic companies, however, there are also important differences. Corporations across the plastics value chain span a wide range of interconnected industries, from fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal) and biofuels (sugar and biomass), to petrochemicals (transforming hydrocarbons into plastic resins), plastics converters (converting plastic resins into packaging and other end uses), plastic end markets (e.g., food and beverage companies and other ‘fast-moving consumer goods’ or FMCG companies), and waste management and recycling.

One of the main differences between these industry segments is their relative size and power. Until recently, the majority of public attention has focused on the top plastics polluters at the downstream end of the sector, due to the high visibility of plastic packaging waste. In particular, many NGOs and activists have singled out big brands in the consumer goods and beverage industries (e.g., Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Coca-Cola, and Nestlé), which rely heavily on single-use plastic packaging. Increasingly, however, researchers and policymakers have shifted their attention upstream to the plastics producers in the petrochemical industry, with concerns about the industry’s anti-competitive practices, lack of transparency, toxic pollution, and continuing reliance on fossil fuels. 60A relatively small number of very large firms dominate the market through technological advantage and access to cheap feedstocks, creating strong barriers to entry with economies of scale and scope. 61The top plastics producers by annual turnover are vertically integrated oil and gas companies (e.g., ExxonMobil, Saudi Aramco, Chevron Philips) and multinational chemical companies (e.g., BASF, Dow, DuPont, INEOS), which operate thousands of production sites worldwide, clustered in massive petrochemical complexes next to oil refineries, pipelines, and ports. They also have the strongest voices within plastics industry trade associations such as the World Plastics Council, the Plastics Industry Association, Plastics Europe, the European Petrochemical Association, and the American Chemistry Council.

Читать дальше