One fascinating aspect of dominion slave studies is the examination of Jamaica’s, and the wider West Indian, role in the formation of British national, gender and familial identities by scholars of British cultural and imperial studies, especially Catherine Hall and her collaborators, 102Kathleen Wilson, 103Susan Amussen 104and Katie Donington. 105The last three works are of special value in their focus on the 17th and 18th centuries and transgenerational developments, taking temporality seriously in their historical analysis. An important and necessary dimension of these studies are those making the case for reparations in light of what is now acknowledged as a crime against humanity, most notably those of Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd. 106

The studies discussed above have all greatly enriched our knowledge of enslavement in Jamaica and the broader West Indies. However, the single most important development in the study of modern slavery in the Atlantic since the 1960s, with important implications for our understanding of Jamaican slave society, concerns the Atlantic slave trade. Important studies had been published on the trade from the early 1930s, 107with a surge in the late fifties and sixties, prompted in part by the Civil Rights movement in America and the rise in the study of African history with the post-war decolonization movements. I made full use of those earlier works in Chapter 5of The Sociology of Slavery , ‘The Tribal Origins of the Jamaican Slaves’. 108However, the publication of Curtin’s seminal work, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census , in 1972, 109marked a fundamental turning point in the study of the slave trade, and of Atlantic History more generally, bringing methodological rigour and synthetic integration to the subject that overturned long established views about the nature and extent of the trade. 110The most significant of his findings was the point estimate of the total number of slaves imported to the New World at 9,566,000, complete with a margin of error of between +9.8 and −16.4 per cent. This greatly reduced the guestimates that prevailed at the time, some as high as thirty million transported from Africa. Of special interest to me were Curtin’s estimates of the contribution of the different regions of Africa to the slave trade, the number and proportions of slaves who went to the different regions of the Americas, especially the Caribbean, and the numbers exported over time. Curtin’s work was based entirely on secondary sources, among which was The Sociology of Slavery . Indeed, one of the more important sections of the book, Chapter 5on the English slave trade in the 18th century, relied substantially on The Sociology of Slavery and LePage’s Jamaican Creole 111for its main conclusions on the cross tabulation of the changing ethnic origins of the captives through time. 112Curtin’s work stimulated a flood of studies, which continues to the present. A critical review of the work by Inikori not only pinpointed some of its main limitations but argued, correctly, that Curtin’s estimates were too low and required a ‘substantial upward revision’. 113

The next major turning point was the shift towards primary sources and more precise quantification by scholars such as David Eltis, David Richardson, Herbet S. Klein, Henry Gemery, Jan Hogendorn, John Thornton, J. E. Inikori, among many others. The third main development came with the Trans-Atlantic and Intra-Atlantic slave trade databases. This enormously valuable resource, called ‘the gold standard of digital humanities’, originating in earlier work by Herbert Klein, Jean Mettas, Serge and Michelle Daget and David Richardson, evolved into a single multisource dataset through the joint work of David Eltis, Stephen Behrendt and David Richardson, who received critical support in the formative stage of the project from Harvard’s W. E. B. DuBois Institute for Afro-American Research (and later the Harvard Hutchin’s Center), with later support from funding agencies and universities, especially Emory where it was located for twenty years after leaving Harvard, 114and now Rice University, to which it moved in 2021.

There are now 36,000 trans-Atlantic voyages in the database, each of which carried an average of 304 captives. One important correction emerging from the database concerns Curtin’s original estimate of 9.5 million Africans transported from Africa. The database indicates that Inikori was correct in his assessment that Curtin had substantially underestimated the extent of the trade: the most recent estimate, based on far better primary sources and careful quantification, is that at least 12,520,000 African captives were forced from Africa for the Americas, with a possible upper limit of 15.4 million enslaved, which means that there were between 24 and 62 per cent more enslaved Africans transported than Curtin’s point estimate. At the two extremes of these estimates – Curtin’s eight million and the current database’s 15.4 million – Curtin may have underestimated the traffic by nearly 100 per cent. Since new voyages are being added continuously to the database, the correction is likely to be higher. Staying with the database’s lower estimate, of the 12.5 million who left, 10.7 million disembarked mainly in the Americas, with an average of 265 Africans. Some 633 voyages (1.8%) were lost at sea or captured, or experienced some other fate, including slave revolts. 115

Curtin had already noted that a disproportionate number of slaves landed in the Caribbean. However, for students of West Indian enslavement, and for Jamaica in particular, the database indicates that, in both proportionate and absolute terms, the numbers going to Jamaica were staggering. The new map, from the project’s valuable set of Introductory Maps, 116visually indicates the extraordinary numbers that went to the Caribbean, especially Jamaica, when compared with North America. Having carefully followed the development of the database over the years, I have repeatedly drawn on it to update the estimated numbers going to Jamaica and the regions from which the Africans arriving in the island came.

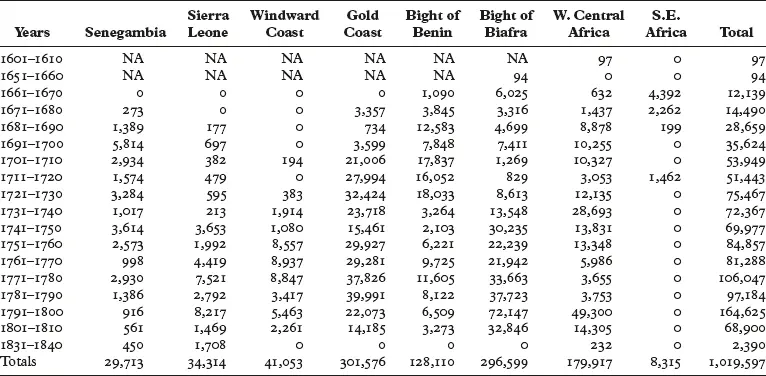

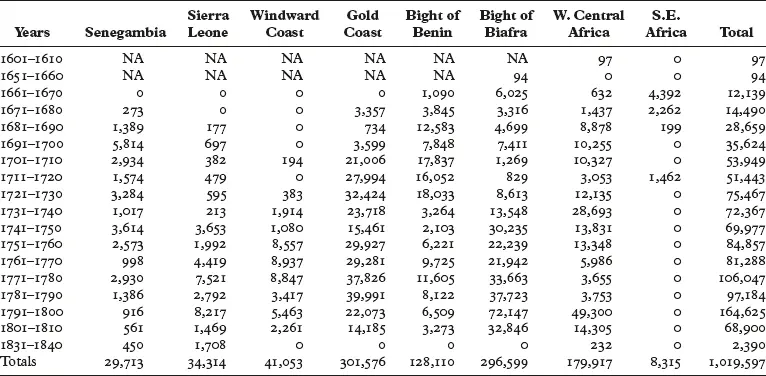

How do these recent figures compare with my estimates of over 55 years ago? In the first place, far more slaves went to Jamaica than any of us, including Curtin, suspected at the time. I was, however, more concerned with the proportion of slaves contributed by different regions of Africa, given my primary interest in tracing the tribal and cultural origins of the Jamaican enslaved, reflected in the title of Chapter 5. In this regard, apart from the very earliest period,1655–1700, my proportional estimates have held up reasonably well. In broad terms, I had estimated that during the first half of the period of slavery the single largest group of slaves would have come from what was called the Gold Coast (now Ghana), the second largest from the Slave Coast and the Bight of Benin (now Nigeria), and that during most of the second half of the eighteenth century the largest contingent came from Nigeria, but that ‘during the last seventeen years of the trade there was a striking reappearance of slaves from Southwestern Africa, particularly from the region of the Congo’ (p. 144). This is broadly what the Atlantic database shows, although the decennial estimates differed, especially during the 17th century.

Table 0. Number of Slaves Disembarked in Jamaica from Embarkation Regions of Africa, 1601–1840

Table composed by author from Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Data Base , https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates

One pleasant surprise is the degree to which slaves from Ghana dominated the period between 1700 and 1740. I had argued, along with the creole linguists, that this was the period in which the creole language and Afro-Jamaican culture was at its most formative stage and the major presence of slaves from Ghana during this time would have meant that their impact would remain lasting, even if their numbers were later surpassed by enslaved persons from Nigeria. This argument is now strengthened.

Читать дальше