Milburg Mansfield - The Automobilist Abroad

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Milburg Mansfield - The Automobilist Abroad» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Путешествия и география, foreign_prose, foreign_language, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Automobilist Abroad

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Automobilist Abroad: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Automobilist Abroad»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Automobilist Abroad — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Automobilist Abroad», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The arrangement and classification laid down by Philippe-Auguste have never been changed, simply modified and renamed; thus the Routes Royales – such as followed nearly a straight line from Paris by the right bank of the Loire to Amboise and to Nantes – became the Routes Nationales of to-day.

Soon wheeled traffic became a thing to be considered, and royal cortèges moved about the land with much the same freedom and stateliness of the state coaches which one sees to-day in pageants, as relics of a past monarchical splendour.

Louis XI. created the " Service des Postes " in France, which made new demands upon the now more numerous routes and roadways, and Louis XII., François I., Henri II., and Charles IX., all made numerous ordinances for the policing and maintenance of them.

Henri IV., and his minister Sully, built many more of these great lines of communication, and thus gave the first real and tangible aid to the commerce and agriculture of the kingdom. He was something of an aesthetic soul too, this Henri of Bearn, for he was the originator of the scheme to make the great roadways of France tree-shaded boulevards, which in truth is what many of them are to-day. This monarch of love, intrigues, religious reversion, and strange oaths passed the first (and only, for the present is simply a continuance thereof) ordonnance making the planting of trees along the national highroads compulsory on the local authorities.

Under Louis XIV., Colbert continued the good work and put up the first mile-stone, or whatever its equivalent was in that day, measuring from the Parvis de Notre Dame at Paris. Some of these Louis XIV. bornes , or stones, still exist, though they have, of course, been replaced throughout by kilometre stones.

The foregoing tells in brief of the natural development of the magnificent roads of France. Their history does not differ greatly from the development of the other great European lines of travel, across Northern Italy to Switzerland, down the Rhine valley and, branching into two forks, through Holland and through Belgium to the North Sea.

In England the main travel routes run north, east, south, and west from London as a radiating centre, and each took, in the later coaching days, such distinctive names as "The Portsmouth Road," "The Dover Road," "The Bath Road," and "The Great North Road." Their histories have been written in fascinating manner, so they are only referred to here.

It is in France, one may almost say, that automobile touring begins and ends, in that it is more practicable and enjoyable there; and so la belle France continually projects itself into one's horizon when viewing the subject of automobilism.

It may be that there are persons living to-day who regret the passing of the good old times when they travelled – most uncomfortably, be it remarked – by stage-coach and suffered all the inclemencies of bad weather en route without a word of protest but a genial grumble, which they sought to antidote by copious libations of anything liquid and strong. The automobile has changed all this. The traveller by automobile doesn't resort to alcoholic drinks to put, or keep, him in a good humour, and, when he sees a lumbering van or family cart making its way for many miles from one widely separated region to another, he accelerates his own motive power and leaves the good old ways of the good old days as far behind as he can, and recalls the words of Sidney Smith:

"The good of other times let others state,

I think it lucky I was born so late."

A certain picturesqueness of travel may be wanting when comparing the automobile with the whirling coach-and-four of other days, but there is vastly more comfort for all concerned, and no one will regret the march of progress when he considers that nothing but the means of transportation has been changed. The delightful prospects of hill and vale are still there, the long stretches of silent road and, in France and Germany, great forest routes which are as wild and unbroken, except for the magnificent surface of the roads, as they were when mediæval travelers startled the deer and wild boar. You may even do this to-day with an automobile in more than one forest tract of France, and that not far from the great centres of population either.

The invention of carriage-springs – the same which, with but little variation, we use on the automobile – by the wife of an apothecary in the Quartier de St. Antoine at Paris, in 1600, was the prime cause of the increased popularity of travel by road in France.

In 1776, the routes of France were divided into four categories:

1. Those leading from Paris to the principal interior cities and seaports.

2. Those communicating directly between the principal cities.

3. Those communicating directly between the cities and towns of one province and those of another.

4. Those serving the smaller towns and bourgs.

Those in the first class were to be 13.35 metres in width, the second 11.90, the third 10, the fourth 7.90. The road makers and menders of England and America could not get better models than these.

The advent of the automobile has brought a new factor into the matter of road making and mending, but certainly he would be an ignorant person indeed who would claim that the automobile does a tithe of the road damage that is done by horse-drawn traffic.

At a high rate of speed, however, the automobile does raise a fine sandy dust, and exposes the macadam. A French authority states that up to twenty to twenty-five kilometres an hour the automobile does little or no harm to the roads, but when they increase to over fifty kilometres an hour they do damage the surface somewhat. Just what the ultimate outcome of it will be remains to be seen, but France is unlikely to do anything which will work against the interests of the automobilist.

In consequence of this newer and faster mode of travelling, it is being found that on some parts of the roads the convexity of the surface is too great, and especially at curves, where fast motors frequently skid on the rounded surface. To obviate this a piece of road near the Croix d'Augas in the Orleannais has had the outer side of the curve raised eight centimetres above the centre of the road, in somewhat the same manner as on the curve of a railway. Since this innovation has proved highly successful and pleasing to the devotees of the new form of travel, it is likely to be further adopted.

In the early period of the construction of French roads the earth formation was made horizontal, but Trésaguet, a French engineer, introduced the rounded form, or camber, and this is the method now almost generally adopted, both in France and England. Only some 14,000 kilometres of the national routes have a hand-set foundation, the others being what are termed broken-stone roads – the stone used is broken in pieces and laid on promiscuously, after the system introduced by Macadam. Some of the second and third class, roads are constructed of gravel, and others, of earth.

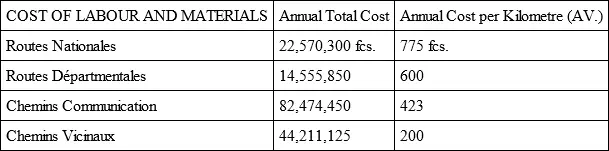

From the official report of 1893 it appears that the cost of maintenance of roads in France was as follows:

The above is for materials and labour on the roadways only, and something between 33 1/3 per cent, and 50 per cent. is added for the maintenance of watercourses and sidewalks, the planting of trees, and for general administrative expenses.

Excepting for twenty kilometres or so around Paris, the vehicular traffic on the country roads of France does not seem to be in any way excessive. The style of vehicles in France that carry into the cities farm and garden produce, wood, stone, etc., are large wagons with wheels six to seven feet in diameter. These wagons are more easily hauled and naturally do less damage to the roads than narrow-tired, low-wheeled trucks or drays. The horses in Paris, and in the country, are nearly all plain shod, with no heels or toes to act like a pick to break up the surface. Sometimes even one sees draught-horses with great flat, iron shoes extending out beyond the hoof in all directions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Automobilist Abroad»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Automobilist Abroad» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Automobilist Abroad» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.