“Impossible,” he then says.

“Impossible? In Mashhad or in all of Iran?”

“In the whole country. But you could go to another office and talk to the people there.”

“Do you think it’s worth it?”

“If you ask me, no chance. Big problem.”

“And at the police station?”

“No, they can’t speak English. I’ll write down the address of another visa office.”

“And they will understand me?”

“Yes, but it’s still absolutely inconceivable that you will get an extension to your visa.”

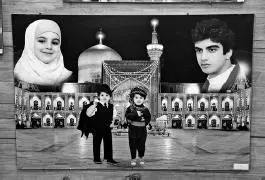

Back on the street I hold the paper with the address under a cab driver’s nose. After twenty minutes he stops outside a green wall in a side street off Piruzi Boulevard. “Edareh-ye Gozarnameh,” he says, the name of the office that the man in the travel agency gave me. A narrow entrance leads to a courtyard with wood-paneled reception huts, and a couple armed soldiers walk around busily. The counter clerk greets me with a radiant smile.

“Hello, where do you come from?” he asks.

“Germany.”

“Ooh, Germany! Welcome to Mashhad! You probably want your visa extended. Please go into the main building, turn left, and speak to my friend!” I am so surprised by the friendly reception that I almost drop my passport.

The “friend” in the next room carries on where the other left off.

“How are you?”

“Fine, thanks.”

What can I do for you?”

“I’d like to extend my visa.”

“Okay, fill out this form. How long is your visa valid?”

“Another five days.”

“Okay.”

“How long will the formalities take?”

“Roughly five days.”

“Oh, I’m traveling on tomorrow. Is there not a possibility of speeding things up?”

“Maybe. Maybe not.”

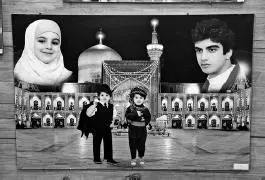

The warmth of the official is in stark contrast to the austere waiting room ambience of his office. Please don’t ask unnecessary questions to save the time of the staff and other customers is written on a poster. Another shows a portrait of Ayatollah Khamenei with the words: If the leader order, we attack. If want our head, we grant our head . A third poster is all about information for foreigners wanting to marry Iranian women: Please respect the valid laws, otherwise expect prison sentences from one to three years.

I fill out the form. German address, name of father, reason for travel (tourism), profession (website editor), Hotel (Al-Naby. It was the first hotel listed in Lonely Planet ). I give the piece of paper to a third official in a neighboring room, where a glass pane, with a tiny slit to pass the forms through, separates the applicant from the clerks. Above it there is an LED display with the calling numbers .167. 199. 267. A loud ping accompanies each new illuminated number.

“Is it possible to have it dealt with today?” I ask.

“I will check.” Two minutes later: “It could be possible, particularly as you are German. We like the Germans.” A slim man in military uniform, he glances at my application. “What a coincidence; I’m also a website editor. Which programming language do you use?”

“I write the content; I don’t program.” Now it’s getting tricky.

“Who do you work for?”

“I’m freelance and do advertising. For museums and cultural institutions.” He seems satisfied.

“Are you single?” is his next question.

“Yes,” I answer, too nervous about my Münchhausen job description to find the question adequately disconcerting.

“Excuse me, this isn’t an official question, but how tall are you?”

“6”2’.”

“Exactly as tall as me! We have a lot in common! How much do you earn a month?” So much for Please avoid unnecessary questions.

A fourth official joins us. Obviously, I’m the high point of an otherwise uneventful day.

“Hamburg! Mahdavikia!” he says.

“Ali Daei! Ali Karimi!” I respond. Party mood at the visa office. If it goes on like this, we will all become Facebook friends and meet up later for a couple beers. But back to business. A colleague returns with my application. “We have to translate it into Persian. Could you fill in the hotel address.” I copy the address from the guidebook in capital letters. Molla Hashem Lane, not far from the shrine. Imam Reza, please extend my visa. “Take a seat. You will be called.”

A number of different things go through your head while waiting in an Iranian government agency after having told a few half-truths. Hopefully they don’t call my phony hotel. Why didn’t I just say I was a student instead of a website editor, like Yasmin did at the police station in Kurdistan? What do I tell them if they google my name and discover that I work for a large news site and not for a little museum? So many questions. At least one of the other posters gives me some hope: Patience is the key to success and prosperity comes to those who wait.

Time and again I hear the thump of stamps, but none of them on my passport.

“Mr. Stephan,” is suddenly announced. I go to the counter, to an official I haven’t yet seen. The bucket seat is fixed at ninety degrees to the window so that it isn’t too comfortable.

The man looks at me with a serious face and says: “Hmm.” Pause. My passport is in his right hand. “We have a problem,” he continues.

Stay cool, don’t forget to breathe, look unsuspicious. “What kind of problem?” I ask.

“You were in Kerman and extended your visa there. We have to investigate that more thoroughly. You can come again on Wednesday.” That is in three days.

“But I have a bus ticket for tomorrow.”

“Hmm. Take a seat.”

Patience is the key to success. Patience is the key to success. Patience. In Lonely Planet I read: “Mashhad is not the best place to extend visas.” I sit there for 1 hour, 1.5 hours.

Thumping stamps, blinking three-digit numbers, groggy brain. Ping , 188. If the leader orders, we attack. Ping , 211. Mahdavikia. Ping , 286. Are you single? Ping , 189. We like Germans. Ping , 212. In Kerman they smoke opium so that plane passengers in the air overhead can get high. Ping , 190. Patience is the key to success.

“Mr. Stephan!” I almost miss hearing my name. I go to the counter. The 6”2’ website editor passes me my passport—with a stamp valid until May 28, 2014, four extra weeks. “Please sign here. Goodbye!”

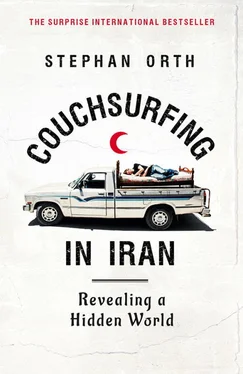

GREEN, WHITE, RED

THE LONG-DISTANCE BUSedges through the traffic jam on the outskirts of the city, where hundreds of Iranian flags and green, white, and red lights decorate the fringe of the highway. Three colors: green for belief, red for the blood of martyrs, and wedged in between, white for peace and friendship. A sword emblem with four crescent moons, stylized representations of the name of God, are emblazoned on the white background, as if to show that, when in doubt, weapons and Allah are more important than peace. But what kind of country is it really, over which this flag flies?

For me it is a country that enchants and enrages me at the same time. It enchants because there are such magical places, like Yazd, Shiraz, or Isfahan, and the countryside is magnificent, and because the warmth of the people is unique in the world. It enrages me because a state religion is imposed on the people without giving them a free choice. Because there are not enough opportunities for the young to make something of their lives. Because it is a rich country with gigantic oil and gas reserves, but most people have not benefited from them. They are like Cassim in the cave of treasures in Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves , surrounded by riches but trapped.

Читать дальше

![Stephan Orth - Behind Putin's Curtain - Friendships and Misadventures Inside Russia [aka Couchsurfing in Russia]](/books/415210/stephan-orth-behind-putin-s-curtain-friendships-a-thumb.webp)