George Herbert Betts - The Mind and Its Education

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «George Herbert Betts - The Mind and Its Education» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_edu, pedagogy_book, foreign_psychology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Mind and Its Education

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Mind and Its Education: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Mind and Its Education»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Mind and Its Education — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Mind and Its Education», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Learning to Interpret Expression.—If I would understand the workings of your mind I must therefore learn to read the language of physical expression. I must study human nature and learn to observe others. I must apply the information found in the texts to an interpretation of those about me. This study of others may be uncritical , as in the mere intelligent observation of those I meet; or it may be scientific , as when I conduct carefully planned psychological experiments. But in either case it consists in judging the inner states of consciousness by their physical manifestations.

The three methods by which mind may be studied are, then: (1) text-book description and explanation ; (2) introspection of my own conscious processes; and (3) observation of others, either uncritical or scientific.

2. THE NATURE OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Inner Nature of the Mind Not Revealed by Introspection.—We are not to be too greatly discouraged if, even by introspection, we cannot discover exactly what the mind is. No one knows what electricity is, though nearly everyone uses it in one form or another. We study the dynamo, the motor, and the conductors through which electricity manifests itself. We observe its effects in light, heat, and mechanical power, and so learn the laws which govern its operations. But we are almost as far from understanding its true nature as were the ancients who knew nothing of its uses. The dynamo does not create the electricity, but only furnishes the conditions which make it possible for electricity to manifest itself in doing the world's work. Likewise the brain or nervous system does not create the mind, but it furnishes the machine through which the mind works. We may study the nervous system and learn something of the conditions and limitations under which the mind operates, but this is not studying the mind itself. As in the case of electricity, what we know about the mind we must learn through the activities in which it manifests itself—these we can know, for they are in the experience of all. It is, then, only by studying these processes of consciousness that we come to know the laws which govern the mind and its development. What it is that thinks and feels and wills in us is too hard a problem for us here—indeed, has been too hard a problem for the philosophers through the ages. But the thinking and feeling and willing we can watch as they occur, and hence come to know.

Consciousness as a Process or Stream.—In looking in upon the mind we must expect to discover, then, not a thing , but a process . The thing forever eludes us, but the process is always present. Consciousness is like a stream, which, so far as we are concerned with it in a psychological discussion, has its rise at the cradle and its end at the grave. It begins with the babe's first faint gropings after light in his new world as he enters it, and ends with the man's last blind gropings after light in his old world as he leaves it. The stream is very narrow at first, only as wide as the few sensations which come to the babe when it sees the light or hears the sound; it grows wider as the mind develops, and is at last measured by the grand sum total of life's experience.

This mental stream is irresistible. No power outside of us can stop it while life lasts. We cannot stop it ourselves. When we try to stop thinking, the stream but changes its direction and flows on. While we wake and while we sleep, while we are unconscious under an anæsthetic, even, some sort of mental process continues. Sometimes the stream flows slowly, and our thoughts lag—we "feel slow"; again the stream flows faster, and we are lively and our thoughts come with a rush; or a fever seizes us and delirium comes on; then the stream runs wildly onward, defying our control, and a mad jargon of thoughts takes the place of our usual orderly array. In different persons, also, the mental stream moves at different rates, some minds being naturally slow-moving and some naturally quick in their operations.

Consciousness resembles a stream also in other particulars. A stream is an unbroken whole from its source to its mouth, and an observer stationed at one point cannot see all of it at once. He sees but the one little section which happens to be passing his station point at the time. The current may look much the same from moment to moment, but the component particles which constitute the stream are constantly changing. So it is with our thought. Its stream is continuous from birth till death, but we cannot see any considerable portion of it at one time. When we turn about quickly and look in upon our minds, we see but the little present moment. That of a few seconds ago is gone and will never return. The thought which occupied us a moment since can no more be recalled, just as it was, than can the particles composing a stream be re-collected and made to pass a given point in its course in precisely the same order and relation to one another as before. This means, then, that we can never have precisely the same mental state twice; that the thought of the moment cannot have the same associates that it had the first time; that the thought of this moment will never be ours again; that all we can know of our minds at any one time is the part of the process present in consciousness at that moment.

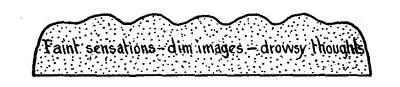

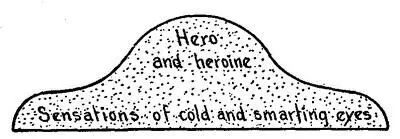

The Wave in the Stream of Consciousness.—The surface of our mental stream is not level, but is broken by a wave which stands above the rest; which is but another way of saying that some one thing is always more prominent in our thought than the rest. Only when we are in a sleepy reverie, or not thinking about much of anything, does the stream approximate a level. At all other times some one object occupies the highest point in our thought, to the more or less complete exclusion of other things which we might think about. A thousand and one objects are possible to our thought at any moment, but all except one thing occupy a secondary place, or are not present to our consciousness at all. They exist on the margin, or else are clear off the edge of consciousness, while the one thing occupies the center. We may be reading a fascinating book late at night in a cold room. The charm of the writer, the beauty of the heroine, or the bravery of the hero so occupies the mind that the weary eyes and chattering teeth are unnoticed. Consciousness has piled up in a high wave on the points of interest in the book, and the bodily sensations are for the moment on a much lower level. But let the book grow dull for a moment, and the make-up of the stream changes in a flash. Hero, heroine, or literary style no longer occupies the wave. They forfeit their place, the wave is taken by the bodily sensations, and we are conscious of the smarting eyes and shivering body, while these in turn give way to the next object which occupies the wave. Figs. 1-3 illustrate these changes.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Consciousness Likened to a Field.—The consciousness of any moment has been less happily likened to a field, in the center of which there is an elevation higher than the surrounding level. This center is where consciousness is piled up on the object which is for the moment foremost in our thought. The other objects of our consciousness are on the margin of the field for the time being, but any of them may the next moment claim the center and drive the former object to the margin, or it may drop entirely out of consciousness. This moment a noble resolve may occupy the center of the field, while a troublesome tooth begets sensations of discomfort which linger dimly on the outskirts of our consciousness; but a shooting pain from the tooth or a random thought crossing the mind, and lo! the tooth holds sway, and the resolve dimly fades to the margin of our consciousness and is gone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Mind and Its Education»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Mind and Its Education» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Mind and Its Education» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Edward Ellis - Adrift on the Pacific - A Boys [sic] Story of the Sea and its Perils](/books/753342/edward-ellis-adrift-on-the-pacific-a-boys-sic-s-thumb.webp)