I wish I could remember the letter better. He wanted to know why God had created so many people. Too many people, all cruel and unthinking and mean. He had specific complaints about various people, all addressed to God. Why did you create Freddie Hutchins? he asked. That son-of-a-gun treated me so bad, took away the only girl I ever loved. Or if you had to create him, why did you have to station him on Hooley Island? Why not put him over there on Guam? Or if he had to be on Hooley Island, how come you let me meet Tina in the first place? Why not just leave me alone? I never would have missed her, if you hadn’t made me meet her. And Colonel Gault. Why did you create that so-and-so? Or if you had to create him, how come you made him so mean? Or if he had to be mean, why not make him a private and me the colonel? And God, how come you let my mum run away with Bill Hastings, that son-of-a-gun who never did anything but drink and “God damn” this and “God damn” that? And what about me, who never took Your name in vain in my life? What about me? Why haven’t you done anything for me? What kind of a God are you that you treat those who love you like this? And look at what a mess the world is. If you didn’t do it, who did?

I mean, this guy was just a poor, ignorant simpleton from Franklin’s Pond Harbor, Maine, who didn’t understand the world at all. Didn’t have a clue.

It was very weird. And then at the end of the letter, he said he was coming up there. He was coming. He wanted some answers. I mean, it took a second for us to figure out what the hell he was talking about. Whew. That’s when we realized it wasn’t just a letter. It was a suicide note. Tundish had written it right there, and put it under the fireplace. And then he just walked into the ocean.

My father was reading the letter out loud. And when he finished, his voice was cracking, and I saw his hands were shaking. I mean shaking . And he put the letter down and the look on his face was awful... It scared the shit out of me. I’d never seen him so frightened. So he got all gruff and stuffed the letter in his pocket and said he’d give it to the local historical society. I think he probably just threw it away. No one ever said a word about it again.

In his book my father fudged that whole issue — like so many others — by saying the letter was illegible. That was my father’s way. If something was unpleasant or difficult, his way of dealing with it was simply not to deal with it. To bury himself in work, or pretend it never happened.

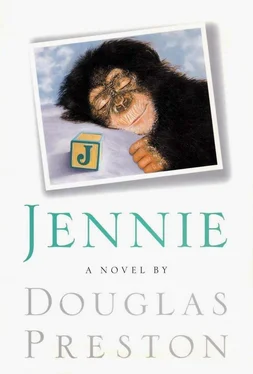

Oh, I’ll tell you, there’s a lot that isn’t in that book of his. A lot. And I’ll tell you something else. There’s a lot that isn’t going to be in your book either. You can no more understand and tell the truth about Jennie than that guy from Esquire . No offense. Even if we did tell you everything. Which we won’t. Nobody ever tells the full truth.

Damn! Listen to that wind!

[FROM an interview with Dr. Pamela Prentiss.]

I didn’t see Jennie at all from the time the project ended in the summer of 1973 until spring of 1974. Almost a year. Without a structured environment, Jennie became very difficult. She was also starting to reach sexual maturity. Naturally, the Archibalds wanted to get rid of her. So they asked me if I would take her to the Tahachee Island Rehabilitation Center. This was a center I had started for rehabilitating laboratory chimpanzees. It was also a breeding colony of chimpanzees in the United States. There is, you see, the very real possibility of the chimpanzee becoming extinct in the wild. If things keep going on the way they are in Africa, it will be inevitable.

Now, I knew this was coming. I expected it. No family has ever kept a home-raised chimp past sexual maturity. When that happened, I was going to bring Jennie to the Barnum colony, you see, where she would have a huge area to play and be herself while she got used to the other chimps.

The Tahachee Center was a second-best option. It wasn’t nearly as elaborate as the Barnum colony, but it was pretty good. I thought it would be a nice place for Jennie. Much better than the chaos of the Archibald household. The Tahachee Center was being generously funded by the MacBruce Foundation. Thank God we weren’t dependent on government funding. We had the direct support of Simon MacBruce. MacBruce is a fiercely independent type, and he didn’t give two hoots for the Proxmire flap. It made Miller so mad to see me get the MacBruce grant!

The center is still going, by the way, and we now have forty-two very happy chimpanzees there. While they must be supplementally fed, they’ve adjusted to the semiwild life of the island very well. It’s been an unqualified success.

[FROM an interview with Lea Archibald.]

After Dr. Prentiss and Harold left, I remember that Hugo and I talked. The island reminded us of how much Jennie loved Hermit Island, and we talked about what a perfect environment it had been. We also talked about what it means to grow up. At a certain point, parents have to let go of their children. We felt that Jennie’s problems stemmed from her efforts to become independent. But you see, the problem was that Jennie wasn’t a human being so she couldn’t just “become independent.” She wasn’t like Sandy, who could move out, get a job, and find an apartment. Her rebellion could go nowhere.

We talked, and we cried, and we talked some more. Oh dear. Hugo was terribly upset at the whole thought of giving Jennie up. I was too, but not like Hugo. To let her go was the hardest decision we ever made. We talked to Sandy and Sarah about it. Sandy was violently opposed to the idea. He was so angry at us. It was awful. He threw a chair through the picture window in the living room. Oh dear, that was a terrible moment. Sarah said that whatever we decided would be all right with her.

We didn’t accept Dr. Prentiss’s proposal right away. Hugo first looked into other possible research projects or primate centers. He researched everything. There were several around the country, but all of them kept the chimpanzees in cages. There was a primate rehabilitation project starting in Africa, but that was mostly for chimpanzees confiscated from poachers, and it was a much rougher setting. The chimpanzees there were wild animals, really, and we didn’t feel Jennie would do well there. After all, Jennie had never seen another chimpanzee in her entire life. Not one.

Finally, Hugo and I decided to accept Dr. Prentiss’s proposal. I remember when Hugo made the phone call. He dialed her number and then he couldn’t even speak into the phone he was so choked up. I could hear her nasty little voice coming through the receiver, demanding to know who it was, and then Hugo just hung up. It’s so painful now to remember. How I wish he’d just left it at that. But he called her right back and said that, yes, we would accept her offer. Naturally, we wanted to see the setup and the island, and meet the caregivers. They didn’t call them “keepers” since they wanted to avoid the image of a zoo, you see.

So we flew down there... Excuse me... I’m a little upset. Look at me, already starting to cry. We flew down there and looked the place over... Please forgive me. I’m just a useless old lady. It was seventeen years ago but it still seems like yesterday. It’s hard for me to talk about this...

[Editor’s note: At this point Mrs. Archibald excused herself and the interview was resumed the following day.]

The place was so pretty. The island was about a mile wide and two miles long, quite sandy, with lots of eucalyptus trees, pines, and palmettos. The beaches were sandy and the water was so blue.

Sandy wouldn’t come. He disappeared for several days. To his girlfriend’s house. She had a dreadful alcoholic mother and she and her sister pretty much ran around like wild animals.

Читать дальше