Republic of Armenia

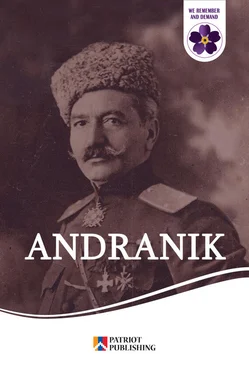

Andranik

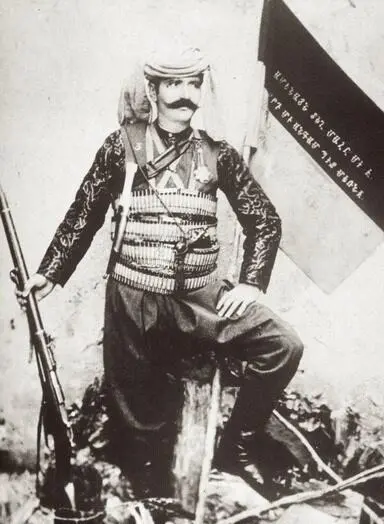

General Andranik c.1920

Andranik Ozanian, commonly known as Andranik (Armenian: Անդրանիկ; 25 February 1865 – 31 August 1927) was an Armenian military commander and statesman, the best known fedayi and a key figure of the Armenian national liberation movement. He became active in an armed struggle against the Ottoman government and Kurdish irregulars in the late 1880s. He joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktustyun) party and, along with other fedayi (militias), sought to defend the Armenian peasantry living in their ancestral homeland, an area known as Turkish (or Western) Armenia – at the time part of the Ottoman Empire. His revolutionary activities ceased and he left the Ottoman Empire after the unsuccessful uprising in Sasun in 1904. In 1907, Andranik left Dashnaktustyun because he disapproved of its cooperation with the Young Turks, a party which years later perpetrated the Armenian Genocide. Between 1912 and 1913, together with Garegin Nzhdeh, Andranik led a few hundred Armenian volunteers within the Bulgarian army against the Ottomans during the First Balkan War.

From the early stages of World War I, Andranik commanded the first Armenian volunteer battalion and led them within the Russian Imperial army against the Ottoman Empire. After the Revolution of 1917, the Russian army retreated and left the Armenian irregulars outnumbered against the Turks. Andranik led the defense of Erzurum in early 1918, but was forced to retreat eastward. By May 1918, Turkish forces stood near Yerevan – the future Armenian capital. The Dashnak-dominated Armenian National Council declared the independence of Armenia and signed the Treaty of Batum with the Ottoman Empire, by which Armenia gave up its rights to Western Armenia. Andranik never accepted the existence of the First Republic of Armenia because it included only a small part of the area many Armenians hoped to make independent. Andranik, independently from the Republic of Armenia, fought in Zangezur against the Azerbaijani and Turkish armies and helped to keep it within Armenia.

Andranik left Armenia in 1919 due to disagreements with the Armenian government and spent his last years of life in Europe and the United States seeking relief for Armenian refugees. He settled in Fresno, California in 1922 and died five years later in 1927. Andranik is greatly admired as a national hero by Armenians; numerous statues of him have been erected in several countries. Streets and squares were named after Andranik, and songs, poems and novels have been written about him, making him a legendary figure in Armenian culture.

Andranik Ozanian was born on 25 February 1865, in Shabin-Karahisar, Sivas Vilayet, Ottoman Empire – today in Turkey's Giresun Province – to Mariam and Toros Ozanian. Andranik means "firstborn" in Armenian. His paternal ancestors came from the nearby Ozan village in the early 18th century and settled in Shabin-Karahisar to avoid persecution from the Turks. His ancestors took the surname Ozanian in honor of their hometown. Andranik's mother died when he was one year old and his elder sister Nazeli took care of him. Andranik went to the local Musheghian School from 1875 to 1882 and thereafter worked in his father's carpentry shop. He married at the age of 17, but his wife died a year later while giving birth to their son – who also died days after the birth.

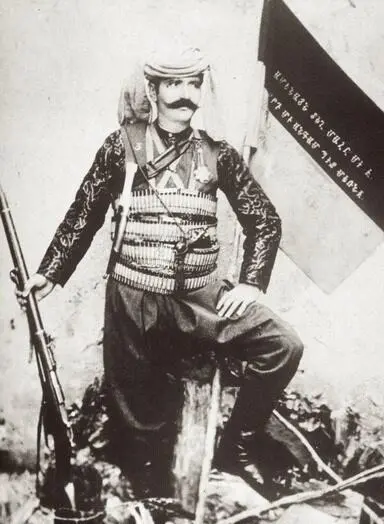

An undated photo of Andranik holding a rifle

The situation of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had worsened under the reign of Abdul Hamid II, who sought to unify all Muslims under his rule. In 1882, Andranik was arrested for assaulting a Turkish gendarme for mistreating Armenians. With the help of his friends, he escaped from prison. He settled in the Ottoman capital Constantinople in 1884 and stayed there until 1886, working as a carpenter. He began his revolutionary activities in 1888 in the province of Sivas. Andranik joined the Hunchak party in 1891. He was arrested in 1892 for taking part in the assassination of Constantinople's police chief, Yusup Mehmet Bey – known for his anti-Armenianism – on 9 February.Andranik once again escaped from prison. In 1892, he joined the newly created Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun). During the Hamidian massacres, Andranik with other fedayi defended the Armenian villages of Mush and Sasun from attacks of the Turks and the Kurdish Hamidiye units. The massacres, which occurred between 1894 and 1896 and are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, killed between 80,000 and 300,000 people.

In 1897, Andranik went to Tiflis – the largest city of the Caucasus and a major center of Armenian culture at the time – where the ARF headquarters was located. Andranik returned to Turkish Armenia "entrusted with extensive powers, and with a large supply of arms" for the fedayi.Several dozen Russian Armenians joined him, with whom he went to the Mush-Sasun area where Aghbiur Serob was operating.Serob's forces had already established semi-independent Armenian areas by expelling the Ottoman government representatives.

An undated photo of Andranik holding a rifle

The Holy Apostles Monastery of Mush

Aghbiur Serob, the main leader of the fedayi in the 1890s, was killed in 1899 by a Kurdish chieftain, Bushare Khalil Bey.Months later, Bey committed further atrocities against the Armenians by killing a priest, two young men and 25 women and children in Sasun's village of Talvorik. Andranik replaced Serob as the head of the Armenian irregular forces "with 38 villages under his command" in the Mush-Sasun region of Western Armenia, where a "warlike semi-independent Armenian peasantry" lived. Andranik sought to kill Bey; he captured and reportedly decapitated the chieftain, and took the medal given to Bey by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Andranik thus earned an undisputed authority among his fedayi.

Although small groups of Armenian fedayi conducted an armed struggle against the Ottoman state and the Kurdish tribes, the situation in Turkish Armenia deteriorated as the European powers stood indifferent to the Armenian Question. Article 61 of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin intended the Ottoman government to "carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by the Armenians, and to guarantee their security against the Circassians and Kurds" remained unimplemented.According to Christopher J. Walker, the attention of the European powers was on Macedonia, while Russia was "in no mood for reactivating the Armenian question".

Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery

In November 1901 the fedayi clashed with the Ottoman troops in what later became known as the Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery. One of the best-known episodes of Andranik's revolutionary activities, it was an attempt by the Ottoman government to suppress his activities. Since Andranik had gained more influence over the region, more than 5,000 Turkish soldiers were sent after him and his band. The Turks chased and eventually circled him and his men, numbering around 50, at the Arakelots (Holy Apostles) Monastery in early November. A regiment under the command of Ferikh Pasha and Ali Pasha besieged the fort-like monastery. The Turkish generals leading the army of twelve hundred men asked the fedayi to negotiate their surrender.

After weeks of resistance and negotiations – in which Armenian clergy and the headman of Mush and foreign consuls took part – Andranik and his companions left the monastery and fled in small groups. According to Leon Trotsky, Andranik – dressed in the uniform of a Turkish officer – "went the rounds of the entire guard, talking to them in excellent Turkish", and "at the same time showing the way out to his own men." After breaking through the siege of the monastery, Andranik gained legendary stature among provincial Armenians. He became so popular that the men he led came to refer to him always by his first name. Andranik intended to attract the attention of the foreign consuls at Mush to the plight of the Armenian peasants and to provide hope for the oppressed Armenians of the eastern provinces. According to Trotsky, Andranik's "political think took shape in a setting of Carbonarist activity and diplomatic intrigue."

Читать дальше