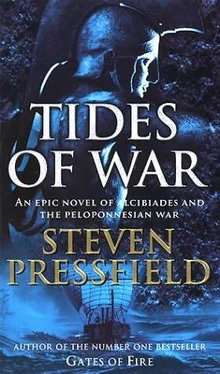

Steven Pressfield - Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Pressfield - Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторические приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At that time Socrates' summers had passed seventy, yet he appeared save his beard gone white and the noble amplitude of his girth much as Polemides described during the siege of Potidaea.

His limbs stood hale and sturdy, his carriage vigorous and purposeful; it required scant imagination to picture the veteran snatching up shield and armor to advance once again into the fray.

Not surprisingly the philosopher evinced curiosity about his fellow inmate and even advanced counsel upon how best to defend him. “It is too late to file a countersuit, a paragraphe, declaring his indictment unlawful, which of course it is. Perhaps a dike pseudomartyriou, a suit for false witness, which may be invoked up to the moment of the jury's vote.” He laughed. “You see, my own ordeal has rendered me something of a jailhouse lawyer.”

We discussed the Amnesty, in place since the restoration of the democracy, which exempted all citizens from prosecution for crimes committed theretofore. “Polemides' enemies have gotten around this cleverly, Socrates, by charging him with 'wrongdoing.'

That rakes a lot of mud, and, as he admits, there is more than enough with which to tar him.” I narrated an abridged version of Polemides' story, what he had told me thus far.

“I knew several of his family,” Socrates remarked when this chronicle concluded. “His father, Nicolaus, was a man of exceptional integrity, who perished in attendance upon the stricken during the Plague. And I enjoyed a cordial if chaste acquaintance with his great-aunt Daphne, who effectively ran the Board of Naval Governors through her second and third husbands. She was the first of the aristocratic dames, in her widowhood, to conduct her affairs entirely on her own, with no male as kyrios or guardian, and not even a servant about the house.”

Our master expressed concern for Polemides' comfort. “The heat is stifling on that side of the court, I hear. Please, Jason, take him this fruit, and that wine; I may imbibe no more, as they say it spoils the savor of hemlock.”

When the others returned with the evening, some measure of amusement was wrung from the coincident confinement of the murderer and the philosopher. Crito, Socrates' wealthiest and most devoted follower, spoke. In the days prior to our master's trial, he had hired detectives and set about acquiring intelligence of the philosopher's accusers, seeking to bring to light their private crimes and thus discredit them and their indictments. It occurred to me now that I might do the same for Polemides.

I had then in my employ a married couple of middle years, Myron and Lado. They were incorrigible snoops, both, who delighted in nothing more than digging up dirt on the high and mighty. I decided to set these bloodhounds to work. What had become of Polemides' family? What motivated his accusers? Had someone put them up to this, and if so, who? What covert agenda did they seek to promote?

Meanwhile, my grandson, I sense your assimilation of this tale wanting. You need more background. Polemides and I were contemporaries; he knew as he spoke that I understood the times and required no exposition as to their feel and flavor. You of a later generation, however, may benefit by a brief historical digression.

In the years before the War, that period of my own and our narrator's boyhood, Athens stood not in the state of faded glory within which she currently resides. Her best days were not behind her, but present, to hand, dazzling and incandescent. Her navy had routed the Empire of Asia and driven the Persian from the sea.

Tribute flowed to her from two hundred states. She was a conqueror, an empire, the cultural and commercial capital of the world.

The Spartan War lay years in the future, yet already Pericles' vision had inspired him to prepare for it. He fortified the harbors at Munychia and Zea, reinforced the Long Walls along their entire length, and built the Southern Wall, the “Third Leg,” that, should the Northern or Phalerian Wall fall, the city would remain impregnable.

You, my grandson, who have known these adamant marvels or their restored rendition all your life, take their existence for granted. But at that time they were a feat of engineering such as no city of Greece had ever dreamt, let alone dared. To extend the city's battlements, four and a half miles on one side, nearly the same on the other, yoking the upper city to the harbors at Piraeus, bounding these as well on all sides save the sea, thus turning Athens into an island of invincible fortification…this was considered folly by most and madness by many.

My own father and the main of the equestrian class had stood in violent opposition to this enterprise, opposing first Themistocles, then Pericles implementing the former's policy. They discerned clearly, the landholders of Attica, that the Olympian, as Pericles was called, intended when war came to leave defenseless before the invader, and in fact abandon, our estates, farms, and vineyards, including this one above whose fields you and I now sit. Pericles' strategy would be to withdraw the citizenry behind the Long Walls, permitting the foe to ravage our farmsteads at will. Let them deplete their warrior spirit in the slave's tasks of chopping vines and torching garners. When they got bored enough, they would go home. Meanwhile Athens, which controlled the sea and could procure its needs from the states of its empire, would peer down contemptuously upon the invader, secure behind her impregnable battlements.

All revolved about the navy.

The great houses of Athens, the nobles of the Cecropidae, Alcmaeonidae, and Peisistratidae, the Lycomidae, Eumolpidae, and Philaidae, all prided themselves as knights and hoplites. Their ancestors and they themselves had defended the nation as cavalrymen or gentleman warriors of the armored infantry. Now Athens had devolved into a nation of oar pullers. The fleet employed and emboldened the commons, and the commons packed the Assembly. They hated it, the aristocracy, but were powerless to resist the tide of change. Besides, the navy was making them rich. Reforms initiated by Pericles and others established pay for public service, appointing officials by lot rather than ballot, thus stacking the magistracies and the courts with hoi polloi, the many. To those of the “Party of the Good and True” who expressed revulsion at the spectacle of our city's champions slouching down harbor lanes bearing their oars and cushions, Pericles responded that it was not his policies that had made Athens a naval power and an empire. History had done it. It was our fleet, manned by our citizen crews, which had defeated Xerxes at Salamis; our fleet which had chased the Persian from the seas; our fleet which had restored freedom to the islands and the Greek cities of Asia. And our fleet that was hauling in, and enriching us all with, the wealth of the world.

The construction of the Long Walls was no gauntlet flung into the teeth of history, Pericles argued, but recognition plain and simple of the reality of the time. We would never beat the Spartans on land. Their army was invincible and always would be. Athens' destiny lay at sea, as Apollo himself had decreed, declaring, the wooden wall alone shall not fail you, and as Themistocles and Aristides had proved at Salamis, and Cimon and all our conquering generals in the succeeding generation, including Pericles himself, had confirmed again and again.

Others inveighed against this policy of “walls and ships,” declaring that imperial expansionism would inflame, and had inflamed, mistrust of us among the Spartans. Leave them in peace and they will leave us. But push them into a corner, show up their pride by our ever-enlarging power, and they will be compelled to respond in kind.

This was true and Pericles never refuted it. Yet such was the brass, the crust, the arrogance of those years that Athens' citizenry disdained accommodation of other states as her tradesmen and even her whores scorned to vacate for their betters the public way.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tides of War, a Novel of Alcibiades and the Peloponnesian War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.