Ernest Seton - Two Little Savages

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ernest Seton - Two Little Savages» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Жанр: Детские приключения, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Two Little Savages

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Two Little Savages: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Two Little Savages»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Two Little Savages — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Two Little Savages», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Biddy's remark about the Indian tobacco bore fruit. Yan was not a smoker, but now he felt he must learn. He gathered a lot of this tobacco, put it to dry, and set about making a pipe—a real Indian peace pipe. He had no red sandstone to make it of, but a soft red brick did very well. He first roughed out the general shape with his knife, and was trying to bore the bowl out with the same tool, when he remembered that in one of the school-readers was an account of the Indian method of drilling into stone with a bow-drill and wet sand. One of his schoolmates, the son of a woodworker, had seen his father use a bow-drill. This knowledge gave him new importance in Yan's eyes. Under his guidance a bow-drill was made, and used much and on many things till it was understood, and now it did real Indian service by drilling the bowl and stem holes of the pipe.

He made a stem of an Elderberry shoot, punching out the pith at home with a long knitting-needle. Some white pigeon wing feathers trimmed small, and each tipped with a bit of pitch, were strung on a stout thread and fastened to the stem for a finishing touch; and he would sit by his camp fire solemnly smoking—a few draws only, for he did not like it—then say, "Ugh, heap hungry," knock the ashes out, and proceed with whatever work he had on hand.

Thus he spent the bright Saturdays, hiding his accouterments each day in his shanty, washing the paint from his face in the brook, and replacing the hated paper collar that the pride and poverty of his family made a daily necessity, before returning home. He was a little dreamer, but oh! what happy dreams. Whatever childish sorrow he found at home he knew he could always come out here and forget and be happy as a king—be a real King in a Kingdom wholly after his heart, and all his very own.

XII

A Crisis

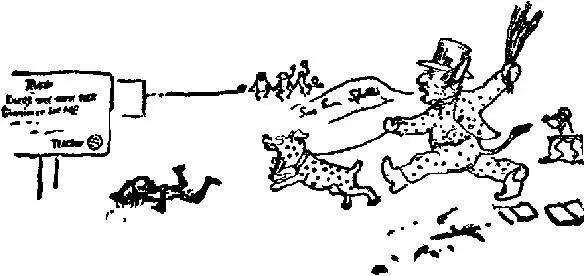

At school he was a model boy except in one respect—he had strange, uncertain outbreaks of disrespect for his teachers. One day he amused himself by covering the blackboard with ridiculous caricatures of the principal, whose favourite he undoubtedly was. They were rather clever and proportionately galling. The principal set about an elaborate plan to discover who had done them. He assembled the whole school and began cross-examining one wretched dunce, thinking him the culprit. The lad denied it in a confused and guilty way; the principal was convinced of his guilt, and reached for his rawhide, while the condemned set up a howl. To the surprise of the assembly, Yan now spoke up, and in a tone of weary impatience said:

"Oh, let him alone. I did it."

His manner and the circumstances were such that every one laughed. The principal was nettled to fury. He forgot his manhood; he seized Yan by the collar. He was considered a timid boy; his face was white; his lips set. The principal beat him with the rawhide till the school cried "Shame," but he got no cry from Yan.

That night, on undressing for bed, his brother Rad saw the long black wales from head to foot, and an explanation was necessary. He was incapable of lying; his parents learned of his wickedness, and new and harsh punishments were added. Next day was Saturday. He cut his usual double or Saturday's share of wood for the house, and, bruised and smarting, set out for the one happy spot he knew. The shadow lifted from his spirit as he drew near. He was already forming a plan for adding a fireplace and chimney to his house. He followed the secret path he had made with aim to magnify its secrets. He crossed the open glade, was, nearly at the shanty, when he heard voices—loud, coarse voices— coming from his shanty . He crawled up close. The door was open. There in his dear cabin were three tramps playing cards and drinking out of a bottle. On the ground beside them were his shell necklaces broken up to furnish poker chips. In a smouldering fire outside were the remains of his bow and arrows.

Poor Yan! His determination to be like an Indian under torture had sustained him in the teacher's cruel beating and in his home punishments, but this was too much. He fled to a far and quiet corner and there flung himself down and sobbed in grief and rage—he would have killed them if he could. After an hour or two he came trembling back to see the tramps finish their game and their liquor; then they defiled the shanty and left it in ruins.

The brightest thing in his life was gone—a King discrowned, dethroned. Feeling now every wale on his back and legs, he sullenly went home.

This was late in the summer. Autumn followed last, with shortening days and chilly winds. Yan had no chance to see his glen, even had he greatly wished it. He became more studious; books were his pleasure now. He worked harder than ever, winning honour at school, but attracting no notice at the home, where piety reigned.

The teachers and some of the boys remarked that Yan was getting very thin and pale. Never very robust, he now looked like an invalid; but at home no note was taken of the change. His mother's thoughts were all concentrated on his scapegrace younger brother. For two years she had rarely spoken to Yan peaceably. There was a hungry place in his heart as he left the house unnoticed each morning and saw his graceless brother kissed and darlinged. At school their positions were reversed. Yan was the principal's pride. He had drawn no more caricatures, and the teacher flattered himself that that beating was what had saved the pale-faced head boy.

He grew thinner and heart-hungrier till near Christmas, when the breakdown came.

"He is far gone in consumption," said the physician. "He cannot live over a month or two"

"He must live," sobbed the conscience-stricken mother. "He must live—O God, he must live."

All that suddenly awakened mother's love could do was done. The skilful physician did his best, but it was the mother that saved him. She watched over him night and day; she studied his wishes and comfort in every way. She prayed by his bedside, and often asked God to forgive her for her long neglect. It was Yan's first taste of mother-love. Why she had ignored him so long was unknown. She was simply erratic, but now she awoke to his brilliant gifts, his steady, earnest life, already purposeful.

XIII

The Lynx

As winter waned, Yan's strength returned. He was wise enough to use his new ascendency to get books. The public librarian, a man of broad culture who had fought his own fight, became interested in him, and helped him to many works that otherwise he would have missed.

"Wilson's Ornithology" and "Schoolcraft's Indians" were the most important. And they were sparkling streams in the thirst-parched land.

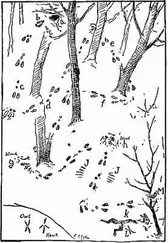

In March he was fast recovering. He could now take long walks; and one bright day of snow he set off with his brother's Dog. His steps bent hillward. The air was bright and bracing, he stepped with unexpected vigour, and he made for far Glenyan, without at first meaning to go there. But, drawn by the ancient attraction, he kept on. The secret path looked not so secret, now the leaves were off; but the Glen looked dearly familiar as he reached the wider stretch.

His eye fell on a large, peculiar track quite fresh in the snow. It was five inches across, big enough for a Bear track, but there were no signs of claws or toe pads. The steps were short and the tracks had not sunken as they would for an animal as heavy as a Bear.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Two Little Savages»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Two Little Savages» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Two Little Savages» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.