Bastian Zach, Matthias Bauer

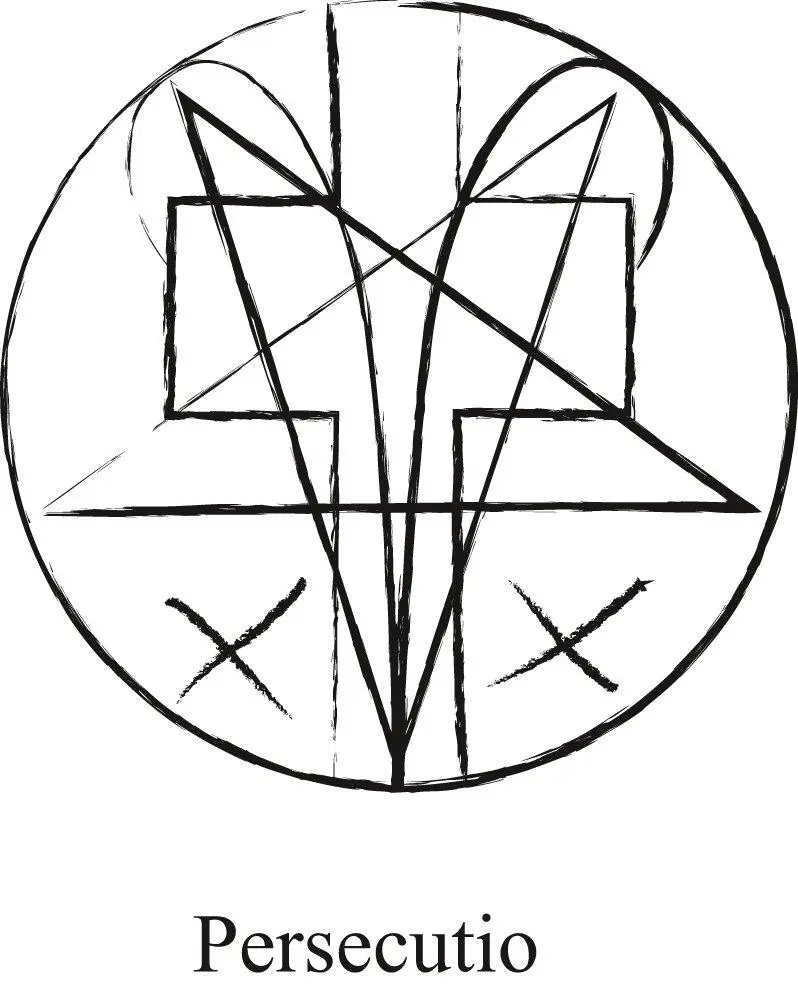

Morbus Dei: The Sign of Aries

Bastian Zach

Matthias Bauer

Morbus Dei: The Sign of Aries

Novel

Translated from the German language by Claire Speringer

Originally published in German language as Morbus Dei: Im Zeichen des Aries

© 2013 by Haymon Verlag

Erlerstraße 10, A-6020 Innsbruck

E-Mail: office@haymonverlag.at

www.haymonverlag.at

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced and electronically processed, duplicated or distributed without the written approval of Haymon Verlag.

ISBN 978-3-7099-3633-7

English translation: Claire Speringer

Cover picture: www.istockphoto.com, Bastian Zach

Author photo: Sabine Zach

Depending on the reading device used, varying depictions of the published texts are possible.

… one part angelica, two parts rue, one part dried toad powder, four parts honey and two parts aniseed.

Grind the ingredients and mix them carefully to form a glutinous paste. Let the paste stand for three days and three nights until it is dry.

The old abbot laid the quill to one side and blew on the ink to dry it. He gazed with satisfaction at the transcript he had made of the pages when suddenly there was a creak.

He froze. Nothing. It must have been the woodwork breathing, he thought with a chuckle.

A couple of logs were gently smouldering in the fireplace and the one solitary candle in the otherwise dark library began to splutter. In the flickering light, the abbot scrutinized what he had written and carefully compared it a final time with the original, for he knew that the omission of one single ingredient could have dire consequences.

However everything was as it should be. He let out a deep sigh and all at once the feeling of tension that had dogged him for the past few days melted away.

He stroked his stubbly, snow-white beard. Wasn’t it only yesterday that it had been dark brown? Or was that decades ago? He looked down at his bony hands, all sprinkled with liver spots.

Tempus fugit.

The abbot folded the transcript and placed it in a little leather bag hanging from his belt.

There was a bang and the heavy wooden door flew open and three men wearing the robes of the Dominican Order burst into the library. They glared at the abbot.

‘You’ve had long enough to look for them,’ piped up one of the men.

‘Yes, and now I’ve found them,’ replied the abbot, his heart pounding with trepidation as he reached towards the loose papers on the table. He gathered them up and handed them to the men.

One of them snatched the papers and flicked through them.

‘Well? Are they them?’ asked one of the friars behind him.

The Dominican nodded. Then he went briskly towards the fireplace and threw them into the fire. The flames licked at the pages, their edges curling in the heat, and in a short while they were nothing but ash.

A draught caught the tiny white fragments, making them dance and swirl in the air until they finally vanished up the chimney.

Gone forever, thought the old abbot, that’s what would have happened.

Without another word, the Dominicans departed. The abbot watched them disappear down the dark corridor. Thoughtfully, he stroked his leather bag.

No doubt they thought they had acted for the good of mankind in general, and for the good of the church in particular.

Which is what I too have done.

There was the sound of hurried footsteps and he looked up. A novice came running along the corridor and stopped in the doorway, tears in his eyes.

‘Brother Martin’s life is coming to an end,’ he panted. ‘Please come, he’s asking for you, Abbot Bernardin!’

Vienna,

Anno Domini 1704

The thunderstorm, which had rained down on Vienna as if it were bent on drowning the old imperial city, had blown over before sunrise, leaving a cloudless sky. There was a mild, early summer breeze blowing and the sun shone down, drying up the mud and the puddles.

Lunch over, the farmers were back at work and hardly noticed the thin plume of smoke spiralling into the sky above the hilltops in the north.

Yesterday there had been a real spectacle. The entire imperial city had gone up in flames, at least that was what some people had believed. The prospect had made them rub their hands together with no small amount of glee: at last the stinking rich city folk would find out what it was like to lose everything, something they had had the misfortune to experience at the hands of the Turks during the last siege.

However, towards evening, the glow of the distant fire began to die down and it was clear that the city and its inhabitants had survived.

So the farmers went back to the grindstone and paid no attention to the convoy of waggons bumping along the highway, escorted by a dozen men on horseback. Variously armed, with grim expressions and no uniforms, it was obvious to all that they were mercenaries.

At the head of the convoy was a black carriage, its curtains tightly pulled, and behind it two heavy box waggons with wide, ironclad wheels and covered with leather tarpaulin. A provisions waggon was bringing up the rear. Escorts were riding in front and behind the expedition, their eyes peeled for obstacles or troublemakers.

François Antoine Gamelin, Special Envoy and Maréchal de camp of the French army, had always disliked the rhythmic swaying of a carriage, for, in his opinion, it lulled the occupants into an illusory world of unreality. He hated to travel like an effete nobleman and would much rather have had a hard saddle under him and the wind in his face, something which his current position did not allow. He peered through the gap between the curtains at the luscious green meadows and was annoyed with himself for feeling annoyed. He had no reason to be out of sorts for he had brought off a coup that very morning that would win him the admiration of all the generals: he was carrying in the two waggons behind him precious military fodder that would prove decisive for the war. Fodder that he had secretly smuggled out of Vienna.

Twirling his moustache complacently, he turned away from the window. In front of him was a piece of that fodder in the shape of a young woman. She was pressed up against the sumptuous upholstery, with her eyes lowered. Her dress was worn to threads, and her dark hair hung down in strands over her pale, freckled face. On her left cheek was a flame-red mark, just beginning to turn bluish.

Gamelin had managed to capture her at the very last moment. She was the key to everything that had happened in Vienna, the spark that had kindled a veritable conflagration. Gamelin saw himself as the custodian of that spark. He had even managed to prise out of her the location of the village where it had all started. This information was his safeguard, should anything happen to his precious cargo and he be in need of replacements.

Now that she had told him what he had wanted to know he had no further use for her.

He waved his hand casually out of the window and the carriage came to a standstill. Two mercenaries came running up and opened the door. ‘I bid you farewell and thank you, ma chère Elisabeth,’ said Gamelin, nodding to the soldiers. They grabbed the young woman and dragged her out of the carriage.

She offered no resistance and, submitting to the men’s rough treatment of her, stumbled along the muddy road to the rear of the next waggon behind the carriage. She still couldn’t think straight, couldn’t make head or tail of what had happened, to her and to all of them.

Читать дальше