Dictionaries of text-messaging list hundreds of acronyms and give the impression that a new language, textese , has emerged. In fact, now that collections of real text messages have been made and studied, it transpires that only a few of those abbreviations are used with any frequency. Replacing see by c , you by u and to by 2 are some of the commonly used strategies. But the kind of message in which every word is an abbreviation ( thx 4 ur msg c u 18r ) is really rather unusual. On average, only about 10 per cent of the words in a text are abbreviated. And in many adult texting situations, textisms are frowned upon, or even banned, because the organisers know that not everyone will understand them.

The novelty of texting abbreviations has also been overestimated. Several were actually part of computer interaction in chatrooms long before texting arrived in the late 1990s. And some can be traced back over many years. In a poem called ‘An Essay to Miss Catherine Jay’, an anonymous author begins:

An S A now I mean 2 write

2 U sweet K T J…

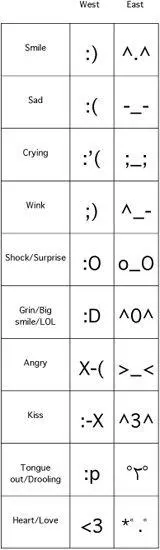

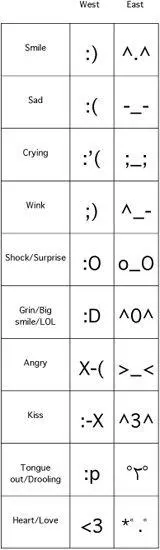

20. An illustration of cultural differences in the use of emoticons. In Western countries, emoticons are viewed sideways and focus on the mouth; in the East, they are horizontal and focus on the eyes.

It was published in 1875. Lewis Carroll and Queen Victoria are among the many Victorians who played with such sound/letter substitutions.

On the other hand, there’s nothing in older usage that quite lives up to the modern penchant for taking an abbreviation and adding to it. Thus, from the basic form imo (‘in my opinion’) we find imho (‘in my humble opinion’), imhbco (‘in my humble but correct opinion’) and imnsho (‘in my not so humble opinion’). And a similar thing happens to the other big innovation of contemporary electronic communication: the emoticon or smiley. Based on :), used to express a friendly reaction, we find :)), :))) and other extensions conveying increased intensity of warmth.

It’s difficult to say how many of the novel computer abbreviations will remain in the language, once the novelty has worn off. Txt , txtng and related forms may survive, but only as long as the technology does. And who can say whether, in fifty years’ time, people will still be typing such forms as brb (‘be right back’) and afaik (‘as far as I know’) and sending each other combinations of cat pictures + non-standard grammar ( lolcats )? Will there still be keyboards and keypads then, even, or will everything be done through automatic speech recognition? With electronic communication, as I said earlier ( §32), we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century)

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century)

Since 1990, members of the American Dialect Society have voted on the ‘Word of the Year’ ( §91). The selection reflects social as much as linguistic factors. In 1999, they chose Y2K . In 2001, 9–11 . And the economic crisis of recent years is reflected in sub-prime for their 2007 choice and bailout for 2008. It’s thus something of a relief to find tweet their selection for 2009 ( §100).

Choosing a word for a year is difficult enough. Much more difficult is a ‘Word of the Decade’. In 2010 the members of the Society chose google . That seems fair enough. But what would you do for the ‘Word of the Century’?

They chose jazz . It was perhaps bending the truth a little, but not much. The word doesn’t surface until the century is over ten years old. In 1913, a San Francisco commentator described jazz as ‘a futurist word which has just joined the language’. However, he wasn’t referring to the musical sense, which didn’t arrive until a couple of years later. He meant jazz as a slang term for ‘pep’ or ‘excitement’. It also meant ‘excessive talk, nonsense’. This general sense is still known in the expression and all that jazz , meaning ‘and stuff like that’. As an adjective, it developed a wide range of senses — ‘lively’, ‘vivid’, ‘sophisticated’. There were jazz dances and jazz patterns (in clothing and furniture); there was jazz journalism and jazz language . Today we’d say jazzy .

The music sense is first recorded in the Chicago press of 1915 — and it quickly took off. It was used to describe hundreds of notions associated with the music — types of music ( jazz blues, jazz classics ), musical instruments ( jazz guitar, jazz clarinet ), players and singers ( jazz pianist, jazz vocalist ) and performing groups ( jazz quartet, jazz combo ). Virtually all the terms we now associate with jazz ( band, club, music, singer, records ) were in use by the end of the 1920s.

The word acquired more applications as the century progressed. New musical trends motivate fusions, so we find such phrases as jazz-rock , jazz-funk and jazz-rap . In the 1950s and ’60s, we encounter jazzetry (‘reading poetry to jazz’) and jazzercise (‘performing physical exercises to jazz’). In the 1990s, we find jazz cigarettes (‘marijuana’).

The early practitioners of jazz knew that they were living through a musical revolution: jazz era is first used in 1919; jazz age in 1920. Not everyone would agree with the voting of the Society members, which probably reflects their musical interests as much as anything else, but to my mind it was quite a good choice.

96. Sudoku — a modern loan (21st century)

96. Sudoku — a modern loan (21st century)

Sudoku has been in Japanese at least since the 1980s, when the game was first devised, but it didn’t appear as a loanword in English until 2000, one of the first borrowings of the new millennium. It continued a trend to take words from Japanese that had been building up in the second half of the 20th century.

Karaoke seems to have been with us for ever, but its first recorded use in English is only 1979. And since 1950 increased tourism and international business has brought hundreds of words into English from Japanese, many quite specialised. If you’re into sumo wrestling, for example, your loanwords will be quite extensive, such as yokozuna (‘highest rank of wrestler’), dohyo (‘the sumo ring’), okuridashi (‘a pushing technique’) and torikumi (‘a bout’). The business world will make you familiar with shoshas (‘trading houses’), kanban (‘a just-in-time production method’), kaizen (‘improvements in practice’) and zaitech (‘financial engineering’).

Gardeners will know bonsai (‘dwarf plants’). Film buffs will know anime (‘animated films’). Artists will know shunga (‘erotic art’). Those who practise alternative medicine will know shiatsu (‘a finger-pressure therapy’). Martial arts practitioners will know shuriken (‘a type of weapon’) and, of course, karate . Cooks will know dashi (‘cooking stock’), tamari (‘soy sauce’) and teriyaki (‘a type of fish or meat dish’). Tourists will have travelled on the Shinkansen train and perhaps stayed in a ryokan (‘a traditional inn’). Hopefully they will not have encountered a yakuza (‘gangster’). At home they may still have a rusting Betamax — a name often thought to be a Greek coinage, but in fact from Japanese beta ‘all over’ + max ( imum ).

Читать дальше

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century)

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century) 96. Sudoku — a modern loan (21st century)

96. Sudoku — a modern loan (21st century)