Bush itself was one of these changes of sense, referring to the huge expanse of natural countryside that formed inland Australia. It became the basis of a wide range of expressions, such as bush mouse and bush turkey , bush cucumber and bush tomato , bush ballad and bush medicine . Few have travelled outside Australia. An exception is bush telegraph , meaning the rapid spread of news or rumours.

Words from British regional dialects often underlie an Australian usage. Dinkum is a case in point. This is one of the best-known Australianisms, especially in the phrase fair dinkum . It appears in the 19th century in Britain, and is recorded by Joseph Wright in his English Dialect Dictionary . He found dinkum in Derbyshire and fair dinkum in Lincolnshire. Dinkum meant ‘hard work’, and fair dinkum was your ‘fair share of work’.

These senses travelled to Australia, but soon developed more general meanings of ‘honest, genuine’ and ‘good, excellent’, which is how the word is used today. Its popularity is suggested by the way it developed alternative forms, shortening to dink and lengthening to dinki-di . The origin of the word isn’t known. There are other uses, such as dink meaning ‘finely dressed’ and dinky meaning ‘neat, small’, all with a history in British dialects, but it’s difficult to see how they relate to the Australian use.

Thanks to the international popularity of Australian films and TV programmes, the English-speaking world has come to be familiar with dinkum and other informal expressions such as cobber (‘mate’), pom (‘British person’), sheila (‘woman’), tucker (‘food’) and g’day (as a greeting), as well as abbreviated forms such as beaut (as a term of praise) and arvo (‘afternoon’). Just occasionally, a colloquialism becomes part of international informal English. Barbies (‘barbecues’) have been with us since the 1970s.

The down side of media presence is that it often paints an exaggerated picture of Australian English. Outsiders hear colourful phrases and assume that everyone talks in the same way. Books of Australianisms have collected such expressions as miserable as a bandicoot , flat out like a lizard drinking and he couldn’t find a grand piano in a one-roomed house , but it’s debatable just how many people have actually ever used them.

69. Mipela — pidgin English (19th century)

69. Mipela — pidgin English (19th century)

You won’t find mipela or mifela in a dictionary of standard English, but these words belong to the language nonetheless — used in different varieties of pidgin English. Mipela is one of the pronouns used in the pidgin language of Papua New Guinea called Tok Pisin (‘Pidgin Talk’). People generally have a low opinion of pidgin languages. They think of them as primitive compared with standard English, with little or no grammar and a tiny vocabulary.

In fact, a pidgin like Tok Pisin is startlingly sophisticated. Its vocabulary is large enough to cope with translations of the Bible and Shakespeare. And sometimes its expression is more subtle than standard English. The standard pronoun system is pretty simple, really. We have first person I (for singular) and we (for plural). Second person is you for both singular and plural. Third person is he , she or it (for singular) and they (for plural). It’s not the best of systems. You , in particular, is ambiguous. If I say I’m talking to you , it’s not possible to tell whether I’m addressing one person or several.

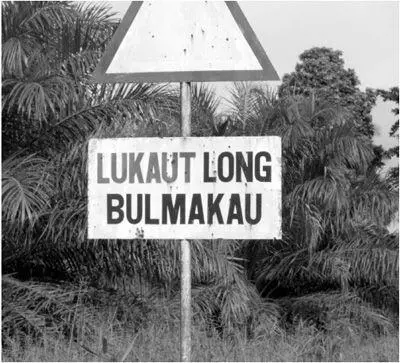

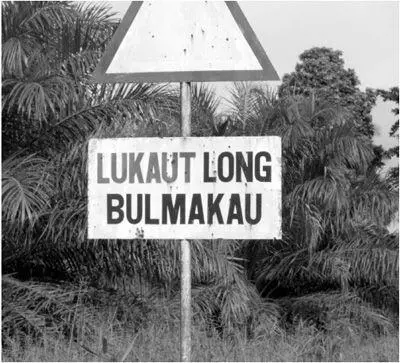

14. A sign in Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea. It reads: ‘Beware of cattle’, literally ‘look out’ + ‘for’ + ‘bull and cow’. Long is a general-purpose preposition with functions expressing such notions as ‘in’, ‘of’, and ‘on’. It’s a shortened form of belong. When Prince Charles visited Papua New Guinea in 1966 he was described locally as nambawan pikinini bilong misis kwin (‘the number one child of Mrs Queen’). Princess Anne, correspondingly, was the nambawan gel (‘girl’) pikinini bilong misis kwin .

Tok Pisin does much better. It has four different ways of saying ‘you’. Yu , on its own, means I’m talking to one person. If I’m talking to two people, I say yutupela (‘you two’). If I’m talking to three people, I say yutripela (‘you three’). And if I’m talking to more than three people, I say yupela .

The same system operates for the third person. If I say em , I mean ‘he, she or it’. If I say tupela , I mean ‘they two’. Tripela means ‘they three’. And ol means ‘they four or more’.

The first person is even more sophisticated, as, in addition to mi (‘I’), Tok Pisin allows speakers to distinguish how many people are included in the conversation. Imagine John and Mary talking to a group. John says, ‘We’re going to be late’. Does he mean ‘Mary and I are going to be late’ or ‘All of us are going to be late’? In English, it isn’t possible to decide without further exploration. In Tok Pisin, however, the distinction is clear. If John meant ‘one of you and me’, he would say yumitupela . If he meant ‘two of you and me’, he would say yumitripela . And if he meant ‘all of you and me’, he would say yumipela .

But he could do something else. He could also say, addressing Mary, mitupela , which would mean ‘he or she and me, but not you’. If he said mitripela , it would mean ‘both of them and me, but not you’. And if he said mipela , he would mean ‘all of them and me, but not you’. Here he is excluding Mary, whereas with the examples in the previous paragraph he was including her. Standard English has nothing like this. All it has is the highly ambiguous we .

The vocabulary of the pidgin Englishes of the world contain tens of thousands of words. Many have a spelling which shows a clear link with the source language, such as kap (‘cup’) and galas (‘glass’). Other words are more difficult to interpret, such as liklik (‘little’) and wantaim (‘together’). Taken as a whole, along with the distinctive grammar and pronunciation, some analysts consider the differences from standard English to be so great that they think of pidgin Englishes as new languages. If they’re right, we now have an English ‘family of languages’ on earth.

70. Schmooze — a Yiddishism (19th century)

70. Schmooze — a Yiddishism (19th century)

It’s the initial two sounds that give schmooze away as a Yiddish word. English words traditionally don’t allow the sound sh to appear before a consonant. A combination of s + consonant is fine, as in spin, still and skin . But if anyone said shpin , shtill and shkin , we would think they had a speech defect — or were engaging in a bad imitation of Sean Connery.

Things changed in the late 19th century, when a new kind of loanword arrived from Yiddish. English previously had borrowed few words from this language — matzo (‘unleavened bread’) was a very early one, first recorded in 1650. But we don’t find much evidence of them in writing until the 19th century, when we get such words as kibosh (‘finishing off’, 1836), nosh (‘food’, 1873) chutzpah (‘brazen impudence’, 1892), pogrom (‘organised massacre’, 1891) — and schmooze (‘leisurely intimate chat’, 1897).

Читать дальше

69. Mipela — pidgin English (19th century)

69. Mipela — pidgin English (19th century)

70. Schmooze — a Yiddishism (19th century)

70. Schmooze — a Yiddishism (19th century)