Russell Gold

THE BOOM

How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World

To my sources of energy:

Isaiah, Joaquin, and Laura

I recognize the right and duty of this generation to develop and use the natural resources of our land; but I do not recognize the right to waste them, or to rob, by wasteful use, the generations that come after us.

—Theodore Roosevelt, speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, 1910

There is only one rule of thumb in fracturing: that there are no rules of thumb in fracturing.

—M. B. Smith and J. W. Shlyapobersky, in

Reservoir Stimulation , reference book for petroleum engineers, 2000

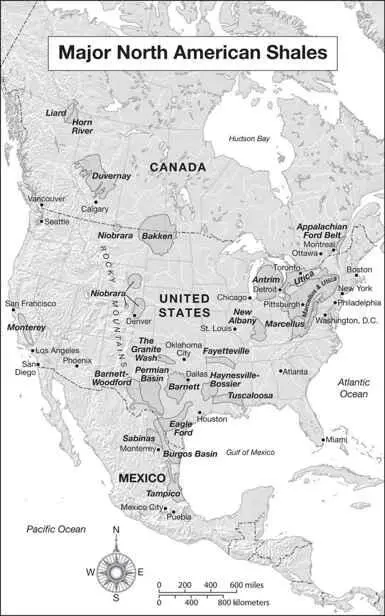

Map of Major North American Shales

1

JUST ADD WATER

A few years ago, my parents faced an unexpected choice.

Chesapeake Energy called them with an offer. The company wanted to drill for natural gas underneath 102 acres of land they owned with some friends in north central Pennsylvania. Would they be interested in signing a lease? The offer was $400,000 up front, plus royalties on any gas unearthed from the ground. It was an astounding amount of money for terrain so rocky and hilly that the local dairy farmers didn’t want it.

Despite a name that evokes sailboats and seafood, Chesapeake hails from landlocked Oklahoma City. Once little more than a two-person partnership, it grew to drill more wells than any other company in the world. At its peak, it held leases to punch holes in an area the size of Kentucky. Its annual budget topped $20 billion in 2012, and it spent a chunk of that on a sophisticated advertising campaign that preaches the gospel of domestic energy production and attempts to calm fears about hydraulic fracturing. Chesapeake drills more than a thousand wells every year and fracks each one. Once the bit churns through the dense rock, the company pumps in millions of gallons of water and chemicals to create a network of sinewy fractures, each one an escape route for trapped hydrocarbons. Gas and oil freed from the shale flows out of the cracks and up the well. The recipe that Chesapeake said it was following was quite simple: just add water. The reality, however, was more complex.

My parents’ property was valuable to Chesapeake because it sits atop one of the largest shale formations in the world. The Marcellus Shale was once so obscure that it appeared in only the most detailed geologic maps of the area. The charcoal gray rock runs from New York, crosses Pennsylvania, and stretches into Ohio and West Virginia. Near the Farm, as we call the property, it is more than a mile deep. Over millennia, the shale cooked at just the right temperature and pressure to turn long-dead microorganisms into trillions of cubic feet of natural gas. Chesapeake wanted to extract the gas and sell it to households and power plants. Sometime in the future, when my parents turn on their stove or television in Philadelphia, about 180 miles to the southeast, some of that energy might have begun its journey a mile beneath their property.

The size of Chesapeake’s offer shocked my parents, but not me. I was then—and still am—an energy reporter for the Wall Street Journal . In the mid-2000s, my beat was the “independents,” a group of midsized companies that didn’t sell gasoline or operate refineries. They drilled for oil and gas in the United States. A scrappy bunch, they were the descendants of the industry’s wildcatter heritage. They didn’t have the money and engineering muscle to compete with globe-straddling energy titans such as Chevron and BP for giant projects in the Middle East or deepwater exploration off the African coast. The independents fed on the table scraps of the energy feast.

But the picked-over United States held a surprise. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, little-known independents had figured out a way to get natural gas from dense slabs of buried shale rock. I reported on this new phenomenon and wrote the first national newspaper articles about the gas around Fort Worth in the geologic formation known as the Barnett Shale. I watched the transformation of the suburbs, as Little League fields turned into tawny rectangular drilling pads. I had a front-row seat as this energy upheaval ranged from Texas to Arkansas and Oklahoma and then vaulted to North Dakota and Pennsylvania. Using fracking, the independents found an unbelievable amount of gas—and then oil as well. Early optimistic estimates of how much was available turned out to be absurdly conservative. Even Exxon Mobil, the embodiment of the modern energy behemoth, began to look for a way to get involved.

Not long before the energy industry beat a path to my parents’ doorstep, I traveled to Pittsburgh to write an article about the leasing and drilling in southwestern Pennsylvania. This early drilling took place hundreds of miles away from the Farm. Fracking was spreading farther and faster than I had realized.

My parents and their friends bought the Farm in 1973 and built a small house. It was a place to get away from Philadelphia for a weekend, a couple hours up the Pennsylvania Turnpike but a world away from their brick row house and busy city life. Back in the 1970s, they were immersed in the left-wing, antiwar politics of the day. For the first few years, they called the property Oriente, after the Cuban province where Fidel Castro and Ernesto “Che” Guevara began their revolution. From their first days as landowners, these urbanites stood out in this conservative and poor part of the state. While their neighbors in Sullivan County worked long hours to wring a living from their acres, the white-collared Philadelphians kept their land untouched. Making money from the land wasn’t in the plan.

The trust documents reflect their vision. There were eight owners. Each owner, or couple if married, would pay an equal share. If a couple wanted to sell their share, they wouldn’t profit. They would get back the money they put in to buy the property and anything paid over the years for taxes and upkeep. Drafting the trust in an era of antigovernment protests, they figured, when the revolution came in the United States, they could always escape from the chaos to rural Pennsylvania. In the more likely scenario, in their minds, of a government crackdown on radical dissidents, the house could be a way station on the way to exile in Canada. And if none of this Armageddon came to pass, it would be a place for inexpensive vacations, where their city kids would have a chance to run around the woods and swim in a pond.

That anyone would want to drill wells on the land in search of natural gas was beyond the realm of imagination. This wasn’t Texas. When my mother called me to discuss the offer, she wanted to know what I thought. Should they sign the lease? It is a complex question, and answering it requires weighing sacrifice and opportunity, money and the environment. As a reporter, I spend my working hours talking to people who work in the industry and live near its wells. I think about how much energy the world consumes and where it comes from. There are no easy answers to the energy puzzle. There are unforeseen costs and necessary evils.

What the independents set in motion has changed an entire global industry and upended the traditional energy order. The emergence of vast, untapped energy stores, literally under our feet, allows natural gas to challenge coal and nuclear power as the dominant fuel used to make electricity. It opens the door for renewable energy to emerge as a force in its own right. But it also extends the age of fossil fuels for decades, a profound challenge to the climate. The revolution had come, after all, but it wasn’t the one my parents feared in the 1970s. It also wasn’t in Philadelphia. It was on the Farm in Pennsylvania, and in metropolitan Fort Worth, northern Louisiana, frigid North Dakota, and rural Ohio. The revolutionaries also weren’t disaffected Philadelphians, they were geologists and petroleum engineers from Texas A&M University.

Читать дальше