This, then, is a travelogue through a land obscured by smog and transformed by cranes; one that examines how rural environments are being affected by mass urban consumption. What are we losing and how? Where are the consequences? Can we fix them? It projects mankind’s modern development on a Chinese screen.

Though the chapters progress through regions and themes, the structure is polemical rather than geographic. When I had to choose between a strong case study and a line on the map, I opted for the former even if that occasionally meant leapfrogging provinces, returning to some places twice, and cutting across boundaries. Lest anyone fear that I am asserting a new territorial claim by Dongbei on Inner Mongolia, or by the southeast on Chongqing, I should state their place in these pages is determined by the powerful trends they illustrate. Similarly, my apologies to anyone who feels slighted or frustrated by my selective approach. Omission of a province is not intended to dismiss its importance any more than inclusion is meant to indicate a paradigm case.

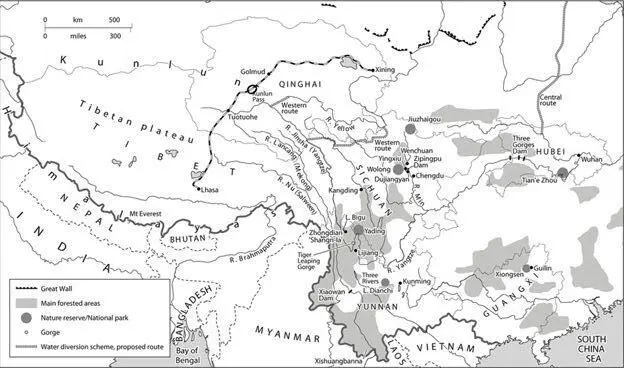

The choice of location and topics in these pages is determined purely by my own experience. Even over many years and miles, that is limited. China is simply too vast and changing too fast to capture in its entirety. Starting from the world’s high, wild places and descending into the crowded polluted plains, the book tracks mankind’s modern development and my own growing realization: now China has jumped, we must all rebalance our lives.

SOUTHWEST

Nature

1. Useless Trees

Shangri-La

A man with a beard is respected. The same applies to mountains. A person with a beard and hair is like a mountain covered with forest and grass. In the same vein, a mountain sheltered in forest and grass is like a person well clothed. A barren mountain is no different from a naked person, exposing its flesh and bone. An unsheltered mountain with poor soil painfully resembles a penniless and rugged man.

—Inscription on monument found in Yunnan, dated 1714 1

Paradise is no longer lost. According to the Chinese government, Shangri-La can be found at 28° north latitude, 99° east longitude, and an elevation of 3,300 meters at the foot of the Himalayas in northwest Yunnan Province. I started my journey at this self-proclaimed mountain idyll with the intention of working my way down and across China, tracking the progress of development on the way. Shangri-La seemed a fitting place to begin. Environmentalists considered it pristine, economists thought it backward. I planned to search here for natural and philosophical ideals, for untouched origins. But I may have arrived too late. Bumping along a dirt road through the mountains, I spied muddy hovels and forests spoiled by the blackened aftermath of logging teams. Gray drizzle doused a blaze of purple azaleas and white rhododendron shrubs. A track cut through a field of flowers to an alpine pool scarred on one side by the stumps of dozens of felled trees. The landscape, once one of the most stunning in China, had been violated.

For millennia, Bigu Lake in the heart of the region was protected by its remoteness. Although worshipped by local Tibetan communities, it was not mentioned in the extensive canons of Chinese literature. Government administrators and poetic wanderers rarely made it this far. It was too poor, too little known, too difficult to exploit.

All that changed in December 2001, when the Chinese authorities found a new way to sell northwest Yunnan’s beauty: they renamed the region Shangri-La. As well as being a brilliant piece of marketing, the appropriation of a fictional Utopia dreamed up seventy years earlier on the other side of the world was a remarkable act of chutzpah for a government that was, in theory at least, communist, atheist, and scientifically oriented.

The tourist trickle quickly became a flood. Road builders, dam makers, and hotel operators added to the height of the swell. Beauty was marketed as fantasy, often with disastrous consequences. When the Oscar-nominated filmmaker Chen Kaige wanted a spectacular location for a new kung fu blockbuster, The Promise, he came to Bigu Lake and completely reconfigured the idyllic landscape. With the enthusiastic support of the local government, the director’s team built a road through the field of azaleas, drove 100 piles into the lake for a bridge, and erected a five-story “Flower House” for the love scenes. Nobody took responsibility for the consequences. 2After he ended shooting, the concrete-and-timber house was left dilapidated; the ground was strewn with plastic bags, polystyrene lunch boxes, and wine bottles. The lake was split in half by a bridge nobody needed. A temporary toilet and road besmirched the landscape, and locals demanded compensation for sheep that choked to death on the refuse.

I had come with one of the environmental activists who exposed the scandal and forced a cleanup. Zeren Pingcuo was a thickset Tibetan who worked as a nature photographer and conservationist. He was a man of few words, but what he said was usually to the point.

“Sacred places are no longer sacred,” he said, showing me before-and-after pictures of development in which lakesides and pastureland quickly filled with tourists, cars, and hotels.

He showed me older pictures of his Himalayan home: breathtaking scenes of hillsides decked with azaleas in spring, lush green valleys in summer, a forest in glorious autumn reds and golds, and mountain snowscapes in winter. There were intimate portraits of Naxi children and Tibetan monks, and lively scenes from monasteries, markets, and festivals. That idyll had first been disturbed in the eighties and nineties by logging teams, then by tourism.

As our car climbed the steep mountain road, the destruction became more evident. Vast tracts of spruce forest were chopped and burned. The hillsides were filled with the blackened, stumpy corpses of trees and the withered brown saplings that were supposed to replace them but had failed to take.

“This all used to be virgin forest, but now it is an ecological war zone,” said Zeren. “The timber companies came here and cleared the hillsides.”

His home village of Jisha, which nestled in a high mountain valley, was suffering the results. He explained: “With less forest cover, there are fewer birds. With fewer birds there are more insects. And more insects means more damage to the crops.”

Although many locals believed their home was Shambala—a form of heaven on earth—Zeren was no romantic about the past. Before development, life for locals was tough and often short. But, even among his own people, the long-term trends disturbed him.

“Tibetans have lived in harmony with nature for hundreds of years. But now we consume in a decade what we used to use in a century.”

I too was here to get a taste of Shangri-La, albeit for work. I had come to look at beliefs. At the time, commentators in China complained their nation was mired in a grimy materialist mind-set that lacked an ideal of what a better world might look like. I wanted to see the alternatives. In such a diverse nation there were many: Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, nature worship, romantic escapism, and political utopianism. Shangri-La seemed as good a place as any to start.

But as I soon came to realize, searching for paradise was a complicated business, particularly when there were furiously competing claims to be the “real” Shangri-La. The word first appeared in the 1933 fantasy Lost Horizon by the British novelist James Hilton. After a crash landing on the Tibetan Plateau, the Western survivors stumble across the idyll of Shangri-La:

Читать дальше