Not all teenage sexual behavior derives from self-harm. Ideally, in fact, none of it would. Sexual curiosity and experimentation is a perfectly natural part of growing up. Girls have just as much sexual desire and curiosity as boys. They are curious about their genitals and others’ as children. They masturbate. The hormones that race through a teenage girls’ body create just as much sexual feeling as boys’ hormones do.

Psychological discussions about why girls might engage in sexual activity, however, do not include any information about girls’ sexual desire. Michelle Fine refers to this as “the missing discourse of desire” in her article of the same name. {7} 7 7. Michelle Fine, “Sexuality, Schooling, and Adolescent Females: The Missing Discourse of Desire,” Harvard Educational Review 58, no. 1 (1988): 29–53.

She notes that we talk about victimization, violence, and morality, but we almost never examine the fact that girls, too, have desire. In fact, sexual desire is seen as an aberration for girls, which means that we almost always assume that girls act sexually only to fulfill their hopes for a relationship. This can certainly be the case, but it’s potentially dangerous—as we make policy, as we aim to help girls, as we aim to help ourselves—not to account for the fact that they also experience sexual arousal.

We don’t generally like to say these things about adolescent girls. We don’t acknowledge that they have desire. We live in a culture that provides little space for any sort of female teenage sexual behavior, including what many would consider normal curiosity and exploration, because it makes us so uncomfortable.

How did this odd untruth about female desire arise? Ancient and medieval understandings of puberty emphasized vitality and social benefit, and they made little distinction between male and female desire. The rising influence of Christianity, though, established the beliefs that youthful sexuality was dangerous, immoral, and threatening to social order. With the Enlightenment, boys regained some freedom over their right to sexual expression, but girls’ sexual desire remained deviant. Over the following centuries, while puberty for boys took on its association with manly desire, for girls it grew more and more removed from any notion of desire and instead focused entirely on preparation for reproduction and motherhood. {8} 8 8. Joan Jacobs Brumberg, The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls (New York: Random House, 1997). See also Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1928).

In conjunction with this, girls’ experience with puberty was associated only with the need to protect their purity so they would be ready for their fate as mothers. Our notions today about girls and female desire are built on outdated patriarchal, religious notions.

Today, the cultural narrative is as follows: boys are horny, but girls are not, and so girls must do what they can to keep boys and their out-of-control hormones at bay. We like this narrative, outdated and unscientific as it is. It keeps us safe from the notion that girls might want to be sexual as much as boys do. But , you might be thinking, what is the problem with keeping girls safe? As I explore in this book, the problem is that when you deny a group of people an essential part of who they are, a part they have full right to, they often wind up using it in a self-destructive manner rather than as a natural part of their development. In other words, if teenagers getting STDs and becoming pregnant and acting out sexually is a cultural problem, then stigmatizing teenage sex only makes it worse—much worse.

The distinction between acting on natural sexual feelings and using male attention and sex to fill emptiness is an important one. In this book, I carry the underlying assumption that teenage girls have natural sexual feelings, just like boys, and that perhaps we need to find an outlet for girls to express themselves sexually, an outlet that the girls control themselves, not the cultural expectations about who they should be as sexual creatures. I also try to demarcate what it might look like when a girl has stepped beyond cultural boundaries and has begun using male attention and sex to try to feel worthwhile. And there is a difference: some girls manage to cope with our culture’s lack of space for girls to have sexual feelings, but others struggle and tend to use sexual attention and behavior to harm themselves emotionally. So for the purposes of this book, I refer to self-destructive sexual behavior as promiscuity and to the girls who pursue such self-destructive attention as loose girls.

Without discussion, without creating the space for girls to talk about their sexual experiences, we are left with assumptions that are almost invariably wrong. If we are not virgins, we are called sluts. We get what we deserve and what we wanted. Or—and this emerging view is not as positive as it seems—we are empowered by our sexuality; we are waving our flags of sexual freedom. After all, in this day and age, to suggest that a girl having sex is anything other than empowered and strong is antifeminist.

Meanwhile, the media continues to propagate the double-edged sword, the messages that girls have always received. You must be sexy, but you may not have sex. You must make men want you, but you may not use that to fill your own desires. The women’s studies professor Hugo Schwyzer calls this the Paris paradox, based on Paris Hilton’s comment that she was “sexy but not sexual.” {9} 9 9. Hugo Schwyzer, “The Paris Paradox: How Sexualization Replaces Opportunity with Obligation,” Hugo Schwyzer Blog , www.hugoschwyzer.net , November 9, 2010, hugoschwyzer.net/2010/11/09/the-paris-paradox-how-sexualization-replaces-opportunity-with-obligation/ .

He notes that young women raised with Paris Hilton in the limelight were promised sexual freedom but wound up with more obligation than abandon. In other words, girls’ requirement to be sexy greatly outweighs any attention to what might be a natural, authentic sense of their sexual identity.

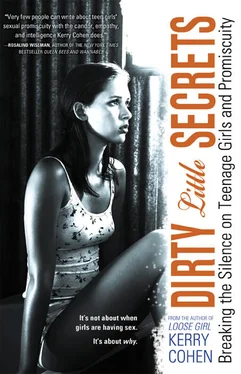

This is not a book telling teenage girls not to have sex. On the flip side, it’s also not a book that encourages promiscuity. It’s a book about how we can all work together to find a way to let teenage girls stop harming themselves with their sexual behavior. It’s a book—at its core—about girls’ rights and sexual freedom.

The true experience of being a teenage girl these days is so lost inside all this noise, all the assumptions and messages coming from everyone but the girl herself, that we couldn’t possibly know what emotions are behind promiscuous behavior. That’s why I went straight to the source—finally—and asked to hear from the girls and women themselves.

I interviewed approximately seventy-five American volunteers who had originally emailed me after reading Loose Girl . {10} 10 10. Volunteers completed a survey that read simply, “Describe your loose girl experience.” All volunteers answered my request after having read Loose Girl or having become aware of it and its theme.

I do not claim by any stretch of the imagination to present scientific findings. These are qualitative stories from real girls who believed in this project and understood that by sharing their stories they could potentially help other girls out there who struggle with similar feelings and behaviors. Some are still teenagers, but others are older and either still act out or have learned to stop. These girls come from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Most are white, but about 15 percent are black, Asian American, Hispanic, and biracial. Some call their mothers their best friends. Some have never met their fathers. Some have happily married parents and eat dinner with their families at the same time each night. Some have been raped. Some got pregnant. Some have been treated for STDs. All of them have carried shame about their behavior at one time or another, and all of them have felt alone. Not one felt there were any guidelines out there to help them move out of this behavior. This book answers that need.

Читать дальше