Sebastian Gorka - Why We Fight - Why We Fight - Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sebastian Gorka - Why We Fight - Why We Fight - Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Washington, Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Regnery Publishing, Жанр: Политика, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Regnery Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- Город:Washington

- ISBN:978-1-62157-640-2

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

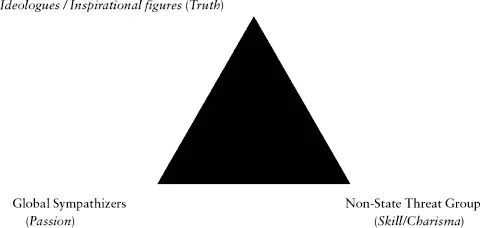

Likewise, in an irregular army, the role of the military commander is not filled by a professional warrior subordinated to a political elite. Osama bin Laden was a self-taught warrior, a mujahid who never spent time at a war college or wore the uniform of a national army. Al-Qaeda’s current leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was a medical doctor. His skill as a jihadi leader is not measured solely in terms that concerned Clausewitz, namely, prowess on the battlefield. Rather, he must be understood in non-military terms as an ideologue in his own right, an “information warrior” who inspires by personal example. The commander of the Clausewitzian trinity was judged by his ability to prevail despite the “friction” and “fog of war.” Today’s jihadist leaders, such as the head of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and jihadi operatives, such as the San Bernardino killers, are measured less by their success on the battlefield—minimal since 9/11—than by their “authenticity” as “true believers” and their ability to inspire others. Each is an example of a “holy warrior” prepared to die not for a political end state, but for a transcendental truth, judged by his capacity to inspire other violent non-state actors.

Finally, the passion and hatred-driven third part of Clausewitz’s trinity must be redefined. No longer is the enemy limited by his national population. ISIS, like the Muslim Brotherhood, is not constrained by its ability to rally the citizens of a particular nation to the cause of war or by their willingness to be drafted into a national army. The enemy’s recruiting pool is not based on a nation-state—it is global. Irregular warriors may be recruited from Algeria, Somalia, or Michigan. The population from which ISIS draws warriors is not territorially bound, but religiously defined by the idea of the ummah , or the global Islamic community. And in this, ISIS is not alone. The new anti-capitalist extremists and anarchists such as Antifa are also unrestricted in their mobilization by national borders. Consequently, although reports of the death of the nation-state may have been greatly exaggerated, a definition of war that pertains only to nations is indeed dead. Clausewitz’s trinity still applies to state-on-state conventional war, but it must be supplemented with another trinity that can depict the types of actors our troops are already fighting.

Clausewitz’s trinity divided the world into three parts: the government, the governed, and the defenders of the state. Each reflected a different characteristic: reason, passion, or skill. Although the triangular representation of the three implies equality, it is clear from On War that Clausewitz privileges the military, or more specifically, the artful commander, who harnesses the population’s passion and might so the nation may realize its goals.

Today’s irregular enemy should be understood as more egalitarian. Just as the media have been democratized, with websites and blogs turning consumers into producers and vice versa, the trinity of the irregular enemy affords and invites an interchangeability of roles and functions. Leaders can be fighters, followers can become leaders, and both can interpret and feed into the enemy’s understanding of why force is necessary and what ultimate purpose it serves. In other words, the components of the Clausewitzian trinity have become utterly fluid and interchangeable.

This has profound implications for the resources the enemy can mobilize against us. We are faced by an Arab terrorist as the leader of ISIS, but the violence carried out in the name of the “truth” that he serves can be executed by a Nigerian “underwear bomber” on a commercial airliner or by an Uzbek terrorist turning his truck into a lethal weapon on a Manhattan bicycle path. There are no limits to who can be recruited and deployed against us. The only requirement is that they subscribe to the religious ideology that is global jihad, or to the next totalitarian belief system that justifies violence against anyone who disagrees with its adherents.

A second implication is that in the wars America fights today, national interest no longer governs the enemy’s use of force. Rather, it is a truth defined not by a governing elite, but by ancient religious texts or the interpretations thereof by ideologues with both political and otherworldly motivations. Clausewitzian raison d’état , the objective of violence, is no longer bound by cold or technical definitions of national interest. If ultimate approval is promised to the religious or utopian suicide bomber or mass killer, then US national security elites must not assume that the rationale for violence is subject to the limitations of a Westphalian framework of analysis. In today’s irregular warfare, therefore, we can replace the rationale of the trinity with the transcendental end that the true believers see themselves as serving.

Finally, in the new threat environment, the third actor of the Clausewitzian trinity—the commander and his forces—is radically redefined. During the early twentieth century and later during the Cold War, practitioners of irregular warfare had one very Westphalian goal: although they were not representatives of nation-states, they sought to seize state power. This is how the master of this kind of warfare, Mao Zedong, revolutionized our understanding of the utility of force. No longer was it strategically employed to serve an established government. Instead, by skillfully conducting multifaceted campaigns on diverse lines of effort, the insurgent could systematically build a “counterstate”—a shadow government that, when powerful enough, could challenge the incumbent in a conventional campaign, destroy it, and then become the new state itself. This is exactly what Mao accomplished in China with his “People’s War,” which broadened our understanding of warfare. But he also reinforced the Westphalian context since the goal of the insurgent was always to become the new nation-state.

Today, in contrast, we face a foe who rejects the state-centered Westphalian model, an enemy who is not interested in a war of self-determination in the classic sense of postcolonial independence. Instead, groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda fight for worldwide religious supremacy. Their idea of self-determination is tied not to the nation-state, but to a global theocracy, the Caliphate, within which all shall be subject to the will of Allah and not the will of the people.

It is likewise clear that the last element of Clausewitz’s trinity must be reassessed in the case of an irregular threat group that is even more ambitious than Maoist People’s War would have us expect. We cannot represent today’s global jihadi movement as a nation-state military led by a commander serving national interests. This third part of the trinity is now populated by various types of actors. It consists of leaders such as al-Baghdadi or Zawahiri, who say they serve no government, only God. It also refers to domestic enemies such as Mohammad Sidique Khan, the British terrorist who masterminded the 7/7 London attacks. And lastly, it can also refer to the likes of Anwar al-Awlaki, the Yemen-based American Muslim cleric who may not have had classic command and control of Major Nidal Malik Hassan, the Fort Hood shooter, or Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the Nigerian “underwear bomber,” but far more importantly acted as inspiration and sanctioning authority for both men and continues to inspire new jihadis from beyond the grave with lectures and videos that are still circulating around the globe.

Clausewitz is still valuable. His understanding of what war between states should look like has not changed with the arrival of a globally motivated and capable non-state actor using irregular tactics and strategies. Nevertheless, his trinity cannot be applied directly to such enemies. The context has changed. The world can no longer be described as consisting solely of the governed, the governing, and the regular militaries that serve them. It has become more variegated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Why We Fight: Why We Fight: Defeating America's Enemies - With No Apologies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.