This is one reason why Western counter-propaganda now targets not so much Russians in Russia itself as Russian speakers in the neighboring states, primarily the Baltic countries and Ukraine. The aim is to prevent them from becoming Russia’s “fifth column” on the Western side of the new divide cutting through Europe. This is realistic: the paradox of the common information space is that the media environment in a given area is usually dominated by the prevailing local narrative.

Use of Western soft power

There are few illusions in the West that it can influence Russian domestic politics from the outside. This is not just the result of the measures taken by Putin and his supporters beginning in 2012, such as the law which branded foreign-funded NGOs “foreign agents.” The Russian elites, for all their wealth and familiarity with the West, are anything but pro-Western in their attitudes, outlook and ambitions. They are also closely tied to the Kremlin, with relatively few defectors. The Russian middle class is relatively small – even in happier times its share of the population was between 15 and 20 percent – and is currently shrinking, hard hit by the crisis. Much of it, moreover, is composed of government officials loyal to the state. The bulk of the Russian population at large – around two-thirds – are staunch Putin supporters. After Crimea, this fan club has swelled by another 20 percent. The pro-Western liberals, many of whom are strongly anti-Putin, are too few and far between, largely disunited and demoralized and, crucially, out of touch with the common people.

The hope of some in the West is that, in the war of values, soft power is their greatest asset. This soft power is most effective when it comes to such issues as peace and prosperity, affluence, prospects of a better future for the next generation, and the general quality of life. However, soft power is much more effective in attracting the more mobile elements in Russian society to emigrate to Europe or North America than in motivating the Russian people in Russia itself to embrace and practice Western values, not to speak of supporting Western policies. Even as the Russian people seek to deal with corruption, lawlessness, arbitrariness, rights abuse and monopolies of various sorts, it is not a given, to put it mildly, that a Russia which shares more values with Western countries will also align its interests with those of the United States or the EU.

Cooperation within confrontation

Western leaders recognize, of course, that it is wrong to see Russia only as a threat. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, having taken a tough stance on Russian violations of the post-Cold War “peace order” in Europe, never stopped reminding others that fixing and maintaining security in Europe required cooperation, even partnership, with Russia. Berlin made it clear that it wanted the implementation of the Minsk II agreement as a prerequisite for normalizing relations between Germany and Russia. France’s François Hollande and other EU leaders also subscribe to that view.

For the United States, the geopolitical importance of Ukraine was never too high, and it waned when the armed conflict there abated. Washington, however, needed Moscow’s assistance in 2015 to complete the nuclear deal with Iran, which – to the surprise of the White House – did not fall victim to the Ukraine crisis raging at the time. After Iran, the US needed Russia to try to reach a political settlement in Syria, and a degree of cooperation became possible. North Korea’s experimentation with thermonuclear weapons also puts a premium on US–Russian collaboration.

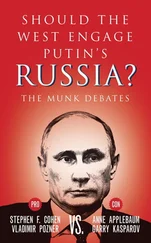

To those fearful of Russia, these elements of cooperation constitute “appeasement” or even amount to a “betrayal” of a principled Western stance. In reality, national interests continue to prevail. The United States and the EU countries will reach out to Russia when they have to – and when they believe that the degree of commonality of interest is sufficient to expect productive collaboration. This, however, does not represent either appeasement or betrayal. Contemporary Western–Russian relations are highly competitive on account of the fundamental clash of interests regarding the global and regional order, and any cooperation between the parties will happen within the wider environment of continued confrontation.

US and EU responses to the Russian challenge suggest that they regard the challenge as real but moderate, manageable primarily by economic means. This may appear reasonable, but it misses the central issue: if the sanctions and other measures fail to bring Russia back into line, how then should the West relate to a major power which rejects the Western-dominated order and shares that attitude with other even more powerful non-Western countries.

4

Navigating the New Normal

To begin with, one needs to recognize that, as time goes by, the West’s challenges related to Russia are not going away or getting smaller. A stronger Russia, should it emerge, will be a stronger challenger; but a weaker and, particularly, a failing Russia will be an even more formidable challenge to deal with. One also needs from the start to drop any residual illusions about a Russia somehow reassociated with the West and more or less following its lead. That window is permanently closed.

Russia looks ossified, even petrified, under the current leadership, which has been in place for over a decade and a half. Yet, it will change, either more smoothly, as a result of policies from above interacting with processes from below, or perhaps abruptly, in unexpected ways and without much prior warning, as it has done a couple of times in its modern history. However, even as Russia changes, it will be different from the West and even from its neighbors in Central Europe such as Poland. Russia will act in its own way and will not be subject to Western-designed norms and conventions in either domestic or international behavior.

Russia will continue to compete with the West. The West’s hope that Russia will inevitably succumb to the pressure of economic factors, such as the low oil price and economic sanctions, resulting also in the lack of investment and a ban on technology transfers, is so far just a hope. Even if Russia continues on a downward path, this descent may be long and will not necessarily lead to a friendlier policy vis-à-vis the West. The opposite is at least as likely. Pro-Western political and social forces within Russia are at their weakest in decades. Popular Russian nationalism defines itself as frankly anti-Western.

Competition and rivalry is not all there is to the West’s relationship with Russia. There are compelling reasons for cooperation in a few selected areas. As already mentioned, in the field of WMD non-proliferation, Moscow has continued to interact productively with Washington and others on Iran and North Korea, despite the general atmosphere of US–Russian confrontation. In Syria, Russia is key to the future political and military developments.

Over time, Russia may have to become more involved in Afghanistan and Central Asia in order to oppose armed radicals there. Up to a point, its interests will be aligned with those of the West. With Islamist extremism a rising threat to Russia itself, Moscow will continue to fight terrorism both within its own borders and internationally. The transnational nature of contemporary terrorism makes Moscow a valuable partner to Western governments, whatever they think about Putin or his regime.

Thus, Russia in the foreseeable future will be primarily a competitor but may also occasionally – and within the general environment of competition – be a partner of the West. Under the present politico-economic system, it is likely to continue on a declining trajectory, but its military power will grow for the time being. This unequal mix of competition and cooperation, economic decline and military expansion, will make crafting a Western policy toward Russia a particularly difficult task. This task can be divided into elements, each with its own time horizon.

Читать дальше