The vinchuca species most largely responsible for chagasic transmission in Bolivia is Triatoma infestans, which is relatively non-aggressive and whose bite is more annoying than it is painful. Consequently, Bolivians do not refer to the insects as “assassin bugs,” as they are called in the U.S., but as “ vinchucas, ” from the Quechua word huinchicuy, which means something that falls rapidly, because they glide down from the rafters, and as “kissing bugs,” because they prefer to suck blood from the faceoften from the lips and from near the eyes. Although Triatoma infestans has thus avoided the name “assassin bug” for the more benign name “kissing bug,” there is the subtle irony that the “kiss” of the bug can lead to death.

Epidemiology of Chagas’ Disease in Bolivia

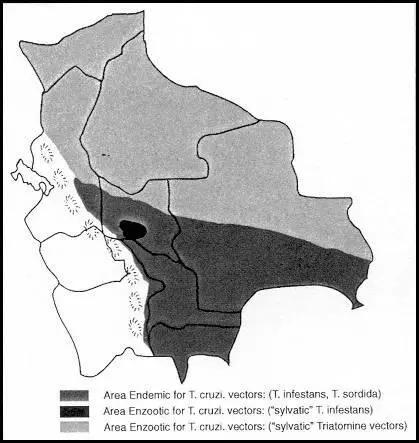

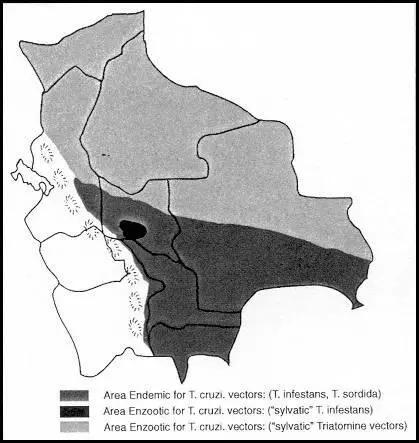

In Bolivia, estimates are that one in five (1.5 million people) of the total population (7.3 million) have Chagas’ disease, and that half the population live in endemic areas of the disease (SOH/CCH 1994; see Figure 13). An earlier epidemiological survey of Chagas’ disease was carried out in 1978 in Pongo, a village situated eleven miles from Santa Cruz, capital of the tropical oriental plains (De Muynck et al. 1978). Researchers examined the infection rate of houses by triatomines; the infection rate of the triatomines by T. cruzi; the infection rate of human, canine, and feline populations; cardiac and digestive morbidity; and the construction of houses. Some 26 percent of the houses were infested with T. infestans, 53 percent of the humans were found infected with T. cruzi; and 23 percent of the dogs and 7 percent of the cats were also infected. Some 7 percent of those older than five years showed electrocardiogram signs compatible with chagasic myocardiopathy, and 2 percent had an elevated risk for sudden death as a consequence of their chagasic heart disease. More recent studies have found similar results throughout many rural areas in Bolivia (Valencia 1990a, 1990b; see Appendix 5).

The incidence of disease is highest in rural areas, where 42 percent of the people live and where poverty, lack of education, and poor housing facilitate infestation by vinchucas. The average rural income per year is $580, the illiteracy rate is 50 percent, and the fertility index is 6.1 per mother (1992 census). Forty to eighty percent of rural people are infected with T. cruzi, and 38-78 percent of the homes are infested with T. infestans. Over 30 percent of the insect vectors captured in and around rural houses are infected with T. cruzi. These areas are generally those lived in by the indigenous population (60 percent of the population) and to a lesser extent by the mestizo population (25 percent) and those of European descent (15 percent). Some ethnic communities are seriously debilitated by Chagas’ disease, and their survival and well-being can be seen as a race against T. cruzi.

Cardiac morbidity due to chronic Chagas’ disease is high in rural communities of Bolivia. According to one study in a community in the central Andes, sixty-nine of 104 persons (66 percent) tested positive to T. cruzi by two serological methods (Weinke et al. 1988). Twenty-one of the sixty-nine people (30 percent) showed modest and severe cardiac abnormalities. This community had a high percentage (56 percent) of houses infested with Triatoma infestans infected with T. cruzi. Epidemiologically, there was a significant relationship between substandard housing, infested houses, and cardiac morbidity.

Figure 13.

Areas endemic for T. cruzi in Bolivia. (See Appendices 5 and 7.)

Seven children in Bolivia die each day from the acute phase of Chagas’ disease, which leads to meningoencephalitis (Ault et al. 1992:9). Estimates throughout Latin America are that 10 percent of children with acute infection die from the disease (Manson-Bahr and Bell 1987:80). Treatment of acute Chagas’ disease is important to lessen the severity of symptoms and prevent death. Chemotherapy has decreased the mortality rate from about 50 percent in 1900 to 10 percent currently (see Appendix 13).

The majority of new infections of Chagas’ disease are found in children from only a few weeks of age to two years of age. Bolivian children are more vulnerable than adults to acute forms because they have developing immune systems and often have other diseases and are malnourished. The immaturity of the immune system in the fetus and the child partially explains the appearance of cerebral involvement of the disease almost exclusively at these times (Moya 1994). [14] 1. Meningoencephalitis due to T. cruzi has been reported in pharmacologically immunodepressed patients and in patients with AIDS (Jost et al. 1977; Corona et al. 1988; Del Castillo et al. 1990). (See Appendix II.)

With adults, the acute phase occurs in roughly 25 percent of people infected with T. cruzi, and a much lower percentage of that number die than among infants. The lesser occurrence of the acute phase in adults presents a problem for those treating the disease in that the victims are frequently unaware of having Chagas’ disease and go untreated until the incurable chronic phase, when the symptoms frequently are not attributed to T. cruzi. Thus the age of the victim is important in the epidemiology and treatment of Chagas’ disease (WHO 1991:2).

Some generalized symptoms of the acute phase are fever, enlarged liver and spleen, generalized edema, and swollen lymph nodes (WHO 1991). Symptoms can be sudden and dramatic, as a person may suffer from moment to moment with fever, chills, coughing, diarrhea, dysphagia, tachycardia, headaches, excitation, muscle pains, lack of appetite, neuropsychological alternations, exanthematous rash, and general malaise (Borda 1981; Chagas 1911; Katz, Despommier, and Gwadz 1989; Köberle 1968). Fevers range from 99.5 to 102.2 degrees Fahrenheit; temperatures above 104 degrees are rare and not indicative of the severity of infection. The fever may be continuous or recurrent, lasting four to five weeks and then falling gradually towards the normal range. Infants under one year of age frequently have higher temperatures and suffer symptoms of meningeal irritations (rigidness of neck and spinal column), convulsions, ocular seizures, stupor, and coma, which often lead to death. Coughing is caused by bronchial irritation associated with abundant mucus secretion. Diarrhea is frequent, very obstinate, and cannot be explained either by bacterial or by parasitic intestinal infections (see Appendix 9).

One common symptom of acute Chagas’ disease is development of a chagoma, which is a local inflammatory swelling, like a large, hard boil, found frequently below the eye as well as elsewhere on the body, that lasts for weeks (Manson-Bahr and Bell 1987:80). Chagomas differ from the local swelling and edema that follow a bug bite, which resolves quickly. Chagomas result from local inflammatory swelling caused by amastigotes multiplying in fat cells. When the chagoma occurs near the eye, the eyelids become filled with liquid and one eye often becomes inflamed, which is called Romaña’s sign (see Figure 4). Carlos Chagas considered Romaña’s sign the hallmark symptom of Chagas’ disease; however, this is misleading, because it is present only in one-fourth of all acute phases, and only 25 percent of infected people suffer the acute phase. For every one hundred persons infected with T. cruzi, only six manifest Romaña’s sign. Some Bolivians think they are not infected with T. cruzi because they can’t recall having a swollen eye. Others attribute Romaña’s sign to conjunctivitis due to the dusty regions of Bolivia and seldom report it to doctors. They should be advised that if the swollen eye continues for longer than a week they should consult a doctor.

Читать дальше