Trypanosoma cruzi is as potentially destructive to human beings as is a nuclear bomb, yet it is so minuscule that it largely goes unnoticed. Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) causes what is known as American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas’ disease. The first time that I saw T. cruzi was June 6, 1991, in Cochabamba, Bolivia. I recorded the following notes:

Yesterday, I saw T. cruzi under the electronic microscope. They clustered together, like strands of tangled wool, and were wiggling violently, like so many minuscule hydra monsters, trying to break free with their tentacles and attack you. One broke free and swam toward me…

Hernan Bermudez, laboratory technician, then looked into the microscope and exclaimed “ El Asesino!” [“The Assassin!”]. I felt thrilled to be face to face with the parasite that was infecting millions of people in Latin America, that has spread so rapidly throughout Latin America, and that can multiply to millions of offspring in the human body.

The sighting of T. cruzi did not generate hatred but awe and respect. It began a lasting relationship.

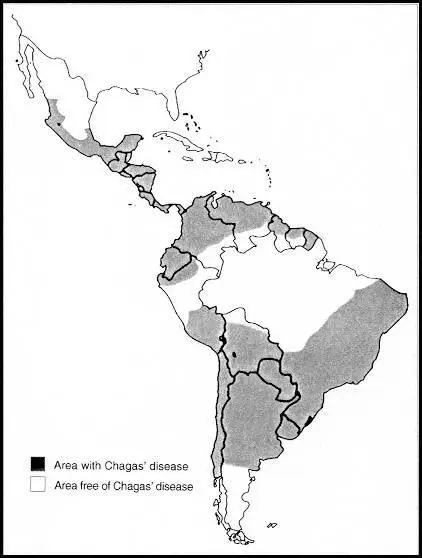

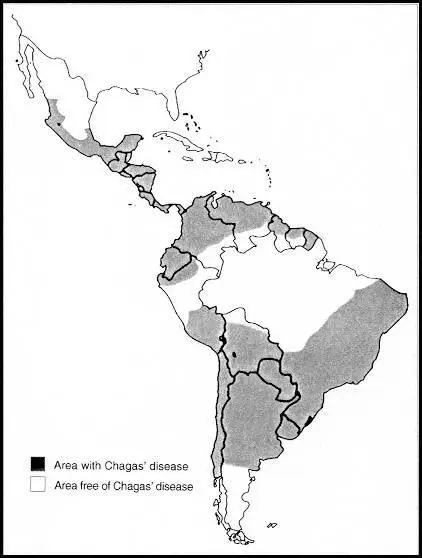

T. cruzi infects 18 million people in Latin America and is the major public health problem for development in Latin America, because it debilitates and kills adults during their prime of life (World Health Organization 1985, 1991, 1994, 1996). The Pan American Health Organization has identified Chagas’ disease as the most important parasitic disease in Latin America and the major cause of myocardial illness (PAHO 1984). This flagellate protozoan parasite travels to humans through the bite of triatomine bugs—a particular order of sucking insects—entering neuron tissues of the heart and other organs and causing irreversible cardiac and gastrointestinal tract lesions in 30 to 40 percent of the cases. T. cruzi migrates by means of infected bugs, animals, humans, blood transfusions, and organ transplants. Currently, there is no cure for the chronic stage of Chagas’ disease, but T. cruzi can be controlled through improved housing and hygiene. Named after Carlos Chagas, who discovered T. cruzi in Brazil in 1909, Chagas’ disease has spread throughout Latin America and the Southwestern United States (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of Chagas’ disease in Latin America. Although it is still difficult to form an accurate picture of the geographic distribution and prevalence of Chagas’ disease, among an estimated total population in the endemic countries of 360 million people (excluding Mexico and Nicaragua, for which adequate data are not available), at least 90 million persons (25 percent) are at risk of infection, and from 16 to 18 million people are infected. (World Health Organization 1991:27). (See Appendices 6 and 7.)

This book concerns Chagas’ disease in Bolivia, where infection rates are higher than in any other Latin American country (SOH/CCH 1994). It shows how human beings have created environmental and social contexts for the spread of Chagas’ disease and addresses such questions as these: Can humans be as effective in eliminating such diseases as they are in promulgating them? What are successful prevention projects and what are not? What factors are necessary to design a successful intervention project? Further, it shows how Andeans have culturally adapted to the spread of the disease and illustrates why understanding cultural belief systems is critical to the success of prevention programs.

Surprisingly, many Bolivians are unaware of Chagas’ disease and rarely suspect it as the cause of death. They attribute its symptoms to other causes such as heart disease, volvulus, improper foods, and fatigue. While it is unnecessary that most individuals understand Chagas’ disease from a biomedical perspective, health educators need to translate scientific information about the disease into culturally appropriate categories that are sensitive to indigenous values, traditions, and motivations. To do this, health educators need to integrate the biomedical knowledge of Chagas’ disease with the ethnomedical practices of Andeans.

Chagas’ disease has received little attention and funding of research, treatment, and prevention measures, perhaps because of who gets itpoor, illiterate, indigenous Andean peasants. This lack of attention is also a result of the disease’s latent periods in the human body (see Figure 8). Frequently, T. cruzi lies dormant for years until manifesting itself in the critically debilitating chronic state. Peasants seldom connect bites from vinchuca bugs to heart disease, so the disease spread by the bite goes undetected at early, treatable stages.

Chagas’ latent states and mobility relate it to other slow-acting killersother epidemics and diseases that cross boundaries. Infected insects, humans, and animals allow T. cruzi to travel swiftly and to enter homes unannounced to its hosts. In this, Chagas’ disease shares certain features with other diseases, such as AIDS. It is environmentally driven, as is AIDS. Similar “new” diseases have emerged from the savannas of eastern Bolivia (Hemorrhagic Fever), the rainforests of northern Zaire (Ebola virus), a Navajo reservation in the Four Corners region of the western United States (Hantavirus), and the urban poverty of the south Bronx (see Garret 1994). Yet, Chagas’ disease is ancient. In this case, it is a parasitic disease encouraged by environmental changes that bring T. cruzi, vinchucas, and humans into close contact. Humans destroy natural animal hosts for this parasite and habitats for its vector bug. As a result, parasite and vector have moved to humans. Parallels also can be found with Lyme disease. Suburban housing developments encroach on forest areas where humans come into contact with rodents, especially white-footed deer mice. These rodents host Ixodid ticks, vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete that causes Lyme disease (see Spielman et al. 1985; Burgdorfer et al. 1985).

Our awakening to these disease agents is a challenge of the coming millennium. To catch a glimpse of diseases to come, this book details an epidemic battle in Bolivia, a seemingly remote country, and shows how to win it. It provides suggestions for community members, health workers, and social scientists on how to stop Chagas’ disease. It is also important to examine factors of the disease’s spread in Bolivia to prevent this from happening elsewhere.

Andeans have excellent ways of dealing with native diseases, but they also need anthropologists with cultural sensitivity and doctors with biomedical expertise to help them adapt to potential epidemics. These epidemics are in part phenomena of the late twentieth century. They are aided by overpopulation, massive migrations, urbanization, widespread impoverishment, destruction of the rainforests, and erosion of valuable soil, among other factors. Curtailing Chagas’ disease calls for public policy changes to stop the above practices, to increase research and international assistance, and to recognize and utilize indigenous medical systems in its control.

To what extent does a personal agenda interfere with objective research? It is difficult for medical anthropologists to espouse scientific positivism when they are studying traditional medical systems based on premises other than positivism, such as divination, spirits, balances, social relationships, and cultural continuity. Often there are no ways to prove why things work in a culture; the fact can only be noted that they do. Consequently, analyses and interpretations of medical anthropologists are personal and to some degree subjective.

Читать дальше