Empacho has all sorts of possible explanations connected to cutting oneself off from the nutritive fluids or sustenance of the environment. It is corrected by sharing a meal with the earth shrinesfor example, burning coca, llama fat, and guinea-pig blood in the sacred sites that are spread throughout the ayllu (community). The symptoms of Chagas’ disease, diffuse as they are, are read much as one would play a hand of cardsthat is, according to what is needed at the time.

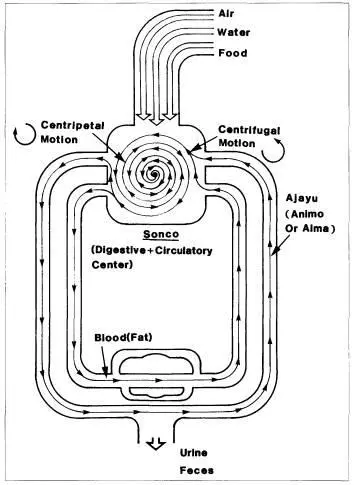

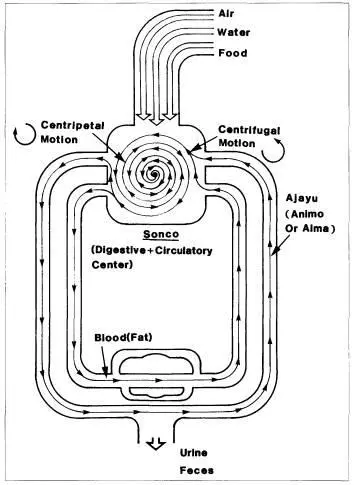

Kallawaya herbalists recommend enemas and purgatives to cure empacho, fievre, and chuyma usu, which are symptoms of Chagas’ disease but which they understand as a malfunctioning of the body’s hydraulic system rather than the intrusion of a parasite. Kallawayas conceptualize the body as a skeletal-muscular framework with openings, conduits, and processing organs. Fluids enter and are processed into other fluids. Poisons that develop from distillation must be periodically eliminated before they attain toxic levels. Illness is caused by obstructed tubes and accumulated fluids, gas, urine, feces, mucus, and sweat. Therapeutically, Kallawayas employ enemas, emetics, and sweat baths to cleanse the body of these fluids.

Figure 11.

Kallawaya ethnophysiology.

According to their ethnophysiology, megasyndromes of the esophagus, colon, and heart are interpreted by Bolivian peasants as caused by the accumulation of fluids and need to cured by emetics and purges. Megasyndromes are interpreted as the congestion of distillation processes of the chuyma the internal organs. Frequently, the only complaint of peasants stricken with T. cruzi is chuyma usu, “ my heart is sick,” quite literally, “I have a congested heart” (as well as other internal organs). The widespread practice of emetics and purges in Andean medicine for the last thousand years results from dealing with the congestions of Chagas’ disease (heart, colon, and esophageal blockages). For this reason, peasants most readily associate Chagas’ disease with empacho meaning their bodily fluids no longer circulate from within the body to the outside but are locked into a centripetal movement. In educating Andeans about Chagas’ disease, a comparison can be made with the parasitic relationship of T. cruzi to triatomines, animals, and humans in that this microorganism flows in and out of the body in what could be called centripetal and centrifugal motion.

For the treatment of constipation and accompanying gastric pain, such as caused by megacolon of Chagas’ disease, or even for congestive heart failure, Kallawayas used guayusa and sayre with an enema syringe to purge the patients. Tobacco is a particularly favored Andean remedy of long usage; it was widely used as a purgative and narcotic in pre-Columbian times.

Two species of tobacco, Nicotiana tabacum and rustica ( sayre ), were sources of narcotics in the Americas during the Incario (Elferink 1983; Schultes 1967, 1972). Nicotine was absorbed through the membranes of both the nose and anus by means of sniffing or the insertion of wild tobacco.

Guayusa and sayre were used by Kallawayas as early as A.D. 400, as indicated by a herbalist’s tomb found near Charazani that contained snuff trays and tubes for nasal inhalation, a gourd container for a powder, leaves from Ilex guayusa (Loes.), enema syringes, and a trephined and artificially deformed skull (Wassén 1972). Their purpose can only be guessed at: were they for medicine, stimulants, beverages, or ritual paraphernalia? The leaves are rich in caffeine, and guayusa was, and still is, used as a stimulant beverage in South America; for example, the people of Pasto, Colombia, still drink it. During the seventeenth century and after, the Jivaros of Rio Marañon drank it daily to stay awake, particularly when they feared attack by enemies (Patiño 1968). The Maynas of Peru and the Pinches of the Rio Pastaza region in Ecuador and Peru drank it for stomach disorders.

The ancient Kallawaya medicine man was equipped with enema syringes which were buried with him. One was made from a reed about 14 cm long, with a dried bulb of intestines tied to the tube with a cotton thread. Similar instruments appear in the Ollacha Valley of Bolivia, where Quechua Indians use them for enema syringes. The Jivaros of the Amazona region use similar syringes and prepare enemas from plants to purify the stomachs of male children. Andean diviners sometimes received enemas with narcotic fluids to enhance their spiritual powers (Tschudi 1918). The use of enemas during the Incario was important for warriors, who received douches before battle to become strong in battle (Guaman Poma 1944). Shortly after the Conquest, the medicinal qualities of sayre became known in Spain, where it was called a “holy weed” (Garcilaso de la Vega 1963).

Even today, Kallawayas claim that wild tobacco is an effective vermifuge and parasiticide. The Andean pharmacopeia featured potent parasiticides and vermifuges because of selective aspects or uses of certain plants able to kill predatory organisms. Kallawayas sometimes sniff tobacco leaves to induce sneezing for congestion and blockage of body parts. Air is understandably considered a vital fluid that must flow in and out of the nostrils; mucus must therefore be eliminated. Sniffing tobacco and guayusa not only cleanses these passageways by causing sneezing, tobacco also stimulates the cardiovascular system when nicotine enters the bloodstream. Thus some of the debilitating effects of chronic Chagas’ disease are meliorated.

Andeans conceptualize breath, samay, as a life force animating them and as a fluid element joining them with other vitalizing principles of the environment. Shortness of breath due to cardiac irregularities deeply puzzles Andeans, who feel that their lifeline with the natural world around them is cut off. The blockages of the esophagus, heart, and colon inherent in Chagas’ disease further turn the hydraulic processes inward in a damming effect of centripetal movement. The health of Andeans is believed by them to be a continual exchange of fluids with animals and plants, because they breathe the same air. For example, Kallawaya diviners communicate symbolically with the earth by blowing on their ritual offerings, which are then burned inside the earth shrines. Symbolically, breathing in and out is the means by which Kallawayas become united with their animals, land, and plants. Among a different ethnic group of ritualists, the people ofAusangate in southern Peru call their shamans samayuh runa, “ people possessing breath” (Jorge Flores, in Custred 1979). These shamans commune with the hill spirits by taking deep breaths. Breathing in is the way knowledge and power are received from the spirit, and breathing out in ritual context is the way they place themselves in the offering made to the earth.

Within the first millennium, humoral theories in Europe, Asia, and Africa held similar assumptions that the body’s physiology is a distillation process in which productive fluids are distilled from primary fluids of food, air, and liquids, and toxic fluids are eliminated in sweat, urine, and feces. These humoral theories, especially the Hippocratic-Galenic ones, assumed that the humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) were regulated according to principles of balance.

Kallawayas echoed European humoral theory in regard to fievre (fever), and they still treat acute cases of Chagas’ disease with cooling remedies. Andeans are primarily concerned with balancing the hot with the cold in dealing with fievre, rather than recognizing the fact that it could refer to parasitemia (parasites in the blood) and distinguishing acute phases of malaria, Chagas’ disease, and leishmaniasis. They refuse to bathe someone with a high fever in alcohol, which for them is classified as a hot remedy and should never be used to treat a hot disease ( fievre ). Because chagasic parasitemia is deadly for infants, health workers need to recommend a therapy that Andeans classify as cool, such as chamomile teas and baths (however, this varies with the region).

Читать дальше