His deepest needs have not been met in France. He has remained solitary. Loneliness is so common today in the metropolitan world of Western Europe and North America that the term has to cover a multitude of varieties. Old-age pensioners are lonely on park-seats. Old millionaires are said to be lonely as they look out at the world through their curtained windows. Some suffer loneliness in a crowd, others become lonely when there is not a soul in sight. We comfort ourselves by saying that it is also the privilege of great men to be lonely. But Picasso’s loneliness, if I am right, does not fit into any of these categories. He is lonely in the same way as a lunatic is lonely: because it seems to the lunatic that, since he never meets opposition, he can do anything. It is — by a paradox — the loneliness of self-sufficiency. This is not necessarily a loneliness that is suffered directly; more often it is a loneliness that provokes ceaseless activity and gives no rest. The worst thing in an asylum is that there is so little natural sleep. Perhaps it is foolish of me to use this image because it may confirm the philistine idea that Picasso is mad. He is not mad. Yet there is no other comparison which can illustrate so clearly what I mean. To explain why this should be so we must consider what Picasso has been exiled from: the Spain of his childhood and youth.

Picasso lived in Malaga until he was ten. Then the family moved to Corunna on the north Atlantic coast of Spain. When he was fourteen they moved again to Barcelona. Each of these cities is very different from the others — climatically, historically, and temperamentally. One of the difficulties of writing about Spain is that there are several Spains. Spain — in economic and social terms — has not yet achieved its unity. People speak of two Italies — north and south of Rome. One would have to speak of half a dozen Spains. This point is of crucial importance because it reminds us that Spain is historically behind the rest of Europe. Spain is separate.

Its geographical position and the fact that it is part of Christendom tend to deceive us. It would be truer to say that Spain represents a Christendom to which no other country has belonged since the Crusades. As for its geographical position, it might — if viewed with a fresh eye — be compared with Turkey’s. Certainly there is the Spanish contribution to European culture, but this also is deceptive. It is limited to literature and painting. It does not include the arts or sciences which are more directly dependent on comparable forms of social development; Spain has contributed little to European architecture, music, philosophy, medicine, physics, or engineering. Even, I would suggest, Spanish painting and literature have had less effect in Spain than outside Spain. They have belonged to those who could afford a vision of a way of life as it was lived in Europe, beyond the Pyrenees.

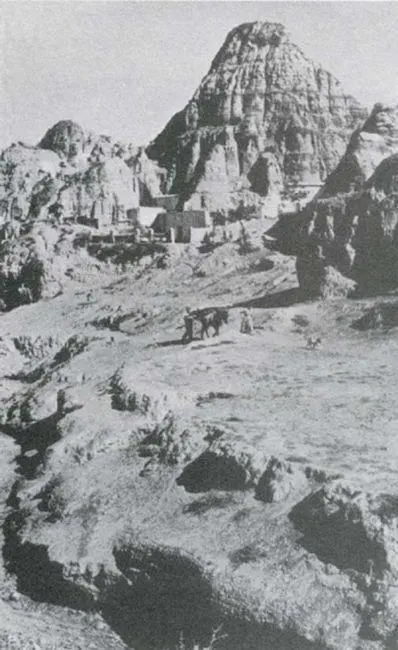

4 Spanish landscape

Spain is separate because Spain is still a feudal country. Seventy years ago, when Picasso was a boy, this feudalism was considerably less modified than today. Then, more than three quarters of the workers worked on the land. Their tools were primitive and the division of labour was only in a preliminary stage. In many areas production was only for household or village use. Compulsory labour-service was exacted, in various forms, by landlords from tenants. The landlords, by means of the ‘ cacique ’ system, had what amounted to judicial power of life and death over the peasants. These are all classic symptoms of feudalism. But pure classic feudalism is probably an abstraction. The Spanish variety at the end of the last century was complicated and impure.

5 Spanish peasants harvesting peppers

I am not equipped to unravel Spanish history here. But with a few rough generalizations and one or two examples I must attempt to suggest, however briefly, the period of Spanish development into which Picasso was born. Only then, I believe, have we a hope of understanding his spirit.

Spanish feudalism was complicated, distorted — in two opposed ways. On one hand there was a great deal in Spain which was pre-feudal; on the other hand there existed a very large administrative middle class — comprising nearly one fifth of the population.

The pre-feudal ‘relics’ were mostly to be found in isolated and inaccessible rural areas — but this term covers most of the land in Spain. In the Basque country and Navarre, for example, there was a system of land tenure in operation dating back to the tenth century and based on the clan system. On the vast, largely unworked estates in Andalusia, the labour system had more in common with Roman slavery than medieval feudalism. On the central plateau of Spain the sheep-farmers and cattle-breeders of Castile led a life which was essentially nomadic and tribal. But perhaps the most important ‘relic’ of all was to be found in the consciousness of the average Spanish peasant. Somehow he remembered a communal way of life — its exact form of organization varying greatly from province to province. This memory, combined with his bitter and unchanging poverty, made him despise private property and cling to an idea of freedom — which had nothing whatsoever to do with the liberté of the French Revolution, but which was the freedom and pride of the individual within a primitive, spontaneous, and small collective. He was the peasant who later, in the Civil War, wished to destroy all money.

The Spanish middle classes were born with the bureaucracy which was established in the sixteenth century to administer the Inquisition, the South American colonies, and the occupied territories in Italy and northern Europe. From the beginning, this bureaucracy was unproductive and vast in scale. A century after its formation the Venetian ambassador to Madrid wrote as follows:

Everyone who can, lives at the expense of the State. The number of all the government posts has been increased. In the Treasury alone there are more than 40,000 clerks, many of whom draw twice the pay that is assigned to them. Yet their accounts are wrapped in impenetrable and perhaps malicious obscurity and it is impossible to get any order or number out of them.

At the same period there were 24,000 tax collectors and 20,000 in the pay of the Inquisition. Such figures give some idea of the economic unreality of this class.

At first South American gold and Flemish industries paid for its maintenance. Later, as Spanish power declined, the burden was transferred to the Spanish economy itself, which was totally incapable of bearing it. Chronic impoverishment set in; there was no attempt to develop the economy, because this so-called middle class did not understand the link between capital and production: instead they sank back into provincial improvidence, proliferating only their ‘connexions’. By the middle of the last century every village postman owed his position — through a long chain of intermediaries — to a Minister in Madrid. When the government fell, the postman lost his job to a ‘supporter’ of the next government.

This is the general, typical history: there were exceptions. By Picasso’s time capitalist industrial enterprises had been started in the north, though still on a small scale. The middle-class young had joined the army and made junta plans to ‘modernize’ Spain. There was a liberal and European-orientated tradition in certain professions. In 1873 a Republic had been proclaimed, but it had lasted for only one year.

Читать дальше