Nonetheless, on August 23 that summer—the seventieth anniversary of the Nazi-Soviet Pact—the first European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism was solemnly marked in the Baltic states and Sweden. In subsequent years, the commemorations would spread. Wreathes would be laid, flags would be raised, and prayers would be offered across central and eastern Europe, from Poland to Crimea and from Estonia to Bulgaria. It was a small victory, perhaps, but a significant one. The Nazi-Soviet Pact had come out of the shadows. It was no longer forgotten, no longer taboo. It had become an essential part of the narrative.

APPENDIX

TEXT OF THE NAZI-SOVIET NONAGGRESSION PACT

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE GERMAN REICH AND THE GOVERNMENT of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, desirous of strengthening the cause of peace between Germany and the USSR, and proceeding from the fundamental provisions of the Neutrality Agreement concluded in April, 1926 between Germany and the USSR, have reached the following Agreement:

ARTICLE I. Both High Contracting Parties obligate themselves to desist from any act of violence, any aggressive action, and any attack on each other, either individually or jointly with other Powers.

ARTICLE II. Should one of the High Contracting Parties become the object of belligerent action by a third Power, the other High Contracting Party shall in no manner lend its support to this third Power.

ARTICLE III. The Governments of the two High Contracting Parties shall in the future maintain continual contact with one another for the purpose of consultation in order to exchange information on problems affecting their common interests.

ARTICLE IV. Neither of the two High Contracting Parties shall participate in any grouping of powers whatsoever that is directly or indirectly aimed at the other party.

ARTICLE V. Should disputes or conflicts arise between the High Contracting Parties over problems of one kind or another, both parties shall settle these disputes or conflicts exclusively through friendly exchange of opinion or, if necessary, through the establishment of arbitration commissions.

ARTICLE VI. The present Treaty is concluded for a period of ten years, with the proviso that, in so far as one of the High Contracting Parties does not advance it one year prior to the expiration of this period, the validity of this Treaty shall automatically be extended for another five years.

ARTICLE VII. The present treaty shall be ratified within the shortest possible time. The ratifications shall be exchanged in Berlin. The Agreement shall enter into force as soon as it is signed.

Done in duplicate, in the German and Russian languages.

MOSCOW, August 23, 1939.

For the Government of the German Reich:

v. Ribbentrop

Plenipotentiary of the Government of the USSR:

V. Molotov

Secret Additional Protocol.

ARTICLE I. In the event of a territorial and political rearrangement in the areas belonging to the Baltic States (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the northern boundary of Lithuania shall represent the boundary of the spheres of influence of Germany and the U.S.S.R. In this connection the interest of Lithuania in the Vilna area is recognized by each party.

ARTICLE II. In the event of a territorial and political rearrangement of the areas belonging to the Polish state, the spheres of influence of Germany and the U.S.S.R. shall be bounded approximately by the line of the rivers Narew, Vistula and San.

The question of whether the interests of both parties make desirable the maintenance of an independent Polish State and how such a state should be bounded can only be definitely determined in the course of further political developments.

In any event both Governments will resolve this question by means of a friendly agreement.

ARTICLE III. With regard to Southeastern Europe attention is called by the Soviet side to its interest in Bessarabia. The German side declares its complete political disinteredness in these areas.

ARTICLE IV. This protocol shall be treated by both parties as strictly secret.

Moscow, August 23, 1939.

For the Government of the German Reich:

v. Ribbentrop

Plenipotentiary of the Government of the USSR:

V. Molotov

From Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939–1941: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Office , ed. Raymond James Sontag and James Stuart Beddie (Washington, DC: Department of State, 1948), 76–78.

“Ours are better!” Guderian and Krivoshein enjoy the joint Nazi-Soviet parade at Brest, Poland: September 1939 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

Soviet and German troops exchange cigarettes and comradely greetings ( © IWM )

Molotov signs the Nazi-Soviet Pact under Stalin’s watchful eye: August 24, 1939 ( akg-images/Universal Images Group/Sovfoto )

“I know how much the German nation loves its Führer. I should therefore like to drink to his health.” Stalin and Heinrich Hoffmann share a celebratory toast in the Kremlin ( bpk/Bayerische Staatsarchiv/Archiv Heinrich Hoffmann )

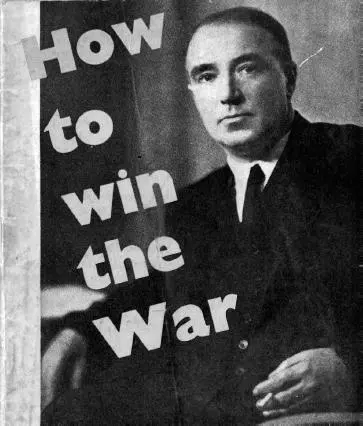

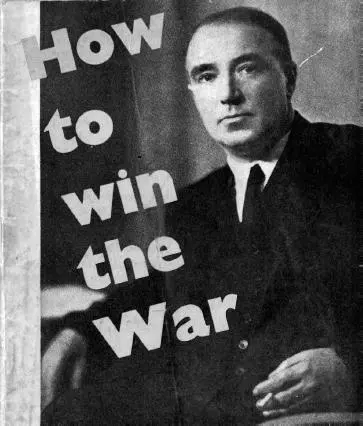

Harry Pollitt’s illstarred Communist Party pamphlet “How to Win the War,” which angered the Kremlin for advocating the defence of Poland ( author’s collection )

“The scum of the earth, I believe?” David Low’s iconic cartoon of September 1939, giving the Western view of the Pact’s dark cynicism ( Solo Syndication )

Hitler announces the German invasion of Poland to the Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House: September 1, 1939 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

Victorious German troops march through the ruins of a Polish village ( R. Schäfer, private collection )

Molotov announces the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September; in support of the USSR’s “brothers of the same blood” ( Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA )

A Red Army BT-7 tank trundles through the eastern Polish town of Raków, past the bewildered inhabitants ( akg-images/Universal Images Group/Sovfoto )

The German 6th Army parades before Hitler in former Polish capital, Warsaw: October 1939 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

The murderous reality of German rule. An execution in the Polish town of Sosnowiec: autumn 1939 ( akg-images/East News )

The Red Army parades through the Polish city of Lwów, past a portrait of Stalin: September 1939 ( Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA )

The murderous reality of Soviet rule. The corpses of a few of Stalin’s Polish victims, exhumed at Katyn: April 1943 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

Jews being deported by the Nazis from the city of Łódź in occupied Poland: March 1940 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

Replacing them, in theory, were ethnic Germans gathered from the areas ceded to Stalin by the Pact. Here Volksdeutsche from Bessarabia are loaded onto trains for the journey “Home to the Reich” ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

“This is how we annihilate the enemies of Soviet power.” A rare photograph of the mass deportation from Soviet-occupied Riga, the former Latvian capital: June 1941 ( Collection of the Occupation Museum of Latvia )

Condemned to “disappear… like a field mouse.” A deported Polish family from Stanisławów poses in front of their new “home” in Soviet Kazakhstan. They were amongst the lucky ones ( Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA )

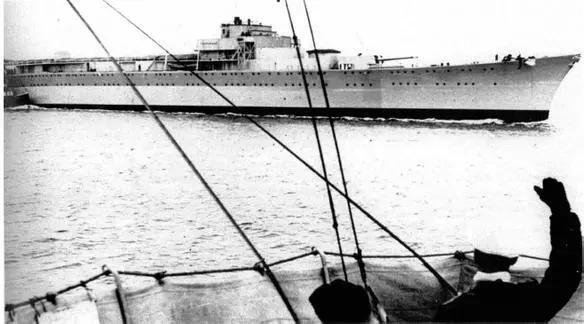

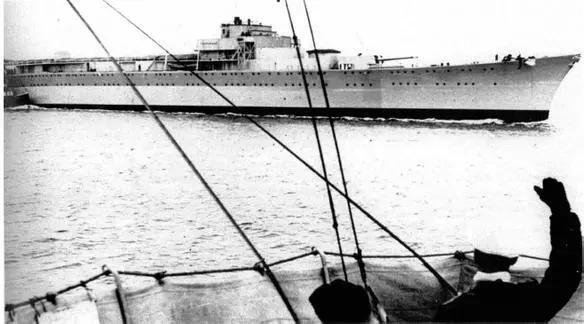

The unfinished German heavy cruiser “Lützow” — the “flag-ship” of the Nazi-Soviet Pact — being towed into Leningrad: May 1940 ( Russian Naval Archive/public domain )

The German-Soviet economic relationship; more important to Berlin “than a battle won.” Here an engineer checks the levels on a consignment of Soviet oil heading for Hitler’s Reich: Winter 1940 ( akg-images/picture-alliance )

Molotov arrives in Berlin in November 1940 to negotiate the next phase of the Nazi-Soviet Pact ( bpk/Bayerische Staatsarchiv/Archiv Heinrich Hoffmann )

“Let’s divide the whole world!” Hitler and Molotov discuss terms, with Gustav Hilger interpreting, but agreement eludes them ( bpk/Bayerische Staatsarchiv/Archiv Heinrich Hoffmann )

Anxious Moscow residents listen to Molotov’s radio announcement of the Nazi invasion. “Our cause is just,” he intoned, “Victory will be ours” ( akg-images/RIA Nowosti )

Goebbels reads Hitler’s announcement of the attack on the USSR to the German people. “I feel totally free,” he later wrote in his diary ( akg-images )

For many in Moscow’s newly-annexed territories — such as here near Chișinău in former Bessarabia — the invading Germans were greeted as liberators ( bpk/Hanns Hubmann )

“The only thing left of the 56th Rifle Division was its number.” Some of the countless thousands of Red Army soldiers who surrendered to the Germans in the opening days of Operation Barbarossa ( Klaas Meijer, private collection )

A destroyed T-34 tank, one of the few sources of optimism for Stalin in June 1941, and ironically one built in large part using German technology ( akg-images/interfoto )

Local civilians remove a statue of Stalin, only recently erected, in Białystok, Poland: July 1941 ( Bundesarchiv, Berlin )

Sikorski (left) and Maisky (right) sign the Polish-Soviet Agreement, in the presence of Eden and Churchill ( Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA )

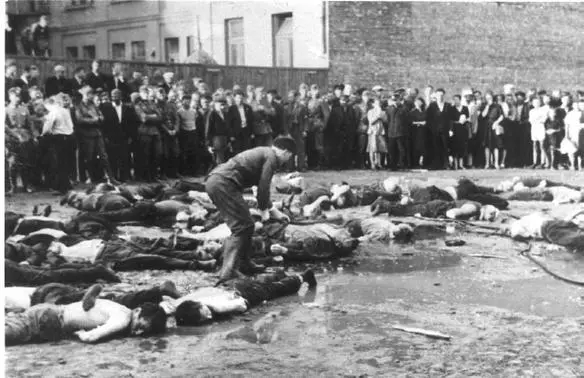

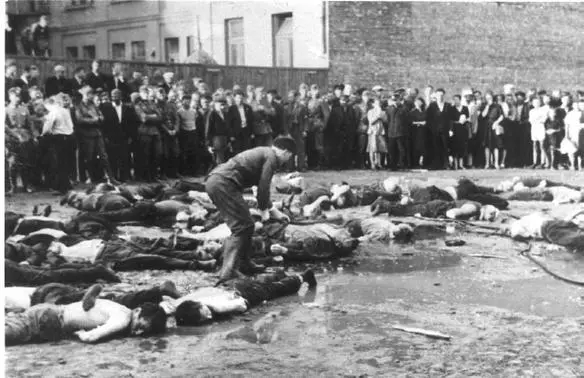

The Lietukis Garage Massacre. The Jews of Kaunas are beaten to death by the Nazis’ local collaborators: June 1941 ( DÖW )

Victims of the Soviet NKVD, strewn across the prison courtyard in Lwów, awaiting identification by their horrified relatives: June 1941 ( Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA )

The “Baltic Way” — a human chain that snaked its way through the Baltic republics of the USSR on the 50th anniversary of the Nazi-Soviet Pact — in protest at Stalin’s annexation of the three countries: August 1989 ( Museum of Occupations, Tallinn, Estonia )

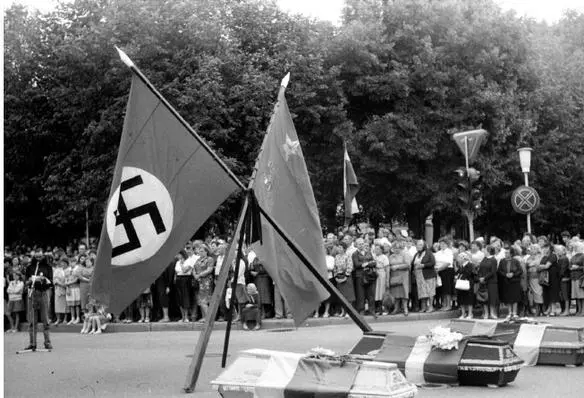

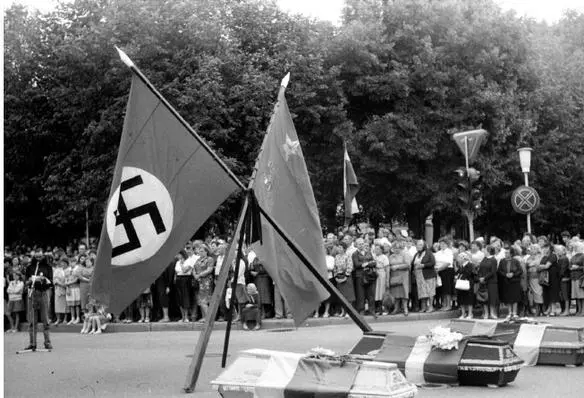

This demonstration, at Šiauliai in Lithuania, made the connection brutally clear — showing the three Baltic republics as coffins, with the Nazi and Soviet flags joined over them: August 1989 ( Rimantas Lazdynas )

Читать дальше