John Fiske - The American Revolution

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Fiske - The American Revolution» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: История, foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The American Revolution

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The American Revolution: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The American Revolution»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The American Revolution — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The American Revolution», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

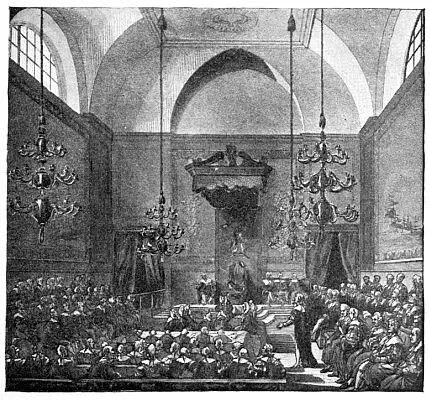

HOUSE OF LORDS

We may perhaps wonder that a British Parliament should have been prevailed on to pass such audacious acts as these, and by large majorities. But we must remember that in those days the English system of representation was so imperfect, and had come to be so overgrown with abuses, that an act of Parliament was by no means sure to represent the average judgment of the people. The House of Commons was so far under the corrupt influence of the aristocracy, and was so inadequately controlled by popular opinion, that at almost any time it was possible for an eloquent, determined, and unscrupulous minister to carry measures through it such as could never have been carried through any of the reformed Parliaments since 1832. It is not easy, perhaps, to say with confidence what the popular feeling in England was in 1767 with reference to the policy of Charles Townshend. The rural population was much more ignorant than it is to-day, and its political opinions were strongly influenced by the country squires, – a worthy set of men, but not generally distinguished for the flexibility of their minds or the breadth of their views. But as a sample of the most intelligent popular feeling in England at that time, it will probably not be unfair to cite that of the city of London, which was usually found arrayed on the side of free government. No wiser advice was heard in Parliament, on the subject of the New York dispute, than was given by Alderman Beckford, father of the illustrious author of Vathek, when he said, “Do like the best of physicians, and heal the disease by doing nothing.” On many other important occasions in the course of this unfortunate quarrel, the city of London gave expression to opinions which the king and Parliament would have done well to heed. But even if the House of Commons had reflected popular feeling in 1767 as clearly as it has done since 1832, it is by no means sure that it would have known how to deal successfully with the American question. The problem was really a new one in political history; and there was no adequate precedent to guide the statesmen in dealing with the peculiar combination of considerations it involved. As far as concerned the relations of Englishmen in England to the Crown and to Parliament, the British Constitution had at last reached a point where it worked quite smoothly. All contingencies likely to arise seemed to have been provided for. But when it came to the relations of Englishmen in America to the Crown and to Parliament, the case was very different. The case had its peculiar conditions, which the British Constitution in skilful hands would no doubt have proved elastic enough to satisfy; but just at this time the British Constitution happened to be in very unskilful hands, and wholly failed to meet the exigencies of the occasion.

The chief difficulty lay in the fact that while on the one hand the American principle of no taxation without representation was unquestionably sound and just, on the other hand the exemption of any part of the British Empire from the jurisdiction of Parliament seemed equivalent to destroying the political unity of the empire. This could not but seem to any English statesman a most lamentable result, and no English statesman felt this more strongly than Lord Chatham.

There were only two possible ways in which the difference could be accommodated. Either the American colonies must elect representatives to the Parliament at Westminster; or else the right of levying taxes must be left where it already resided, in their own legislative bodies. The first alternative was seriously considered by eminent political thinkers, both in England and America. In England it was favourably regarded by Adam Smith, and in America by Benjamin Franklin and James Otis. In 1774, some of the loyalists in the first Continental Congress recommended such a scheme.

In 1778, after the overthrow of Burgoyne, the king himself began to think favourably of such a way out of the quarrel. But this alternative was doubtless from the first quite visionary and unpractical. The difficulties in the way of securing anything like equality of representation would probably have been insuperable; and the difficulty in dividing jurisdiction fairly between the local colonial legislature and the American contingent in the Parliament at Westminster would far have exceeded any of the difficulties that have arisen in the attempt to adjust the relations of the several States to the general government in our Federal Union. Mere distance, too, which even to-day would go far toward rendering such a scheme impracticable, would have been a still more fatal obstacle in the days of Chatham and Townshend. If, even with the vast enlargement of the political horizon which our hundred years’ experience of federalism has effected, the difficulty of such a union still seems so great, we may be sure it would have proved quite insuperable then. The only practicable solution would have been the frank and cordial admission, by the British government, of the essential soundness of the American position, that, in accordance with the entire spirit of the English Constitution, the right of levying taxes in America resided only in the colonial legislatures, in which alone could American freemen be adequately represented. Nor was there really any reason to fear that such a step would imperil the unity of the empire. How mistaken this fear was, on the part of English statesmen, is best shown by the fact that, in her liberal and enlightened dealings with her colonies at the present day, England has consistently adopted the very course of action which alone would have conciliated such men as Samuel Adams in the days of the Stamp Act. By pursuing such a policy, the British government has to-day a genuine hold upon the affections of its pioneers in Australia and New Zealand and Africa. If such a statesman as Gladstone could have dealt freely with the American question during the twelve years following the Peace of Paris, the history of that time need not have been the pitiable story of a blind and obstinate effort to enforce submission to an ill-considered and arbitrary policy on the part of the king and his ministers. The feeling by which the king’s party was guided, in the treatment of the American question, was very much the same as the feeling which lately inspired the Tory criticisms upon Gladstone’s policy in South Africa.

Lord Beaconsfield, a man in some respects not unlike Charles Townshend, bequeathed to his successor a miserable quarrel with the Dutch farmers of the Transvaal; and Mr. Gladstone, after examining the case on its merits, had the moral courage to acknowledge that England was wrong, and to concede the demands of the Boers, even after serious military defeat at their hands. Perhaps no other public act of England in the nineteenth century has done her greater honour than this. But said the Jingoes, All the world will now laugh at Englishmen, and call them cowards. In order to vindicate the military prestige of England, the true policy would be, forsooth, to prolong the war until the Boers had been once thoroughly defeated, and then acknowledge the soundness of their position. Just as if the whole world did not know, as well as it can possibly know anything, that whatever qualities the English nation may lack, it certainly does not lack courage, or the ability to win victories in a good cause! All honour to the Christian statesman who dares to leave England’s military prestige to be vindicated by the glorious records of a thousand years, and even in the hour of well-merited defeat sets a higher value on political justice than on a reputation for dealing hard blows! Such incidents as this are big with hope for the future. They show us what sort of political morality our children’s children may expect to see, when mankind shall have come somewhat nearer toward being truly civilized.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The American Revolution»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The American Revolution» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The American Revolution» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.