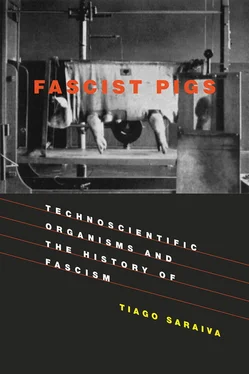

For such purposes Canguilhem’s pamphlet holds a few more precious insights. First, it deals simultaneously with the agricultural policies of the fascist regimes in Italy and Germany, emphasizing the continuities between those two regimes and the ideology of the French Greenshirts. Second, and perhaps more important, it includes in its discussion of fascism the new varieties of wheat that increased yields at the expense of milling properties. Canguilhem establishes a direct relation between large farmers’ interests in increasing productivity through new strains of wheat and the appearance of a generic fascist discourse promising the nation’s attachment to the land while ignoring the diverse concrete situations that constituted the peasant world. This book builds on Canguilhem’s attention to specific technoscientific organisms to explore the historical dynamics of fascism. In part I, wheat, potatoes, and pigs will guide us through the early stages of the institutionalization of fascism in Italy, Portugal, and Germany. In part II, sheep, cotton, coffee, and rubber will take us into the violent colonial expansion of the three regimes in Africa and in eastern Europe.

Hans-Jörg Rheinberger has recently revisited Canguilhem’s work and has disclosed far-reaching consequences of Canguilhem’s apparently limited considerations on the object of history of science. [10] Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, An Epistemology of the Concrete: Twentieth-Century Histories of Life (Duke University Press, 2010).

Canguilhem’s recognition that “there can be no history of truth that is exclusively a history of truth, nor a history of science that is exclusively a history of science” demands, according to Rheinberger, a focus on the social and technological concerns from which the sciences arise. [11] Ibid., p. 47.

Canguilhem’s discussion of Claude Bernard’s experimental medicine is particularly illuminating in this respect in that it invokes “the demiurgic dream dreamed by all industrial societies in the mid-nineteenth century, the period when the sciences, thanks to the applications of them, became a social force.” [12] Ibid., pp. 47–48.

The claim thus goes beyond accepting that one must know the social and economic contexts to understand the history of science. One should also recognize the creative power of the experimental sciences and their ability to blur the distinction between knowledge and creation: new things are brought into existence changing those contexts; they constitute a “social force” in themselves. That was what Canguilhem hinted at when connecting the production of new strains of wheat with the rise of fascism in the French countryside. But only in that early pamphlet did he specify the concrete ways in which scientific and technological things changed major political contexts.

This book recovers that early engagement by Canguilhem and aims at understanding how new strains of wheat and potatoes, new pig breeds, and artificially inseminated sheep contributed in significant ways to materialize fascist ideology. These organisms are taken as “technoscientific thick things” that, in contrast to the thin scientific objects isolated from society of traditional accounts, bond science, technology, and politics together in a continuum. [13] In the conclusion I discuss the implications of the use of the notion of “things” in place of “objects” in history of science writing in more detail. For other discussions, see Ken Alder, “Introduction to focus section on thick things,” Isis 98, no. 1 (2007): 80–83; Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik,” in Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy , ed. B. Latour and P. Weibel (MIT Press, 2005); Lorraine Daston, ed., Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science (Zone, 2004); Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube (Stanford University Press, 1997).

This is not a study about what happened to scientists under fascism, but one that, by following the historical trajectories of technoscientific things, reveals how new forms of life intervened in the formation and the expansion of fascist regimes. It doesn’t take fascism as the historical context in which certain scientific undertakings have place, preferring instead to focus on the ways technoscientific organisms became constitutive of fascism. [14] The approach of considering technology and science as constitutive of the political realm owes much to Bruno Latour. Among many possible references, see Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik”; Latour, Politiques de la nature: comment faire entrer les sciences en démocratie (La Découverte, 1999). The notion of co-production of science and politics emphasizes the same historical dynamics. See Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (Princeton University Press, 1985); Sheila Jasanoff, ed., States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order (Routledge, 2004). For an exemplary treatment of the relation between science, technology, and politics, see Ken Alder, Engineering the Revolution: Arms and Enlightenment in France, 1763–1815 (Princeton University Press, 1997); Gabrielle Hecht, The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity after World War II (MIT Press, 1998); Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity (University of California Press, 2002). Soraya de Chadarevian, Designs for Life: Molecular Biology after World War II (Cambridge University Press, 2002); David Edgerton, Warfare State: Britain, 1920–1970 (Cambridge University Press, 2005); John Krige, American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (MIT Press, 2006).

Fascism as Alternative Modernity

In spite of the long and respectable pedigree of historical studies that have explored the relation between science and Nazism, to my knowledge there is no single work in history of science dealing with science and fascism more broadly. [15] For a first collective attempt at writing such history, see Tiago Saraiva and M. Norton Wise, “Autarky/autarchy: Genetics, food production, and the building of fascism,” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 40, no. 4 (2010): 419–428.

When the word ‘fascism’ shows up in narratives produced by historians of science, it refers to singular fascist regimes (Hitler’s, Mussolini’s, or Franco’s), always taken separately. [16]This is surprising when we consider the large literature in European history that discusses fascism as a widespread phenomenon and as a historical concept in its own right. [17]As “the major political doctrine of world-historical significance created during the twentieth century,” fascism is undoubtedly an essential part of European modern history. [18]If every developed nation in the world with some degree of political democracy had some kind of fascist movement in the interwar years, the vast majority of European countries went a step further in their relation with fascism. Adding to the two canonical cases of Italy and Germany, where fascist movements seized power, we can’t avoid fascism when dealing with the political regimes of Dolfüss in Austria, Horthy in Hungary, Antonescu in Romania, Metaxas in Greece, Pétain in France, Franco in Spain, and Salazar in Portugal. There is, of course, no consensus in the historiography on the proper typology of all these different regimes. But independent of labeling them as fascist or not, historians agree that they all had significant fascist dimensions, forming what Roger Griffin describes as “para-fascism” and Michael Mann calls “hyphenated fascist regimes”: Metaxas’ “monarcho-fascism,” Dolfüss’ “clerico-fascism,” and so on. [19]Not only does the inclusion of the Portuguese case in this book present a national context normally absent from the history of science and the history of technology; in addition, it has the advantage of placing the argument in this wider context of Europe’s experience with fascism. [20]The Portuguese fascist regime is in many ways exemplary of dynamics common to those hyphenated or para-fascist cases. Also, the longevity of the Portuguese dictatorship (1926–1974) and the imperial dimensions of Salazar’s New State contribute decisively to make it a historical object to consider side by side with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Historians of science and technology commonly argue for more attention to their disciplines from those interested in general history, but historians of science and technology have been largely absent from the significant debates concerning the history of fascism. This book seeks to overcome that limitation by considering the connected experiences with fascism of three different countries.

Читать дальше