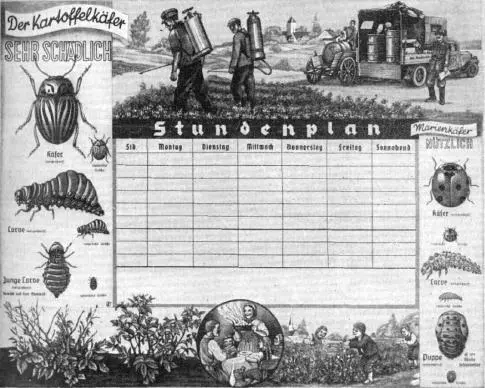

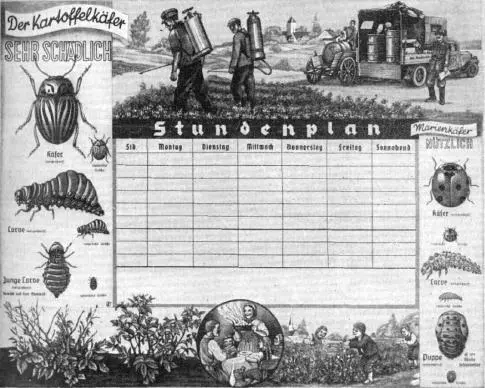

Figure 3.8 A 1937 elementary school chart with illustrations showing the differences between the harmful (schädlich) Colorado potato beetle from the useful (nützlich) ladybug.

( Nachricthenblatt für den Deutschen Pflanzenschutzdienst 17, no. 7, 1937: 53)

By 1941, the BRA claimed to have its campaign against the Colorado Beetle underway in 82 villages and cities in western Germany, the areas more afflicted by the beetle. At least 204,000 hectares had been cleared by the brigades of the Defense Office, which included 88 advisors, 91 office workers, 279 technicians, 97 truck-drivers, 43 co-drivers, 24 mechanics and foremen, and 20 auxiliary men. In the same year, 4,536 training courses were reportedly attended by about 700,000 Germans, 600,000 Alsatians, and 350,000 people from Lorraine. [78]Even if we discount the exaggerated numbers, there is little doubt about the capacity of the Nazis’ plant-protection campaigns to reach large shares of the population. [79]The training courses, the images on children’s calendars, and the demonstration kits all contributed to making the Colorado Beetle into an enemy menacing the survival of the national community. Every finding and subsequent elimination of a beetle was transformed into a significant contribution to the food battle keeping the German race alive. Through such operations everyone was able to feel that he or she was contributing to a major transcendent cause even when performing the apparently humble task of searching a field for bugs. To be sure, many other pest-control campaigns in Germany had invoked the presence of the enemy in national soil and the need to exterminate it by means of chemical warfare. But the high rhetoric of earlier campaigns did not match the mobilization of local populations at such a grand scale as during the Nazi years, involving hundreds of thousands of villagers, women and children included, in a kind of participatory science for the defense of the Fatherland.

Neither wart nor the Colorado Beetle could compete with the significance of late blight, the pest that allegedly had caused Germany’s defeat in World War I. It is thus not surprising that Karl Otto Müller, the scientist responsible for releasing the first breeds of potatoes resistant to late blight, became the most celebrated figure of the Biologische Reichsanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft. Müller was the head of the Genetics and Breeding Section of the Botany Department of the BRA from 1927 to 1945. [80]After his studies at the University of Berlin with such luminaries of genetics as Carl Correns and Eugen Fischer, he went to work for the BRA in 1922 as a research assistant to Josef Broili, who was then in charge of the BRA’s plant-breeding efforts. [81]

In 1911 Broili had obtained from the US Department of Agriculture a number of wild South American Solanum plants which he could not identify precisely and which were subsequently subjected to intense inbreeding. This work established the hybrid character of one of the species and led Broili to label its progeny as F-varieties (the F standing for ‘fraglich’, which means “doubtful”). [82]From the beginning he was interested in exploring the potential of such material to introduce resistance to late blight into commercial varieties. [83]Nevertheless, according to Müller’s own account, World War I and the ensuing difficulties in getting technical assistance hindered Broili’s breeding plans. It was only after Müller’s arrival in 1922 at the BRA that a systematic comparison was made between the F-varieties and commercial ones. That comparison would establish the immunity of the F-varieties to late blight attacks.

The most distinguishing feature of the breeding work at the BRA was the importance given to the procedure for exposing plants and tubers to a pathological agent. To develop standardized laboratory methods of infection was a mandatory first step toward the breeding of resistant strains. [84]These methods sought to guarantee not only that selections would be made properly and that plants would be exposed to pathogens, but also that the entire procedure would be streamlined in order to screen a large number of specimens.

The first step undertaken by Müller to explore the resistance of the F-varieties was to infect young shoots of potatoes with fresh-hatched zoospores of the fungus responsible for late blight ( Phytophthora infestans ) under optimal conditions for the development of the latter. Next he increased efficiency by using seedlings instead of shoots, placing them in pad-stitched boxes. After the seedlings developed their first three or four leaves, he applied a few droplets of a solution containing the Phytophthora zoospores. Susceptible seedlings would die, while immune ones would survive. In a small laboratory with modest resources, Müller was thus able to screen thousands of seedlings in a relatively short period of time. [85]

From 1925 on, the method was intensively used by Müller in his crossings of F-varieties with commercial cultivars. It enabled him to prove that resistance to late blight was inherited independently of crucial economic properties such as yielding and time to maturity. [86]He named the hybrids thus obtained the W-varieties, which he soon was publicizing among German commercial breeders and among fellow public breeders abroad. [87]The W-varieties promised to end one of the chief afflictions of European farmers, responsible not only for the mid-nineteenth-century Irish famine but also in large part for the disastrous food shortages in Germany during World War I.

The memory of the “turnip winter” of 1917 was repeatedly invoked to assert the relevance of the BRA phytopathology work to the Nazi Battle of Production. [88]By the 1930s the losses due to late blight were estimated at a third to a half of the total potato crop. [89]The combination by Müller of standardized inoculation methods with the employment of wild varieties from South America holding the desired resistance genes confirmed the capacity of modern plant breeding to overcome the major challenges faced by European agriculture. Allegedly, it was just a question of time for commercial breeders to start releasing resistant varieties by crossing Müller’s W-varieties with high-yielding European cultivars. In 1934 the Sandnudel made its appearance in the RNS Reichssortenlist as the first commercial variety resistant to Phytophthora infestans , the first enemy of the potato plant. [90]Thanks to the technoscientific organisms coming out of the BRA, Darré’s promises that the national soil would feed the national community didn’t seem crazy reveries. Germans could remain “children of the potato.”

But scientific triumphs are never easy. By 1932 the von Kameke seed company of Streckenthin (Brandenburg) had reported that the W-varieties it was working with had undergone a severe attack of late blight. [91]According to R. Steven Turner, this event marked the beginning of the fall of the heroic age of late blight resistance breeding. Rudolf Schick of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institut für Züchtungsforschung, was quick in criticizing Müller for not having anticipated such possibility. Schick was referring in concrete to the existence of different biotypes of the fungus, which explained the vulnerability of the W-varieties. Contrary to initial hopes, Phytophthora infestans was able to develop new biotypes, a problem plant breeders were very well aware of from their previous experience with the black stem rust of cereals. By 1936, scientists at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institut für Züchtungsforschung had identified eight different biotypes of P. infestans . [92]

Читать дальше