Altner’s foot wound proved to be a blessing in disguise. Instead of being marched off to the east, he was taken for treatment in a hospital in Brandenburg. Many others were not so fortunate.

Chapter Eleven

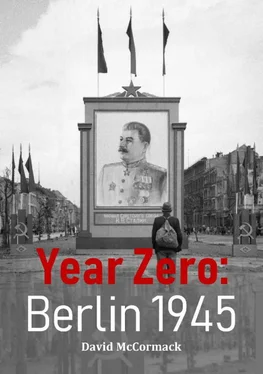

After Hitler

In Berlin, the end of hostilities brought about a sense of relief, mixed with feelings of anxiety about what was to come. The master race were now the conquered, subject to the whims of a people whom Goebbels had characterised as Asiatic barbarians. Indeed, there were acts of barbarism, in which mainly second echelon troops indulged in an orgy of looting and rape. The women of Berlin soon learned to make themselves scarce at night, only emerging in the morning as Soviet troops slept following the drunken excesses of the night before. The number of rape victims in Berlin remains difficult to determine accurately, as some women and young girls were subjected to multiple assaults. For the depersonalised and desexualised young frontovki, rape was very much a group activity. Estimates suggest that there were as many as 100,000–130,000 victims of this appalling crime. If the terrible experiences of the female population of East Prussia are taken as an indication, this figure is certainly not too high, rather it may be something of a conservative estimate.

For all the terrible events that accompanied the fall of Berlin, the occupation policies of the newly established Soviet military administration largely contradicted Goebbels’ terrifying predictions of what would happen to a conquered German population. In what little remained of the Nazi state, Hitler’s theories of racial hatred were perpetuated by his appointed successor and his government in Flensburg. On 2 May, Schwerin von Krosigk (Foreign Minister in Doenitz government) took to the airwaves to highlight the suffering of German civilians at the hands of the rapacious Red Army:

The world can only find peace if the Bolshevik tide does not flood Europe. In a heroic struggle without parallel, for four years Germany fought to its last reserves of strength as Europe’s bulwark, and that of the world, against the Red menace. In the east, an iron curtain is advancing, and behind it, hidden from the eyes of the world, the work of exterminating those who have fallen into Bolshevik hands goes on.

Krosigk’s speech was an outrageous distortion of history which made no mention of the Nazi terror apparatus. Whilst the Soviet administration was unquestionably harsh, there were no ghettoes, no gas chambers. Germans living in the Soviet zone of occupation were not to be killed en masse, but converted to the cause. Whilst the German armed forces formally surrendered to the Allies on 8 May at Karlshorst (Berlin), the Doenitz administration continued to enact a sham form of government until it was wound up by the British authorities on 23 May.

Meanwhile, in Berlin the issues facing the conquerors were very real. Before the political indoctrination of the defeated population could begin, the shattered city had to begin functioning again. The infrastructure of the once great city of Berlin had collapsed. Streets were choked with debris, trains and trams no longer functioned, power plants, pumping stations and gas works were largely destroyed. However, the most pressing problem was food. Stalin made a political decision to feed the German population.

With Nazi Germany defeated, the differences between the incompatible political systems which made up the Grand Alliance became more marked. During this early stage of the Cold War, Stalin prioritised the needs of Germans above his own citizens. In his memoirs, Zhukov recalled the implementation of Stalin’s policy:

The population of Berlin had to be saved from starvation. The supply of foodstuffs, which had been stopped before the Soviet troops entered Berlin had to be organised. It turned out that large groups of the population had received no food for several weeks. The Soviet troops stationed in Berlin began to extinguish the fires, organise the removal and burial of corpses, and de-mine whole areas. The Soviet command, however, could not solve all these problems without involving masses of the local population in active work.

With few men left, the workforce available to the Soviet administration consisted mainly of women. Soon, the ‘Rubble Women’ became a feature around Berlin’s shattered streets. Work meant food, and in the ruined capital there was certainly no shortage of clearance work.

It was left to General Berzarin (Military Commander of Berlin) to put Stalin’s plans into practice. He soon became a well liked and respected figure in Berlin as he mingled with German civilians queuing at field kitchens. His tenure was however short-lived, as after only fifty-five days in office, he was tragically killed in an accident. Rumours spread that he had been murdered by the NKVD, or even by Nazi Werewolf fanatics (Bezarin was killed in a tragic road traffic accident). During his short time in office, this energetic officer achieved minor miracles by establishing order, reintroducing essential services and feeding the population. The long process of winning over the German population had begun.

The catastrophic defeat of Hitler’s Germany was greeted with mixed feelings by ordinary Berliners. By July 1945, the city was full of American, British, French and Soviet troops. The famed wit of Berliners largely focused on lampooning the occupiers. A popular joke of the time concerned the old Berliner who was asked which nationality he liked most. After ruminating for a while, the man replied – ‘The Siamese’. When it was pointed out to him that there were no Siamese occupying forces in Berlin, he put his head to one side and said – ‘Ah, so? Why come to think of it, there aren’t’. Whilst you won’t need treatment for cracked ribs after laughing too much at this joke, it does nonetheless serve to demonstrate how humour was used by many as a coping strategy.

Richard Brett-Smith, a young officer serving with the 11 thHussars in Berlin (July 1945 – March 1946) was a keen observer and chronicler of Berlin life. His observations go some way towards explaining the attitude of the average Berlin citizen towards defeat and occupation:

In Berlin I found most people more resilient than in other German cities, and certainly as quick-witted, sharp, and cheerful as the London Cockney. Perhaps Berlin is the one place in Germany where a sense of humour near to that of the English is often found. It was amazing that in 1945 a people in such straits could laugh at all, and miraculous that they should laugh at and make jokes about their own troubles and afflictions, such as the Russians, the Black Market, the Red Caps (British Military Police) or ‘Snowballs’ (American Military Police) and food rationing… To me, it was the Berliners’ sense of humour and individuality which most distinguished him from other Prussians. So often it depends upon a lampooning of authority with that wry cynicism about one’s own plight

The wry wit which Brett-Smith observed was both an acknowledgement by Berliners of their own much reduced circumstances and their resilience in the face of adversity. They had survived the bombing and the coming of the Soviet armies. Through their humour, toughness and adaptability, they would survive the occupation too.

Hitler once said, ‘Give me ten years and you won’t recognise this country’. In the event, Hitler’s dictatorship lasted twelve years, by which time the country was indeed unrecognisable. The great cities of Germany lay in ruins. Factories were either destroyed or lay idle due to acute shortages of fuel and raw materials. Public utilities had ceased to function. Life revolved around securing the basic necessities of food, shelter and warmth. People lived a troglodyte existence in the cellars of bombed and burnt-out buildings. As they scurried around the ruins like ants, thick dust clung to their clothes and faces, giving them a ghostly appearance. The celebrated war correspondent Alan Moorhead described life in these shattered German cities as ‘sordid, aimless, leading nowhere’.

Читать дальше