Meanwhile, the man whom Hitler referred to as ‘My loyal Heinrich’ was making plans of his own. His special-plenipotentiary, Brigadier-General Walter Schellenberg, along with his masseur and confidant Felix Kersten had arranged meetings that day with Count Folke Bernadotte, the vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross, and Norbert Masur, who at short notice had replaced Gilel Storch as the visiting representative of the World Jewish Congress. Both Bernadotte and Masur had assumed that Himmler had wanted to discuss the possible release of concentration camp prisoners. This was certainly part of Himmler’s thinking at the time, though his main concern was in opening up channels of communication with General Eisenhower.

When Count Bernadotte arrived in Berlin, Schellenberg informed him that Himmler was unable to see him immediately. Following an air-raid alert, he set off for the comparative safety of the Swedish Legation air raid shelter, on the way noting that ‘Berlin had become a silent city’. After spending several hours in the shelter, Bernadotte was driven to Hohenlychen Sanatorium where medical superintendent Dr Karl Gebhardt was waiting to welcome him. Several more hours passed, largely as a consequence of Himmler’s vacillation. Evidently, he could still not fully commit to what amounted to treason against his beloved Fuhrer.

Meanwhile, Masur had also arrived in Berlin, accompanied on the flight from Stockholm by Kersten. Masur and Kersten were the only passengers and during the flight the representative of the World Jewish Congress reflected on his mission:

For me as a Jew, it was a deeply moving thought, that, in a few hours, I would be face to face with the man who was primarily responsible for the destruction of several million Jewish people. But my agitation was dampened by the thought that I finally would have the important opportunity to be of help to many of my tormented fellow Jews. I had been in the midst of other missions before, but always from the safety of Stockholm. This time it was action at the front lines.

Masur was indeed stepping into the lion’s den. However, his composure was only to be admired. Thankfully, the journey to Berlin was without incident. Later, Masur documented his experiences in detail. As such, we have an accurate record of the run-up to the meeting, and later, the meeting itself. Masur’s recollections of his arrival in Berlin effectively chronicle the slow death of a once great city, and as such they are worth quoting in extensio:

The North-German plain passed peacefully in front of our eyes. The fields seemed to be tended carefully. Only once did I discern a bomb crater, the first sign of war, otherwise there were no traces. No soldiers or motorised columns were visible, only an occasional farmer. However, when we approached Berlin, the signs of war became more evident, bombed out houses, factories without roofs…

At the Templehof airport, my companion showed his passport, however I kept mine in my pocket. I did not have a visa, because only Himmler and his closest associates knew about our visit, it was held in complete secrecy from all the other Nazi bosses. Because of this, I could not apply for a visa at the German embassy in Stockholm. The Gestapo simply ordered that a man in the company of Dr Kersten should be admitted without passport control.

At the airport, the limousine of the Swedish embassy was waiting to take us into the city. However, we could not use this car, and had to wait for a Gestapo car, as we were to proceed to an estate approximately 70 km north of Berlin. Unfortunately, we had to wait almost 2 hours. In the meantime, I had the opportunity to get a first impression of the atmosphere in Berlin. I had a conversation with some of the workers at the airport, and was able to discern that they were war-weary and without hope. Every night, air-raids lasting 5 to 7 hours, therefore they had to spend a long time in uncomfortable air-raid shelters without sleep, that is too much for even the strongest person. The air-raids occur with the punctuality of a time table. Every evening, shortly after dark, the Russians begin the attacks, followed by the Americans, and the British would finish the raids.

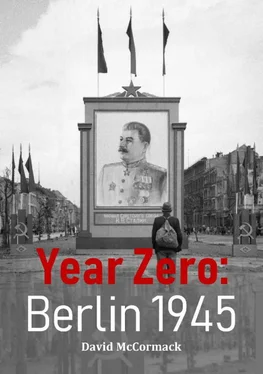

Because of this it was important for us to get out of town before the beginning of the air-raids. Around 10 pm, the car arrived, and the excuse was that the telephone connection with Stockholm was interrupted, and they did not know for sure if we were coming. The car left immediately, it was dark, and the moon was shining. The ruins of the houses were like ghosts. The driver sped through the city, which looked as if it were dead… We passed rows of destroyed houses, and drove through the narrow openings of tank-traps. Several times we had to take a detour to avoid streets that had recently been closed because of the bombings.

Finally, after an hour, we were out of Berlin and on the highway. It only took a few minutes before a military patrol stopped us and asked the driver to turn off the headlights, as there was an air alert. The nightly show over Berlin had started… The anti-aircraft searchlights began to play in the sky, and we stopped and got out of the car to watch the sinister, but fascinating show. From all sides we heard the whirring of propellers, which our driver, with his trained ears, identified as Russian. We saw how illumination flares spread out like a carpet, slowly descending to the ground, lighting up the entire area, how planes would be trapped in the spotlights, but we did not hear any flak. At my question as to why there was no shooting, I got the significant answer that all the flak ammunition had been sent to the front.

We continued, past suddenly appearing military vehicles, past mounds of destruction in the town of Oranienburg, which had suffered an air raid recently. For me, the name Oranienburg was ominous, as here many of my closest relatives became acquainted with the terror of the concentration camps, before I was able to rescue them to emigrate into Sweden.

Finally, close to midnight, we arrived at our destination, an estate belonging to Dr Kersten. Here we were supposed to await the visit by Himmler. That night I was not able to sleep. Not because of the constant noise from the planes, but the tension at the thought of my meeting with Himmler… Even though I knew that Himmler’s reason for negotiating was the catastrophic war situation in Germany, I believed that many important results might come out of these negotiations.

Masur’s tension was further exacerbated the following morning when Schellenberg informed him that Himmler would be delayed as he was attending Hitler’s birthday celebrations at the Reich Chancellery. Masur later recorded his thoughts, stating with incongruity that, ‘Hitler should only have known that Himmler, after the birthday party, would be negotiating with a Jew!’. Whilst he waited for Himmler, Masur had a long conversation with Schellenberg, whom he found to be sincere. Later, he spoke with workers on the estate, and after gaining their trust, was able to learn more about the mood of the German people.

In Berlin, a few posters and banners had gone up by way of celebrating the Fuhrer’s birthday. In Moabit, a large banner was strung across a street near to the prison. The citizens of Berlin were well noted for their sense of humour, as such the message on the banner, which read, ‘We all pull on the same rope. Up the Fuhrer’ was interpreted with a wry smile by many. As was the norm on Hitler’s birthday, the weather was fine. There would however be no parades, no visible confirmation of a German culture triumphant. This last gathering of the Nazi elite was more of a wake than a celebration.

On the morning of his birthday, Hitler arose at 11.00hrs. Following brief birthday felicitations from the bunker entourage, he asked about the current military situation. The latest news from the crumbling battle fronts was hardly encouraging. It was clear that American and Soviet spearheads would soon link-up, cutting Germany in two. Hitler was urged to leave Berlin for the comparative safety of the Bavarian mountains. He rejected any suggestion that he should abandon Berlin by saying, ‘How am I to call on the troops to undertake the battle for Berlin, if at the same moment I withdraw myself to safety!’. The matter was thus irrevocably closed. Indeed, Hitler stated with some conviction that the Red Army would be destroyed at the very gates of Berlin.

Читать дальше