Logistics for all the KSC people arriving at Barksdale and Lufkin was proving difficult. United Space Alliance’s Rikki Ojeda and Linda Moynihan were using their personal credit cards to hold rooms for KSC staff coming into town. Both had run up several thousand dollars of charges. I contacted Kennedy and requested more administrative assistance.

—

Massive search efforts proceeded despite cold temperatures and a steady rain throughout the debris field. Limited visibility restricted some air search operations, but ground crews continued to work. [28] Cohrs, “Notes,” 8.

Debris teams were asked to concentrate on locating reinforced carbon-carbon panels from Columbia ’s left wing, material from the shuttle’s outer mold line, supporting structure, and tile from the shuttle’s belly. Analysis of the telemetry implied the presence of hot plasma inside Columbia prior to the accident, but it was still unclear how it had entered the shuttle’s interior. Possible entry points included breaches in the left wing’s leading edge, the left landing gear door, or from missing tiles on the shuttle’s belly or underside of the left wing.

Despite the televised warnings about potential dangers, local residents were bringing in debris that they had collected. In the Lufkin Civic Center, astronaut Brent Jett called Ed Mango over to the astronauts’ table to show him one item that someone had dropped off. Mango identified it by its distinctive shape as the door to one of Columbia ’s star trackers—optical and electronic devices in the ship’s nose that were part of the navigation system.

Another citizen brought in one item that he had found at his child’s school. Mango instantly recognized that it was a pyrotechnic device. Not wanting to create a panic about a potentially armed and unstable explosive device in the middle of the command center, Mango nonetheless found himself backing away from the table, his face bright red. He thanked the citizen and sent him on his way. After he left, Mango called out, “I need a metal box, and I need it now!”

The collection centers continued to receive hazardous items from the field. When NASA started planning to ship the collected propellant tanks and pyros from Texas to Barksdale, regulations got in the way. Transporting potentially hazardous material across state lines was considered a violation of EPA regulations. Storing the material at Barksdale also exposed the air force to liability under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. After lengthy discussions and legal research, EPA eventually determined that it had authority to move hazardous debris from Texas to Louisiana, since both were officially declared emergency sites. [29] Shafer and LeConey, “Legal Issues,” 60.

By the evening’s check-in call, Carswell Air Station near Fort Worth reported 198 pieces of confirmed debris in their hangar, including a piece of the leading edge of the left wing, its underlying carrier panel, as well as other material from that wing. They also reported that the Civil Air Patrol in the Dallas area was actively supporting airborne search efforts.

More than one thousand pieces of debris had been located in Sabine County, with about four hundred cataloged. [30] Cohrs, “Notes,” 8.

The collection center in Nacogdoches was still receiving forty to fifty calls per hour about debris sightings.

Lufkin reported that two recovered nitrogen tetroxide tanks had been completely decontaminated. Six EPA technicians were exposed to hazardous chemicals during the cleanup. The armed pyrotechnic T-handle that had been turned in to Ed Mango was now secure in a munitions case.

Recovered pieces of the outboard elevon from Columbia ’s left wing came in to the Palestine hangar. Other reported finds included a harness, a boot, strips of clothing, and an eight-foot section that might have come from the shuttle’s left wing, with dozens of thermal tiles and heat sensors still attached. [31] Gettleman, “Shuttle Debris Theft.”

Several items from the avionics equipment area of the crew compartment were discovered in San Augustine County on Thursday. NASA used this information to request that a special team search the area northwest of Bronson on Friday for a classified box that had been in the same section of the shuttle’s avionics bay. [32] Cohrs, “Notes,” 9.

—

Searchers near Palestine found a videotape cassette on Thursday—one of many that at least partially survived Columbia ’s breakup. The tapes were collected and sent to Houston. Several days later, astronaut Ron Garan took them in his T-38 jet to the NTSB headquarters in Washington, DC, to see if any information could be recovered from the recordings.

Garan and an NTSB technician spent hours playing back the tapes, which in many cases were charred or damaged. Most were either blank or contained data from the scientific experiments in Columbia ’s Spacehab module. As midnight approached, Garan phoned Houston to report that he had seen nothing relevant to the accident investigation. After the call, he discovered that there was one more tape to check. He began playing it, and within a few seconds, he froze.

It was the cockpit video of Columbia ’s reentry.

“The hair stood up on the back of my neck,” Garan said, “because we didn’t know how long the video was going to last or what it was going to show.” To his relief, the tape ended several minutes before the first sign of trouble.

NASA publicly released the video on February 28. The tape showed Columbia ’s crew being happy, acting professionally, and enjoying the ride. They were passing the video camera around, smiling at one another, and remarking on the sight of the glowing plasma surrounding the orbiter. They were obviously unaware that anything was wrong with their ship. [33] NASA, “New Space Shuttle Columbia Images Released,” news release 03-212, June 24, 2003. Searchers eventually recovered nearly ten hours of video and ninety-two photographs with in-cabin, Earth observation, and experiment-related imagery. Of the 337 videotapes aboard Columbia , twenty-eight were found with some recoverable footage. Only twenty-one rolls of film out of the 137 rolls of film aboard the ship were found with recoverable photographs.

—

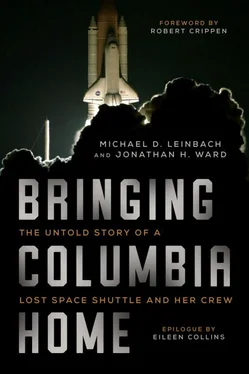

At nine in the morning, on Friday, February 7, Kennedy Space Center conducted its memorial service. Bob Crippen, Columbia ’s first pilot, delivered a moving eulogy for his beloved Columbia and her crew:

It is fitting that we are gathered here on the shuttle runway for this event. As Sean [O’Keefe] said, it was here last Saturday that family and friends waited anxiously to celebrate with their crew their successful mission and safe return to earth. It never happened.

I’m sure that Columbia , which had traveled millions of miles, and made that fiery reentry twenty-seven times before, struggled mightily in those last few moments to bring her crew home safely once again. She wasn’t successful.

Columbia was hardly a thing of beauty, except to those of us who loved and cared for her. She was often bad-mouthed for being a little heavy in the rear end, but many of us can relate to that. Many said she was old and past her prime. Still, she had only lived barely a quarter of her design life. In years, she was only twenty-two. Columbia had a great many missions ahead of her. She, along with the crew, had her life snuffed out in her prime.

There is heavy grief in our hearts, which will diminish with time, but it will never go away, and we will never forget.

Hail Rick, Willie, KC, Mike, Laurel, Dave, and Ilan.

Читать дальше