In June 2002—just prior to Columbia ’s originally scheduled July launch date—Ann received a birthday package from Dave while visiting family in Connecticut. Inside was an empty watch box. Fearing that the watch had been stolen, she looked more carefully and found a note taped to the lid, which read, HELP! I’M BEING HELD HOSTAGE ABOARD THE SPACE SHUTTLE! Ann was ecstatic to hear that Dave would be flying with her watch on the mission.

A few months later, Ann and Dave ended their romantic relationship, but they remained very close friends. She participated as Dave’s “stand-in spouse” at all of the traditional prelaunch activities attended by the crew’s spouses and families.

—

Columbia , like her sister shuttles, lived at Kennedy Space Center when she was not in orbit. An orbiter might fly three times in a year, for an annual total of five to six weeks in orbit. The rest of the time, our ground teams at Kennedy took care of it.

Our people knew the actual flight hardware better than anyone—the whine of every cabin fan, the condition of every tile on the orbiter’s belly, the twists and turns of the fuel piping in the engine compartment—and hundreds of people at KSC lived with the orbiter every day for much of their careers. The orbiter only left our care during the ten to fourteen days it was in flight.

As a reusable vehicle, the shuttle had to be inspected, repaired, and maintained after each flight. Its complex systems meant that this was no easy task. No matter how well a shuttle performed on its mission and how good it looked after a flight, preparing it for its next mission was never as simple as giving it a quick once-over. Our workers spent tens of thousands of man-hours checking and maintaining every system, replacing damaged thermal insulation tiles, reconfiguring the crew compartment and payload bay for the requirements of the next mission, changing the tires, and performing myriad other tasks to ensure the shuttle continued to meet its incredibly stringent reliability and safety requirements.

All this meant that the hands-on workers at Kennedy—primarily the engineers and technicians of our main contractors United Space Alliance (USA) and Boeing—were intimately familiar with each nut and bolt, wiring harness, coolant pipe, and every single one of the hundreds of thousands of parts on board the orbiter.

Columbia was a little different from her sister orbiters. As the first shuttle constructed for spaceflight, her structure and internal plumbing were unique. She had a different tile pattern and air lock, and she carried instrumentation that the other orbiters lacked. She was eight thousand pounds heavier than her sister ships. The differences were subtle, but they were significant enough that technicians who serviced the other three orbiters sometimes became frustrated if they were called over to work on Columbia . She developed a reputation at Kennedy for being the beloved black sheep of the fleet.

Rather than apologizing for her, the dedicated Columbia processing teams rallied around “their” ship and became even more close-knit as a consequence. They loved Columbia and her quirks. Many people specifically requested to work on Columbia because of her status as the flagship of the fleet.

Quality inspector Pat Adkins said: “You can’t actually put into words exactly how you feel about a spacecraft. You use it, you learn it—you know where all its little idiosyncrasies and scars are. You know its weak spots, its strong points. They were all different. If you talk about a mission and don’t talk about the spacecraft like an eighth member of the crew, it’s like trying to tell the story of Star Trek without the Enterprise .”

We all knew how he felt. Columbia was just as “alive” to us as the people who flew her.

Astronauts typically spent most of their time in Houston training for their upcoming mission. Unlike the Apollo and earlier missions, where each space capsule only flew once, shuttle crews did not have a spacecraft that was uniquely “theirs.” They could not work with their assigned vehicle until it returned from its latest mission. There were also no training simulators at KSC. The commander and pilot occasionally came to town to practice landing approaches in the Shuttle Training Aircraft at the KSC runway, but most of the crew usually did not visit Kennedy until their mission drew near.

STS-107 was an exception in that the facility where the Spacehab module was being prepared for the mission was located outside the southernmost security gate on the air force side of the property occupied by NASA and the air force. Marty McLellan, Spacehab’s vice president of operations, set aside a desk for Rick Husband decorated with a HOME SWEET HOME plaque, because the crew was in town so frequently to train with the equipment.

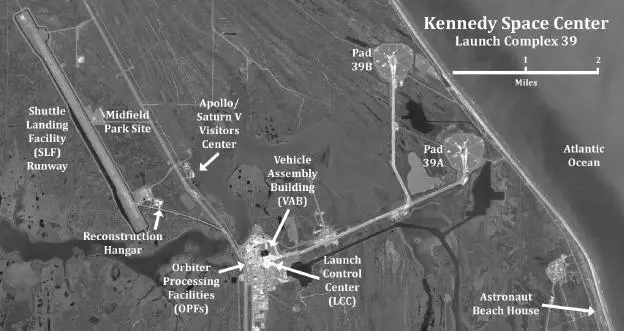

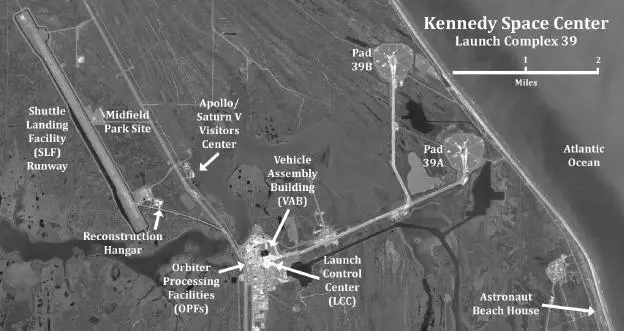

While the astronauts were training, the shuttle was being prepared in an Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF)—one of three hangars adjacent to KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). [5] Each one of the four orbiters was in a constant state of flux—undergoing maintenance, being “de-configured” after returning from a mission, being prepared for an upcoming mission, being tested, being stacked, sitting at the launchpad, flying a mission, or being upgraded for safety and/or performance reasons. There were three hangars and four orbiters, occasionally requiring one of the vehicles to sit in an empty bay in the Vehicle Assembly Building while awaiting space in a hangar.

The shuttles spent more time in the OPF than anywhere else. In those special hangars, some teams worked in the aft end of the vehicle to replace the engines and service the propulsion systems. Other teams worked to reconfigure the cargo bay and the crew compartment for the requirements of the mission.

Part of preparing for a mission included a “crew equipment interface test”—more of a weekend-long activity than an actual “test.” The usual processing activities in the OPF were shut down and distractions were minimized, so the astronauts could spend time with the payload and the orbiter to get a feel for the configuration of their vehicle. Practicing in the simulators and the mock-ups at Houston was no substitute for the crew putting their hands on the actual flight hardware and seeing where everything was going to be stowed in the ship.

Pat Adkins remembered Columbia ’s crew arriving with happy confidence on June 8, 2002. He said, “They were all smiles, especially Willie McCool. His was the biggest! As they passed by me, I looked them in the eyes and promised, ‘We’ll give you a good ride!’” [6] The STS-107 crew also ran an interface test in June 2001, before the STS-109 mission was moved ahead of STS-107 in the launch schedule. STS-107’s experiments were removed from the payload bay, replaced with Hubble Space Telescope servicing equipment, and then placed back into the payload bay after Columbia returned from the STS-109 flight.

The crew inspected the orbiter and checked out everything with which they would be working in orbit. The astronauts noted which cables were routed to which equipment items and looked behind panels and under the mid-deck floor. The crew requested that Velcro strips or stickers be put where they wanted them in the cabin. These strips would anchor cue cards, timers, and other items once the shuttle and her crew were weightless. It was the first time that many of the KSC ground support team worked directly with the astronauts for the mission. At the end of the activity, the astronauts and the ground workers posed for a picture together. It was an especially exciting moment for our processing team. Afterward, the astronauts and several of the KSC workers gathered at a local restaurant for food, drinks, and fellowship.

Читать дальше