The US Forest Service secured permission to resume helicopter flights over the area. Don Eddings of the Sabine Ranger District flew as a spotter in a contracted Bell 205 helicopter. His goal was to locate and record the position of possible crew remains and debris in inaccessible locations. As his helicopter flew between Bronson and Spring Hill Cemetery, something on the ground reflected the morning sun. He asked the pilot to land nearby, and Eddings found a large plastic envelope fastened with Velcro. Curious, he opened the envelope. It contained what appeared to be Columbia ’s flight plan. He marked the location and called it in for pickup.

In Lufkin, astronaut Jim Wetherbee contemplated his responsibility for recovering Columbia ’s crew. His assignment was clear: Find the remains of the crew. Do whatever it takes. There are no rules.

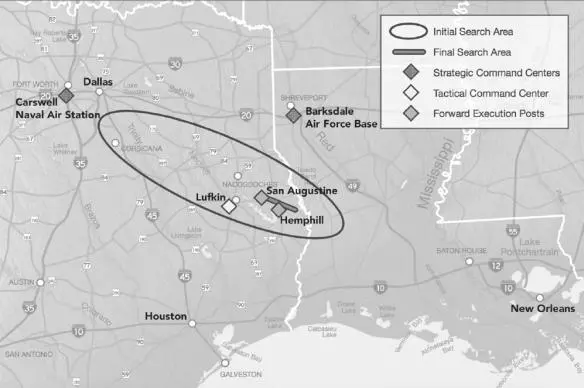

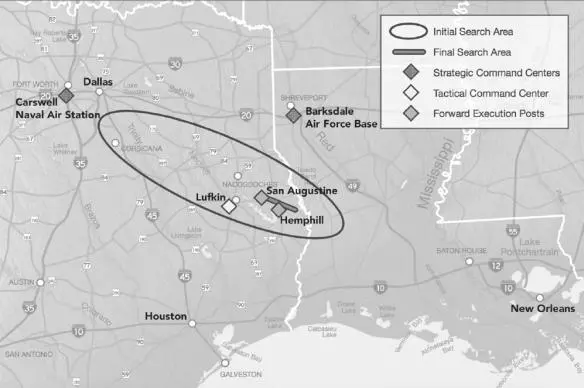

The potential scale of the search effort required seemed almost impossible to comprehend. Analysis of the tracking data during Columbia ’s descent and breakup showed that debris rained down over a three-hundred-mile-long, fifty-mile-wide path stretching from Dallas to Fort Polk, Louisiana.

With locally led searches already underway in East Texas, Wetherbee established a military-style command and control system, led by astronauts, to solidify the search operations. John Grunsfeld was “ground boss” in Lufkin, charged with planning the ground searches each day, coordinating the search teams, and using feedback from the field to refine the overall strategy for subsequent days. He was also responsible for narrowing the search field based on analyses of recovered material.

Scott Horowitz, as the “air boss,” managed all airborne searches for the crew. [5] Dom Gorie began alternating in this role with Horowitz several days into the recovery period.

Steve Bowen and Jim Reilly oversaw the water search operations in the lakes along the debris path. [6] US Navy, US Navy Salvage Report, Space Shuttle Columbia , Report S0300-B5-RPT-01 (Washington, DC: US Navy, Naval Sea Systems Command, September 2003), 1-7.

Marsha Ivins coordinated the administrative and logistical support operations for the astronaut office team in Lufkin. [7] Stepaniak, Loss of Signal , 21.

Their leadership operations were completely separate from the activities associated with retrieving Columbia ’s debris. Wetherbee and his team did not discuss their activities with the teams working on the debris recovery effort. Information did flow in the other direction, though, as locations of retrieved items from the crew module might help target people who were searching for the crew.

Map of East Texas showing the initial search area (ellipse) based on the first reported debris sightings. During the course of the following week, NASA gradually refined the search area for Columbia ’s crew to a narrow corridor between San Augustine and the Toledo Bend Reservoir.

As the day progressed, it became clear that search teams in Sabine County needed more GPS equipment. Over the next several days, the command center sent people to every Walmart, sports store, and outdoor outfitter within a 150-mile radius to purchase all the available handheld GPS devices. The team also bought $35,000 worth of equipment and supplies from Hemphill’s only office supply store. [8] Paul Keller, writer-editor, Searching for and Recovering the Space Shuttle Columbia: Documenting the USDA Forest Service Role in This Unprecedented ‘All-Risk’ Incident, February 1 through May 10, 2003, www.fireleadership.gov/toolbox/lead_in_cinema_library/downloads/challenges/Searching_Recovering_Shuttle_Columbia_2003_Paul%20Keller.pdf .

Other command center staff rustled up first aid supplies from the local pharmacies and the Walmart in Jasper.

Leaders of NASA’s command teams from Lufkin arrived at the Hemphill command center. They asked to see law enforcement officer Doug Hamilton from the US Forest Service, who had been photographing debris with his digital camera over the past two days. After reviewing his images with them in private, he drove them around to the locations of various items they wanted to examine firsthand.

Astronaut John Grunsfeld returned to the Hemphill command center to help plan searches for the crew. He mentioned to Olen Bean of the Texas Forest Service that his laptop lacked mapping software, so Bean offered to let him use a copy of a digital street atlas. Grunsfeld tried several times without success to get the program to load on his computer. Finally, Bean pointed out that Grunsfeld was hitting the “X” (close box) instead of “Yes” to complete the installation. Grunsfeld, a man with a PhD in physics—someone who had repaired and upgraded the Hubble Space Telescope on two separate missions—smacked his head and said, “Man! I’m so stupid!” It lightened the mood. But it also bore witness to the enormous pressure he was feeling.

Other astronauts arrived at the command center to help investigate sightings of possible human remains. Among them was Scott Kelly, Mark’s identical twin brother.

Shortly after noon, the command center in Hemphill received a call that a crew member’s body had been found deep in the woods near the Yellowpine Fire Tower, in an area known locally as Seven Canyons. The landowners searched their property that morning using all-terrain vehicles and found the remains near the boundary of Sabine National Forest. [9] Byron Starr, Finding Heroes: The Search for Columbia’s Astronauts (Vancouver, Canada: Liaison Press, 2006), 50.

Mark Kelly, Terry Lane, and two Texas game wardens went to the property to investigate. The landowners led them through the dense forest. It took nearly half an hour to reach the site using the ATVs. Kelly and his team saw the astronaut’s body lying on a small mound in a clearing almost one mile from the closest roadway. The beauty of the surroundings belied the tragic nature of the situation. Kelly and Lane sat with the fallen astronaut for almost ninety minutes as they awaited the arrival of the rest of the recovery team.

Brother Fred Raney delivered a prayer, and the FBI documented the scene. While the recovery was in process, a call came in that another body had been located about five miles away, on the other side of Hemphill. This sighting was near Housen Hollow Lane, west of Farm Road 2024. After carefully bringing the crew member’s remains out from the deep woods at Yellowpine, the recovery team headed off toward the Housen Bayou site.

Television satellite trucks massed along the street across from the Hemphill Volunteer Fire Department’s fire hall. The command center was cordoned off, but incident commanders had difficulty entering and leaving the building undisturbed. Co-incident commanders Sheriff Maddox and Billy Ted Smith in particular were being closely watched. They had to resort to stealthier tactics—changing shirts or jackets, leaving through the back entrance of the fire hall, or using decoy vehicles—just to get their work done.

To be fair, the national newspapers and television outlets showed respect by not sensationalizing information that might be upsetting to the families or to NASA. Still, they were eager to tell the world—and the world wanted to know—what was going on in this high-profile search-and-recovery operation. They pushed the boundaries until they were told to back off. Reporters attempted to follow searchers out into the field. Police sometimes had to hold them back to keep them from interfering.

Much to the relief of the incident commanders, the local populace was circumspect about sightings of human remains on their property—calling the command center, not the press. To this day, the people of Sabine County will not discuss with outsiders what they saw of the remains of Columbia ’s crew.

Читать дальше