Ed Mango, my assistant launch director, had supported “Hoot” Gibson and Jerry Ross’s STS-27 mission early in his career at NASA. Recalling how badly beat up Atlantis was on that mission, Mango expected that Columbia would also make it back to the landing site, but would probably be heavily damaged. He requested permission in advance to go out to the runway after the vehicle was “safed” so that he could inspect the ship personally.

Ann Micklos said, “Putting on my engineering hat, we were interested to see what the vehicle was going to look like when it came back. I thought she could handle reentry with the damage. I trusted the team that provided the ‘go for entry.’ However, our team was also planning how we were going to turn the vehicle around on the ground to get it ready for [missions to the International Space] Station. None of us in our wildest thoughts believed that things would turn out the way they did.”

Pressure to keep on schedule had combined with a complacency brought about by so many past mission successes. The same conditions were present for Apollo 1 and Challenger . And once again, a crew would pay with their lives.

Chapter 4

LANDING DAY

8:15 a.m. EST

As Saturday, February 1, 2003, dawned, NASA teams at Kennedy Space Center and Johnson Space Center prepared to bring Columbia home at the end of her sixteen-day mission. Orbiting 173 miles above Earth, [1] NASA, STS-107 Shuttle Press Kit (Houston, TX: NASA, December 16, 2002), 17.

Columbia ’s crew stowed their experiments in lockers and closed and latched Columbia ’s payload bay doors. The crew donned their launch and entry pressure suits and helmets. These orange “pumpkin” suits could provide protection and oxygen in case the cabin lost pressure during reentry or the crew had to make an emergency bailout. [2] NASA added the Inflight Crew Escape System to space shuttles after the Challenger accident. Starting when the shuttle was at about thirty thousand feet in altitude, the astronauts could depressurize the crew module, jettison the hatch, and then extend an escape pole through the opening in the fuselage. One by one, the astronauts would hang a strap on the pole and slide out through the hatch. Their individual parachutes would open once they were clear of the shuttle. It took about ninety seconds to get the crew out this way, by which time the orbiter was at an altitude of ten thousand feet (“Everybody Out!” NASA Educator Feature, https://www.nasa.gov/audience/foreducators/k-4/features/F_Everybody_Out.html ). This process would occur over the ocean, where the shuttle would be ditched.

The astronauts took their positions in the crew module. On the flight deck, Rick Husband sat in the commander’s seat, with pilot Willie McCool to his right. Kalpana Chawla sat in the jump seat, behind and centered between Husband and McCool. To her right was Laurel Clark. These four astronauts had the best view during reentry, as all of the shuttle’s large windows were on the flight deck. The three crewmen seated in the shuttle’s mid-deck (seated from left, Mike Anderson, Dave Brown, and Ilan Ramon) could see only the stowage lockers directly in front of them.

Columbia could land either at Kennedy or at Edwards Air Force Base in California, depending on the weather in Florida. NASA had to make the landing site decision about two hours in advance, because the de-orbit burn needed to happen halfway around the world from the landing site and one hour before touchdown.

The weather forecast at Kennedy looked favorable, so Commander Husband was given the “Go” to come home to KSC. He fired Columbia ’s orbital maneuvering system engines over the Pacific Ocean at 8:15:30. This would drop the ship out of orbit and direct her toward Florida, with a touchdown at 9:16 Eastern Time. She would come in to Kennedy’s Shuttle Landing Facility—the SLF—one of the world’s longest runways.

Columbia gradually fell out of orbit and became an unpowered glider in the atmosphere. Now irrevocably committed to land at KSC, there was no option to go around again or look for another spaceport.

Launch and Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain and his Flight Control team in Houston were managing the last stages of the flight. They monitored telemetry from the vehicle and communicated with the crew. They would continue to command the mission until Columbia ’s crew disembarked at Kennedy.

Outside Mission Control, the rest of Johnson Space Center was almost a ghost town as this cool, foggy day dawned. People who were not involved in mission operations for Columbia or the International Space Station were at home for the weekend. Andy Thomas, deputy chief of the astronaut office, was on routine duty in Building 4 South that morning, manning the contingency action center. There would normally be very little for him to do.

I arrived at Kennedy’s Launch Control Center at seven o’clock to monitor the de-orbit burn. Ed Mango was there, as was Don Hamel, controlling Kennedy’s landing operations. Mango came in that morning to fill in for a vacationing colleague. He told his wife to expect him home by ten-thirty, after Columbia was securely in the hands of the landing and recovery team. Our main role as managers was to deploy the landing and recovery forces to assist the crew and power down Columbia after she landed. Nearly two hundred people crowded into the Firing Rooms on launch day. But on landing day, things felt almost deserted, with only about fifty people on hand.

I watched the proceedings on one of my computer monitors, and I saw that the de-orbit burn occurred on schedule and without problems. I then raced out to the Shuttle Landing Facility runway, about two miles north, to join other VIPs and guests gathering to greet Columbia . I did not want to get stuck waiting for the convoy of landing support vehicles to trundle across the roadway. They had also departed their staging area for the runway when they heard that the de-orbit burn was successful.

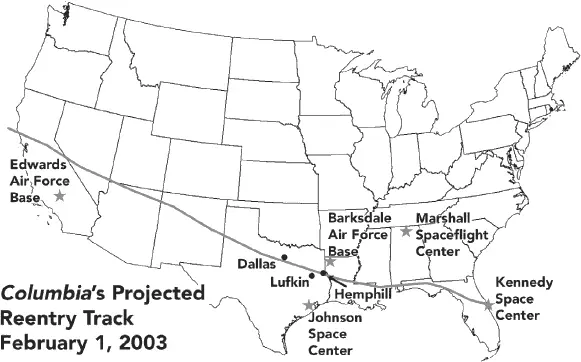

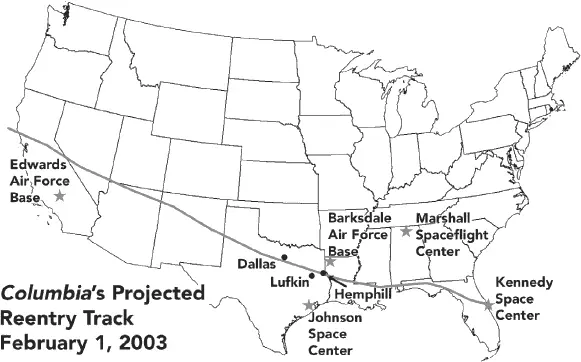

Columbia began encountering the upper reaches of the atmosphere. Her path would take her east-southeast across California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Louisiana. Then she would skirt the Gulf Coast as she lined up for the approach to the runway.

As she made her way across the southern United States over the course of twenty minutes, Columbia would lose her last forty-four miles in altitude and slow from sixteen thousand miles per hour to zero at “wheels stop.” Columbia ’s automated flight control system ran all aspects of the flight during reentry, banking and rolling the orbiter to control its speed and energy profile during the period of maximum heating. Rick Husband would take the control stick only in the final couple of minutes of the approach and landing sequence.

Columbia ’s projected reentry path over the United States. Contact was lost with the ship just after it passed south of Dallas.

8:30 a.m. EST

Landing day at Kennedy Space Center was invariably a happy occasion, and the mood was much less tense than for launch. While both launches and landings were cause for celebration, crew families understandably held their breath and prayed during a shuttle’s ascent to orbit. It was impossible to forget the Challenger accident, so launches were always accompanied by unspoken fears that the families might never see their loved ones again. In contrast, landing day meant eager anticipation for the approach of the shuttle, followed by jubilation, pride, and relief when the orbiter’s wheels came to a stop on the runway.

Читать дальше