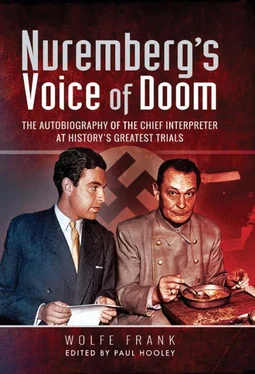

Wolfe Frank.

1. EARLY LIFE AND FORMATIVE YEARS

THERE IS, IN THIS OPENING CHAPTER, a considerable lack of the kind of details usually reported at the beginning of a biographical tale.

I never had the slightest interest in ancestry and family trees, but it seems clear, on the strength of sketchy documentation, that my grandfather [1] Albert Frank (1835–1894), Wolfe’s grandfather, was an industrialist and head of the metal-ware company of the same name. The company was well known for the manufacture of parts for automobiles and bicycles and a wide range of lanterns that bore the company’s well-known ‘Muncher Kindl’ (Munich Child-Angel) logo.

was a Jew and his wife was not.

I knew my father [2] Wolfe’s father, Ferdinand Frank (1866–1933), was the son of Albert Frank and his wife Bertha (née Pappenheimer). He took over as head of the family business following his father’s death and floated it on the Berlin Stock Exchange in 1914 under the name Frankonia AG on the expectation of large military orders (see photographs of Frank family and the Frankonia factory at Plates 3–5). The company had factories in Beierfeld, Berlin-Adleshof and Elbing. Prior to his marriage to Wolfe’s mother (Ida) Ferdinand had been married to, and divorced from, Alice Frank (née Rosenbaum) who later died in a concentration camp. The couple had two children Maria, who also died in a concentration camp, and Olly. Busts of these two children were carved in the home that Ferdinand had designed – possibly by the famous German architect Erich Mendelsohn – and built in Beierfeld (see Plate 6).

only as an atheist who paid taxes to the local church and had dual British/German nationality. No evidence now exists of either, and my attempts to trace his British citizenship ended in failure – I only have his word for it. He was, at one time, a wealthy industrialist but he died, a suicide, without leaving any assets worth mentioning.

Mother [3] Wolfe’s mother, Ida Therese Frank (née Hennig), was born in 1879 in Leipzig. She was the daughter of a retired Gas Inspector. Ferdinand and Ida were married at the Register Office, Hackney, London, on 9 April 1908. At the time of the marriage Ferdinand was residing at the Cecil Hotel in the Strand and Ida at 10 Portland Road, Finsbury Park. A fortnight later, on 24 April, the couple were also married in Munich.

was totally angelic, very beautiful in her younger days and very superstitious. Consequently, she apparently managed to persuade the local registrar to record my birth [4] Wolfe was originally named Johann Wolfgang Frank, and then Hans Wolfgang Frank. He later became Hugh Wolfe Frank – the name under which he was granted British passports and, in 1948, British citizenship – however he preferred to be known as Wolfe Hugh Frank or just plain Wolfe Frank.

in 1913 as being in the early morning of Saturday, 14 February when, in reality, I had appeared during the closing hours of Friday 13th! I cannot, of course, judge whether my mother’s white lie brought me luck, but it certainly brought me many Valentine’s cards!

My school years [5] Wolfe attended an elementary school in Beierfeld and Grunewald Gymnasium in Berlin, a grammar and boarding school for boys, until ‘Mittlere Reife’ (pre-college examination).

did not produce any remarkable achievements or events. They were lived at Villa Frank in the small village of Beierfeld, Saxony, where I was born, and later in Berlin and they were, generally, happy years.

Sex, in those days, was a closed book of mysterious, hidden things that we could not imagine.

When one of my playmates, who was two years older than the rest of my group, had his first brush with sex he claimed that, ‘It is nowhere near as nice as you imagine when you masturbate’, we were, all of us, very disappointed and we decided to put things off until the distant future.

I had a shattering clash with reality, however, when I was about fifteen years old. A voluptuous soprano, in her mid-thirties, of the Munich Opera, kidnapped me to her apartment and performed fellatio upon me as I was standing before an upright piano playing airs. I was terribly shocked and enjoyed none of it, simply because I had no clue as to what it was all about.

A little later, my father became involved in a serious affair with his secretary (which lasted until his death in 1933). I remember going to a musical revue in Berlin during that period – it must have been around 1929, so I would have been sixteen. My best school friend and I had heard that there were girls dancing topless. They were indeed, but we found the sight uninteresting.

That night however we spotted my father in the front row, holding hands with a blonde – who was not his mistress. I felt fairly confused because he had already inflicted much suffering on my mother when he took up with his secretary. Now here he was clearly working on yet another alternative. Father was home when I returned, and he began to berate me for being out late without his permission. ‘I was at the Admiralspalast,’ I said. He never assaulted me again with disciplinary action, but he still managed to make some most uncomfortable contributions to my upbringing. He refused to let me study engineering when I left school, but sent me to a large factory for ‘practical technical training’. For nine months I had to rise at 04.30 hours, travel for an hour and-a-half and return at 18.00 hours. My ‘technical training’ was later continued in a municipal training workshop [6] Berlin Institute for Practical Mechanics.

– but it was never finished, because I ran away from home when I was 18-years-old.

I had one last terrible clash with father over his mistress whom I hated passionately, mostly out of love for my mother. In a fit of rage, I stuffed all her belongings – she was living with us by then – into suitcases and cardboard boxes and threw them into the street. Father decreed, ‘Commitment to a home for wayward boys’ but I didn’t wait around. I hurriedly left Berlin for Munich and went ‘underground’ as an apprentice in the BMW Motor Works where love came into my life for the first time. However, the lady was snatched away by my best and much older friend and this resulted in an unsuccessful suicide attempt.

I had had no contact with my father after I left Berlin, but he promised an uncle of mine that he would leave me in peace and ‘Un-committed to any penal institution’. The road was clear and, having got suicide and such out of my youthful and immature system, I started to enjoy life.

I was fired by BMW for ‘Improper conduct towards a superior’. My ‘technical’ training included an unreasonable amount of workshop sweeping and I had suggested my ‘superior’ should sweep away some of his own shit. This led to my sacking and then my appointment, aged nineteen, as a car sales trainee at the Munich showrooms of the (now defunct) Adler Works. I also borrowed some money and bought and sold cars on my own account.

One such vehicle provided me with the opportunity to meet my father for what was to be the last time. The car was a 2.4 litre Bugatti – white and blue and beautiful. I had sold it to a firm of dealers in Berlin who wanted a rapid delivery. Before leaving, and on the spur of the moment, I phoned my father and suggested we meet at the Cafe Kranzler on Kurfürstendamm , to which he agreed. The car broke down on the way and, although I drove like a madman, I was forty minutes late. As I approached Kranzler I was truly apprehensive. Father was a fanatic regarding punctuality. My reconciliation attempt seemed doomed to failure. However, when I arrived he was still there, immaculately and severely dressed in elegant black jacket, striped trousers, grey vest and wing-collar. He was radiating censorious displeasure. Then, he saw the car and, as I extricated myself from it, he came over to me. ‘Leave the keys’ he said, as an opener. Then he got into the Bugatti and roared off up the Kurfürstendamm.

Читать дальше