As by accident, the main revivalist of that "great zeal", Bailly, was an

"Assumptionist", or, in fact, a camouflaged Jesuit. As for the rack and the thumb-screws, we could have reminded the good Father that these instruments of torture are in the tradition of the Holy-See and not the one of the republican state.

Finally, the congregations paid—about half of what they owed—and the aforementioned Abbe admits that "the prosperity of their work was not impaired", as we can well imagine.

We cannot go into details concerning the laws of 1880 and 1886 which tended to assure the confessional neutrality of the state schools, this

"secularisation"(67a) which is natural to all tolerant minds, but is rejected by the Roman Church as an abominable attempt at forcing consciences, something she has always claimed for herself. We could expect her to fight for this so-called right as violently as for her financial privileges.

(66) and (67) Abbe Brugerette, op.cit., pp. 185,196,191.

(67a) See Jan Cotereau: "Anthologie des grands textes laiques" (Fischbacher, Paris)

94

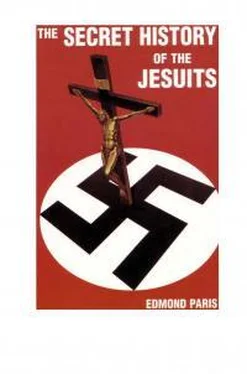

THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE JESUITS

In 1883, the Roman congregation of the Index, inspired by Jesuitism, enters the fight by the condemnation of certain school books on moral and civic teaching. Of course, the matter is grave: one of the authors, Paul Bert, dared to write that even the idea of miracles "must vanish before the critical mind!" So, more than fifty bishops promulgate the decree of the Index, with fulminating comments, and one of them, Monseigneur Isoard, declares in his pastoral letter of the 27th of February 1883 that the teachers, the parents and the children who refuse to destroy these books will be barred from the sacraments.(67b)

The laws of 1886, 1901 and 1904, declaring that no teaching post could be held by members of religious congregations, also started a flood of protestations from the Vatican and the "French" clergy. But, in fact, the teaching monks and nuns only had to "secularise" themselves. The only positive result of these legal dispositions was that the professors of the schools "so-called free" had from now on to produce adequate pedagogic qualifications, a good thing when we know that, before the last war, the catholic primary schools in France numbered 11, 655 with 824,595 pupils As for the "free" colleges, and especially the Jesuits', if their number is being reduced it is because of several factors which have nothing to do with the legal wrangles. The superiority of the university's teaching, acknowledged by the majority of parents, and, more recently, its being without change, are the main causes for its growing popularity. Besides, the Society of Jesus has voluntarily reduced the number of its schools.

(67b) See Jean Cornec: "Laicite" (Sudel, Paris).

95

Section IV

Chapter 8

The Jesuits and General Boulanger

The Jesuits and the Dreyfus Affair

The hostility of which the devout party pretended to be the victim, at the end of the 19th century, from the Republican state, would not have lacked justification, even though this hostility, or more accurately mistrust, had been even more positive. In fact, the clerical opposition to the regime which France gave herself freely showed itself at every opportunity, according to the Abbe Brugerette. In 1873, the attempt to restore monarchy with the Count of Chambord failed, even though strongly supported by the clergy, because the Pretender stubbornly refused to adopt the tricoloured flag, to him the emblem of Revolution.

"Such as it is, Catholicism seems bound to politics, or to a certain kind of politics... Loyalty to the Monarchy was transmitted from generation to generation in the old noble families as well as in the middle-classes and the common people, in the Catholic regions of the West and South. Their nostalgia of an ancient and idealised Regime, pictured in an epic Middle Age was coupled with the wishes of fervent Catholics whose main preoccupation was the salvation of the religion; they rallied, behind Veuillot, with the legitimate and devout royal family of Chambord, considered to be the form of government most favourable to the Church. Out of the union of these political and religious forces was born, in the strained situation after the war, a kind of reactionary mysticism, illustrated perfectly by Monseigneur Pie, bishop of Poitiers, and its best incarnation in the ecclesiastical world: "France, who awaits another chief and calls for a master..., will again receive from God

"the sceptre of the Universe which fell from her hands for a while", on the day when she will have learned anew how to go down on her knees".(68) This picture, described by a Catholic historian, is significant. It helps to understand the moves which followed, a few years later, the unsuccessful (68) Adrien Dansette, op.cit., II, pp.37, 38.

96

THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE JESUITS

restoration attempt of 1873.

The same Catholic historian describes in the following manner the political attitude of the clergy at that time:

"At election time, the presbyteries become centers for the reactionary candiates; the priests and officiating ministers make home-calls for the electoral propaganda, slander the Republic and its new laws on teaching they declare that those who vote for the free-thinkers, the present government or freemasons described as "bandits", "riffraffs" and "thieves", are guilty of mortal sin. One declares that an adulterous woman will be forgiven more easily than those who send their children to lay schools, another one: that it is better to strangle a child than give support to the regime, a third one: that he will refuse the last sacraments to those who vote for the regime's partisans. The threats are carried out: republican and anticlerical tradesmen are boycotted; destitute people are refused any help and workmen are dismissed".(69)

These excesses from a clergy affected more and more by Jesuitic ultramontanism are even less acceptable from the fact that they emanate

"from ecclesiastics paid by the government, as the Concordat is still enforced".

Also, the majority of public opinion is not happy at all with this pressure on the consciences, as the aforementioned author writes:

"As we have seen, the French people, as a whole, is indifferent to religious matters, and we cannot mistake the hereditary observance of religious practices for a real faith... "The fact is that the political map of France is identical to her religious map... we can say that in the regions where faith is strong, the French people vote for Catholic candidates elsewhere, they consciously elect anticlerical deputies and senators... They do not want clericalism, which is ecclesiastical authority in the matter of politics and commonly called "the government of priests".

"For a large number of Catholics, the fact that the priest, this troublesome man, interferes through the sermon's instructions and the confessional's prescriptions in the behaviour of the faithful, checking thoughts, sentiments, acts, food and drink, and even the intimacies of married life, is enough; they intend, at least, to limit his empire by preserving their independence as citizens".(70) We would like to see this spirit of independence as lively today.

But, even though the opinion of that "large number of Catholics" was such, the ultramontanes would not disarm and pursue, at every opportunity, the fight against the hated regime. They thought for a white that they had found the "providential man" in the person of General Boulanger, minister for War in 1886, who, having organised his personal (69) and (70) Adrien Dansette, op.cit., II, pp.46, 47, 48.

THE JESUITS AND THE DREYFUS AFFAIR

97

propaganda extremely well, looked like being a future dictator.

"A tacit agreement", wrote M. Adrien Dansette, "is established between the general and the Catholics, and becomes clear during the summer... He has also concluded a secret agreement with royalist members of parliament such as Baron de Mackau and Count de Mun, faithful defenders of the Church at the Assembly...

Читать дальше