In these circumstances the capture of Jalalabad was supposed to be the answer.

By early 1987 General Akhtar and I were confident, that it was only a matter of time before the Soviets quit Afghanistan. 1986 had witnessed Gorbachev’s bleeding wound speech, their offer of a four-year withdrawal timetable, the actual withdrawal of six regiments and the introduction to the battlefield of the Stinger. We began to discuss an operational strategy to cover this event and to bring the war to a successful conclusion after they had gone. General Akhtar’s relations with the Americans were somewhat cold and formal. He told me on several occasions that he did not trust the US to continue to support the Jehad wholeheartedly if the Soviets withdrew. I was inclined to agree, as I knew their antipathy towards fundamentalism and their desire for a moderate-nationalistic postwar government in Kabul.

One of the most difficult decisions that a guerrilla commander has to make once his forces begin to get the upper hand is the precise moment in the campaign when he should go on the offensive, when he should progress from guerrilla to conventional strategy and tactics. It is a matter of shrewd judgement. He has to assess the enemy’s position with care. Is he sufficiently weakened numerically and materially? Is he demoralized, collapsing from within? Does he lack the means to keep his units adequately supplied? If the answer to these questions is yes, then perhaps the time is ripe to shift to the conventional phase of guerrilla war. But before doing so the commander must also examine his own forces. Are his men sufficiently trained to adopt coordinated conventional attacks, and if so on what scale? Are they well equipped with heavy support weapons? Can they cope with the enemy’s likely control of the air? Can the scattered groups be supplied, concentrated, and then cooperate in joint offensives? Again if the answers are affirmative, then, probably, it is time to launch the offensive that will end the war.

There are numerous instances in military history when the guerrilla commander has moved into the conventional phase too soon, got a bloody nose, and as a result the campaign has been set back for months, even years. General Giap made this error in the early fifties against the French. The Communist Tet offensive in early 1968 in Vietnam failed, with losses of around 45,000 men, because their assaults were badly coordinated, communications were poor, the South Vietnamese Army fought well, and there was no demoralization within it ranks, or among the South Vietnamese population. Both the French and Americans lost eventually, but their opposing high commands had misjudged the timing of raising the stakes.

General Akhtar and I had considered this matter and decided that, even without the Soviet ground forces, it would be too risky to switch to a conventional strategy. Before General Akhtar was promoted away from ISI we had formulated an operational strategy to be applied during, and after, a Soviet withdrawal. Its objective was collapse in Kabul. If the people of Kabul, if the Afghan Army in Kabul, gave up, the war was won; but we did not feel this would be possible by direct assault. Kabul must be cut off, starved of food, fuel, men and munitions; the garrison must be demoralized and deprived of the means to fight. Then, and only then, were we confident they would surrender or turn on their Communist leaders. We did not consider the Mujahideen were ever likely to be ready for a conventional attack, or that one was necessary. We agreed that the strategy of a thousand cuts should continue, but with the emphasis on Kabul and its supply lines.

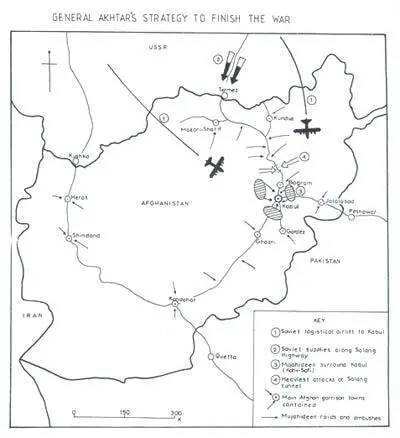

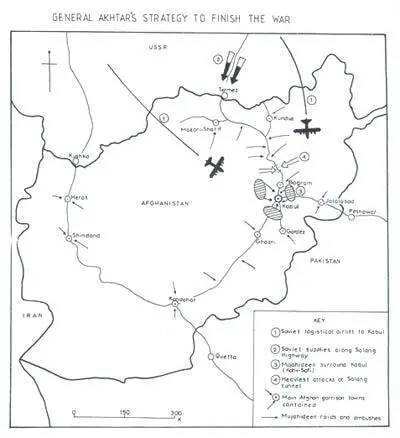

Map 22 shows what we had in mind. Kabul was to be surrounded by Mujahideen bases from which attacks were to be continuous. The Koh-i-Safi area would provide the main base for our efforts against Kabul which had to be made unusable. A series of blocking positions were to be established along all the main lines of communication from the Soviet-Afghan border to Kabul and Kandahar to deny logistic support to the Afghan regime. The strongest blocking positions were to be around the Slang Tunnel, the choke point for Kabul. We hoped that threats there would draw out forces from Kabul to clear the route, thus providing us with good ambush opportunities. Finally, the Mujahideen would contain and fix, as distinct from assault and capture, all the remaining Afghan garrisons in Afghanistan.

We could not of course decide on the timings for implementation as these would be dependent on the Soviets’ withdrawal time frame, the weather (winter), and on our being able to bring forward our logistic requirements to the right places. Before we could take this strategy further General Akhtar left ISI and I retired in August, 1987. April, 1988, saw the Ojhri camp disaster; the Soviet withdrawal started the following month; President Zia and General Akhtar died in the air crash in August; the US cutback on arms supplies started; the 1988-89 winter was particularly severe. The Soviets had gone by mid-February, 1989, and in March the Mujahideen took to conventional warfare with a full-scale assault, not on Kabul, but on Jalalabad.

Why was such an attack mounted? Why was there no strategic plan to finish the war after the Soviets had gone? These questions are difficult to answer. Part of the problem was the euphoria, the elation, that gripped everybody at the prospect of imminent, easy victory. Certainly the Mujahideen Leaders and Commanders made the fatal mistake of assuming that the Communist government would collapse by the middle of 1989, that without the Soviets’ presence its defeat was inevitable. This attitude was enhanced by the fact that most Mujahideen were busy making postwar plans and political manoeuvring. The Afghan Interim Government (AIG) had been formed in December, 1988, and was sitting in Peshawar. Although unrecognized internationally, its members saw themselves as about to take over in Afghanistan within a matter of months. Peshawar politics became more important than military operations. There was a feeling that Peshawar was the place to be, securing a position in the AIG rather than asking life and limb in the field when the war was all but won.

The AIG, which was basically controlled by the seven Parties, backed be Pakistan, and seemingly with the support of ISI, selected Jalalabad IS their target of their post-Soviet strategy. It was to be a conventional attack on a major city note 12 Note12 but not the key city of Kabul

. The time had come. so they thought, to abandon guerrilla warfare. Jalalabad was tempting because it was so close (50 kilometres) to the Pakistani border of the Parrot’s Beak. This meant that Mujahideen reinforcements and supplies should have quick and easy access to the front line. A main road led over the Khyber Pass to Peshawar. A victory at Jalalabad would enable the AIG to move forward with ease to Jalalabad. There they could declare a part of Afghanistan liberated and a new government established. This political objective had some merit, but depended for its fulfilment on military success. Could the Mujahideen surround and storm the city, and if they did would the Afghan Army collapse, or would they just get bombed out of existence? Above all would the loss of Jalalabad also lead to the loss of Kabul?

I believe General Gul allowed himself to be persuaded that it was militarily a sound proposal, partly by some of his younger operational staff, partly by the Leaders, and also by pressure from the Pakistan government, who saw it as a way of shifting all the Peshawar politicians and their countless followers back into Afghanistan. The easy capture of smaller garrisons at Barikot, Azmar and Asadabad in the Kunar Valley added to the Mujahideen’s over-confidence.

Читать дальше