Internationally the Soviets had been vehemently condemned for their invasion. It had soured steadily improving relations with both the West and China, so to triple the size of their army in Afghanistan would certainly heighten the political outcry against the Soviet Union and boost the resolve of the US and others to sustain the Mujahideen. Economically the war was an enormous drain. Gorbachev was later to call it a ‘bleeding wound’. Not only were the Soviets funding their own forces, but with the local economy in ruins they had to fund the Afghan government and army as well. Then, as their scorched-earth strategy took effect and refugees swarmed into Kabul and other large cities, they had to provide food for thousands of civilians. Billions of roubles were needed from an already flawed Soviet economy. It was estimated that $12 million a day were required to keep the country and its war ticking over. Drastically to enlarge the strength of the occupying troops would be asking too much. In practical terms such an increase would have needed a much improved supply line from the north to Kabul, and one that was not subject to frequent attacks. The Salang Highway could not meet these requirements. All this was of some encouragement to me. If the enemy was fully committed militarily, then I knew exactly what we were up against; if there was unlikely to be massive reinforcement, I surmised the Soviets might have no trumps in their hand.

I already knew there was a political as well as military side to the Soviet strategy. The Kremlin, and indeed the Soviet General Staff, understood the fundamental truth that without Pakistan the Jehad was doomed. When President Zia, acting on the urging of General Akhtar, offered Pakistan as a secure base area, he condemned the Soviets to a prolonged counterinsurgency campaign that they were ill-prepared to fight. Like all armies, guerrilla forces cannot survive indefinitely without adequate bases to which they can withdraw from time to time to rest and refit. They need the means with which to fight, they need resupplying, they need to train and they need intelligence. Pakistan provided all these things to the Mujahideen.

For the Soviets this was extremely frustrating. By 1983 they had launched a well-coordinated campaign to make the cost to Pakistan of supporting the Afghan resistance progressively higher. Their aim was to undermine President Zia and his policies by a massive subversion and sabotage effort, based on the use of thousands of KHAD agents and informers. Every KHAD bomb in a Pakistan bazaar, every shell that landed inside Pakistan, every Soviet or Afghan aircraft that infringed Pakistan’s airspace, and there were hundreds of them; every weapon that was distributed illegally to the border tribes, and every fresh influx of refugees, was aimed at getting Pakistan to back off. The Soviets sought with increasing vigour to foment trouble inside Pakistan. Their agents strove to alienate the Pakistanis from the refugees, whose camps stretched from Chitral in the north all the way to beyond Quetta, almost 2000 kilometres to the south.

The border areas of Pakistan had grown into a vast, sprawling administrative base for the Jehad. The Mujahideen came there for arms, they came to rest, they came to settle their families into the camps, they came for training and they came for medical attention. At the time we in ISI did not appreciate how fine a line President Zia was treading. As a soldier, I find it hard to believe that the Soviet High Command was not putting powerful pressure on their political leaders to allow them to strike at Pakistan. After all, the Americans had expanded the Vietnam war into Laos and Cambodia, which had been used as secure bases by the Viet Cong. The Soviet Union, however, held back from any serious escalation. I had to ensure that we did not provoke them sufficiently to do so. A war with the Soviets would have been the end of Pakistan and could have unleashed a world war. It was a great responsibility, and one which I had to keep constantly in mind during those years.

An interesting example of the sort of incident that could quickly get out of hand, or lead to international confrontation, involved Soviet prisoners of war, and occurred about a year after I arrived at ISI. At that time a few Soviet prisoners were kept by the Parties in their unofficial jails on the outskirts of Peshawar. On this occasion Rabbani had thirty-five such captives, together with several suspect KHAD agents, locked up near his warehouse. Three of these Soviets had been taken prisoner two years earlier, and outwardly at least appeared to have accepted Islam—possibly as a way of saving their lives. Because of this they were not secured or watched vigilantly. One evening, when everyone was at prayers, they overpowered a solitary sentry, took his weapon, and then smashed the armoury door to get more. After clambering on to the roof they demanded to be handed over to the Soviet embassy.

Their captors did not agree. A long night was spent with the Soviets on the roof surrounded by well-armed Mujahideen. In the morning Rabbani’s military representative tried to reason with them, but as he was doing so the Soviets spotted some men trying to get closer by a covered approach. The escapees opened up with a 60mm mortar, killing one Mujahid and wounding others. The battle was joined. Then, without thinking, one Mujahid fired an RPG-7 into the building, straight into the ammunition store. The explosion shook Peshawar, sending missiles and rockets flying in all directions and shredding the Soviets and KHAD agents. Fortunately, although the firework display closed the Peshawar-Kohat road, no civilians were injured. The Soviet press got wind of what had happened and later described the incident as an heroic last stand against impossible odds, with the prisoners killing scores of the enemy before being overwhelmed. Our government was highly embarrassed, as they always emphatically denied holding Soviet prisoners in Pakistan. We received explicit orders that all such prisoners must be held in Afghanistan. We had learnt a lesson, at the cost of a valuable arms dump, and allowing the water to come perilously near the boil.

1983 had been a comparatively quiet year in the field as far as the Soviets were concerned. There were no Soviet divisional offensive sweeps similar to those launched the previous year around Herat and in the Panjsher Valley. Nevertheless, I was able to study a regimental-sized operation which gave me some inkling as to how the Soviets had adapted themselves tactically to a guerrilla war. It occurred six weeks after I joined ISI.

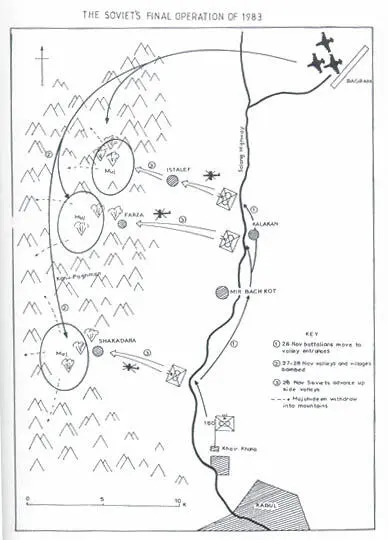

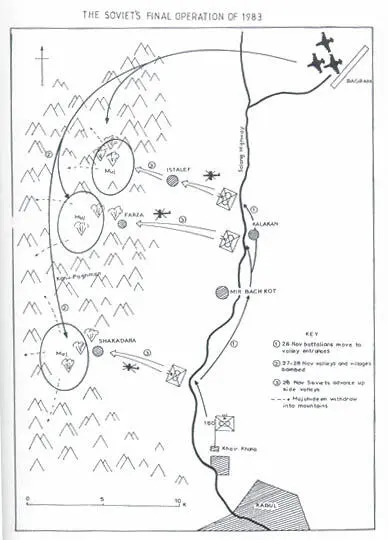

On 26 November long columns of armoured personnel carriers, tanks, trucks and guns drove north up the Salang Highway from Khair Khana camp on the outskirts of Kabul (see Map 4). They belonged to the 180th MRR of the Soviet 108th MRD. With them went Afghan Army units and helicopter gunships. The Soviet high command had been stung by the endless attacks on convoys using this critical life-line from the north. To the west of this road the massif, called the Koh-i-Paghman, rose up in places to over 12,000 feet. It was cut by several narrow east-west valleys that provided the Mujahideen with perfect covered approaches to and from the highway, from their bases in the mountains. Each valley had its tiny villages, with a larger one at the entrance, from which movement up and down the main road could be readily observed. The Soviets resolved to have a final attempt to clear three of these valleys before winter set in. From the equipment and weapons carried they appeared to have learned some expensive lessons.

Always edgy, always sensitive to sniper fire and ambushes at close range in the defiles, many troops now wore bulky metal-plate flak jackets. Special anti-sniper squads had been created to pinpoint marksmen. The firepower of the platoon had been boosted by the issue of the new AK-74 rifle, some with a single-shot 40mm grenade-launcher attached under the barrel, 30mm automatic grenade launchers with a range out to 800 metres and a high proportion of RPGs. Some platoons were being equipped with a highly demoralizing incendiary weapon. It resembled a bazooka and fired a shell up to 200 metres which exploded into a fireball on hitting the target. The standard APC of the MRD was the BTR-60 which mounted a 14.5mm heavy machine gun, a fine weapon provided the gunner could bring it to bear on his target. Often he could not, as his enemy had the disconcerting habit of overlooking him from high up steep slopes. Try as he might, the gunner could not elevate his gun sufficiently to engage. A 30° maximum elevation was perfect for the flat plains or undulating hills of Europe, but useless in the defiles of Afghanistan. By 1983 a workable solution had been improvised. Twin 23mm AA guns were fixed to the rear of a heavy-duty truck to give the required high rate of accurate fire at any angle up to the almost vertical.

Читать дальше