Experiments performed on Homo sapiens indicate that like rats humans too can be manipulated, and that it is possible to create or annihilate even complex feelings such as love, anger, fear and depression by stimulating the right spots in the human brain. The US military has recently initiated experiments on implanting computer chips in people’s brains, hoping to use this method to treat soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. 4In Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, doctors have pioneered a novel treatment for patients suffering from acute depression. They implant electrodes into the patient’s brain, and wire the electrodes to a minuscule computer implanted into the patient’s breast. On receiving a command from the computer, the electrodes use weak electric currents to paralyse the brain area responsible for the depression. The treatment does not always succeed, but in some cases patients reported that the feeling of dark emptiness that tormented them throughout their lives disappeared as if by magic.

One patient complained that several months after the operation, he had a relapse, and was overcome by severe depression. Upon inspection, the doctors found the source of the problem: the computer’s battery had run out of power. Once they changed the battery, the depression quickly melted away. 5

Due to obvious ethical restrictions, researchers implant electrodes into human brains only under special circumstances. Hence most relevant experiments on humans are conducted using non-intrusive helmet-like devices (technically known as ‘transcranial direct current stimulators’). The helmet is fitted with electrodes that attach to the scalp from outside. It produces weak electromagnetic fields and directs them towards specific brain areas, thereby stimulating or inhibiting select brain activities.

The American military experiments with such helmets in the hope of sharpening the focus and enhancing the performance of soldiers both in training sessions and on the battlefield. The main experiments are conducted in the Human Effectiveness Directorate, which is located in an Ohio air force base. Though the results are far from conclusive, and though the hype around transcranial stimulators currently runs far ahead of actual achievements, several studies have indicated that the method may indeed enhance the cognitive abilities of drone operators, air-traffic controllers, snipers and other personnel whose duties require them to remain highly attentive for extended periods. 6

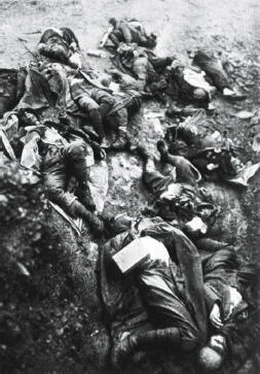

Sally Adee, a journalist for the New Scientist , was allowed to visit a training facility for snipers and test the effects herself. At first, she entered a battlefield simulator without wearing the transcranial helmet. Sally describes how fear swept over her as she saw twenty masked men, strapped with suicide bombs and armed with rifles, charge straight towards her. ‘For every one I manage to shoot dead,’ writes Sally, ‘three new assailants pop up from nowhere. I’m clearly not shooting fast enough, and panic and incompetence are making me continually jam my rifle.’ Luckily for her, the assailants were just video images, projected on huge screens all around her. Still, she was so disappointed with her poor performance that she felt like putting down the rifle and leaving the simulator.

Then they wired her up to the helmet. She reports feeling nothing unusual, except a slight tingle and a strange metallic taste in her mouth. Yet she began picking off the terrorists one by one, as coolly and methodically as if she were Rambo or Clint Eastwood. ‘As twenty of them run at me brandishing their guns, I calmly line up my rifle, take a moment to breathe deeply, and pick off the closest one, before tranquilly assessing my next target. In what seems like next to no time, I hear a voice call out, “Okay, that’s it.” The lights come up in the simulation room ... In the sudden quiet amid the bodies around me, I was really expecting more assailants, and I’m a bit disappointed when the team begins to remove my electrodes. I look up and wonder if someone wound the clocks forward. Inexplicably, twenty minutes have just passed. “How many did I get?” I ask the assistant. She looks at me quizzically. “All of them.”’

The experiment changed Sally’s life. In the following days she realised she has been through a ‘near-spiritual experience ... what defined the experience was not feeling smarter or learning faster: the thing that made the earth drop out from under my feet was that for the first time in my life, everything in my head finally shut up ... My brain without self-doubt was a revelation. There was suddenly this incredible silence in my head ... I hope you can sympathise with me when I tell you that the thing I wanted most acutely for the weeks following my experience was to go back and strap on those electrodes. I also started to have a lot of questions. Who was I apart from the angry bitter gnomes that populate my mind and drive me to failure because I’m too scared to try? And where did those voices come from?’ 7

Some of those voices repeat society’s prejudices, some echo our personal history, and some articulate our genetic legacy. All of them together, says Sally, create an invisible story that shapes our conscious decisions in ways we seldom grasp. What would happen if we could rewrite our inner monologues, or even silence them completely on occasion? 8

As of 2016, transcranial stimulators are still in their infancy, and it is unclear if and when they will become a mature technology. So far they provide enhanced capabilities for only short durations, and even Sally Adee’s twenty-minute experience may be quite exceptional (or perhaps even the outcome of the notorious placebo effect). Most published studies of transcranial stimulators are based on very small samples of people operating under special circumstances, and the long-term effects and hazards are completely unknown. However, if the technology does mature, or if some other method is found to manipulate the brain’s electric patterns, what would it do to human societies and to human beings?

People may well manipulate their brain’s electric circuits not just in order to shoot terrorists, but also to achieve more mundane liberal goals. Namely, to study and work more efficiently, immerse ourselves in games and hobbies, and be able to focus on what interests us at any particular moment, be it maths or football. However, if and when such manipulations become routine, the supposedly free will of customers will become just another product we can buy. You want to master the piano but whenever practice time comes you actually prefer to watch television? No problem: just put on the helmet, install the right software, and you will be downright aching to play the piano.

You may counter-argue that the ability to silence or enhance the voices in your head will actually strengthen rather than undermine your free will. Presently, you often fail to realise your most cherished and authentic desires due to external distractions. With the help of the attention helmet and similar devices, you could more easily silence the alien voices of priests, spin doctors, advertisers and neighbours, and focus on what you want. However, as we will shortly see, the notion that you have a single self and that you could therefore distinguish your authentic desires from alien voices is just another liberal myth, debunked by the latest scientific research.

Who Are I?

Science undermines not only the liberal belief in free will, but also the belief in individualism. Liberals believe that we have a single and indivisible self. To be an individual means that I am in-dividual. Yes, my body is made up of approximately 37 trillion cells, 9and each day both my body and my mind go through countless permutations and transformations. Yet if I really pay attention and strive to get in touch with myself, I am bound to discover deep inside a single clear and authentic voice, which is my true self, and which is the source of all meaning and authority in the universe. For liberalism to make sense, I must have one – and only one – true self, for if I had more than one authentic voice, how would I know which voice to heed in the polling station, in the supermarket and in the marriage market?

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу