On the other hand, technology often defines the scope and limits of our religious visions, like a waiter that demarcates our appetites by handing us a menu. New technologies kill old gods and give birth to new gods. That’s why agricultural deities were different from hunter-gatherer spirits, why factory hands fantasise about different paradises than peasants and why the revolutionary technologies of the twenty-first century are far more likely to spawn unprecedented religious movements than to revive medieval creeds. Islamic fundamentalists may repeat the mantra that ‘Islam is the answer’, but religions that lose touch with the technological realities of the day lose their ability even to understand the questions being asked. What will happen to the job market once artificial intelligence outperforms humans in most cognitive tasks? What will be the political impact of a massive new class of economically useless people? What will happen to relationships, families and pension funds when nanotechnology and regenerative medicine turn eighty into the new fifty? What will happen to human society when biotechnology enables us to have designer babies, and to open unprecedented gaps between rich and poor?

You will not find the answers to any of these questions in the Qur’an or sharia law, nor in the Bible or in the Confucian Analects , because nobody in the medieval Middle East or in ancient China knew much about computers, genetics or nanotechnology. Radical Islam may promise an anchor of certainty in a world of technological and economic storms – but in order to navigate a storm, you need a map and a rudder rather than just an anchor. Hence radical Islam may appeal to people born and raised in its fold, but it has precious little to offer unemployed Spanish youths or anxious Chinese billionaires.

True, hundreds of millions may nevertheless go on believing in Islam, Christianity or Hinduism. But numbers alone don’t count for much in history. History is often shaped by small groups of forward-looking innovators rather than by the backward-looking masses. Ten thousand years ago most people were hunter-gatherers and only a few pioneers in the Middle East were farmers. Yet the future belonged to the farmers. In 1850 more than 90 per cent of humans were peasants, and in the small villages along the Ganges, the Nile and the Yangtze nobody knew anything about steam engines, railroads or telegraph lines. Yet the fate of these peasants had already been sealed in Manchester and Birmingham by the handful of engineers, politicians and financiers who spearheaded the Industrial Revolution. Steam engines, railroads and telegraphs transformed the production of food, textiles, vehicles and weapons, giving industrial powers a decisive edge over traditional agricultural societies.

Even when the Industrial Revolution spread around the world and penetrated up the Ganges, Nile and Yangtze, most people continued to believe in the Vedas, the Bible, the Qur’an and the Analects more than in the steam engine. As today, so too in the nineteenth century there was no shortage of priests, mystics and gurus who argued that they alone hold the solution to all of humanity’s woes, including to the new problems created by the Industrial Revolution. For example, between the 1820s and 1880s Egypt (backed by Britain) conquered Sudan, and tried to modernise the country and incorporate it into the new international trade network. This destabilised traditional Sudanese society, creating widespread resentment and fostering revolts. In 1881 a local religious leader, Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdallah, declared that he was the Mahdi (the Messiah), sent to establish the law of God on earth. His supporters defeated the Anglo-Egyptian army, and beheaded its commander – General Charles Gordon – in a gesture that shocked Victorian Britain. They then established in Sudan an Islamic theocracy governed by sharia law, which lasted until 1898.

Meanwhile in India, Dayananda Saraswati headed a Hindu revival movement, whose basic principle was that the Vedic scriptures are never wrong. In 1875 he founded the Arya Samaj (Noble Society), dedicated to the spreading of Vedic knowledge – though truth be told, Dayananda often interpreted the Vedas in a surprisingly liberal way, supporting for example equal rights for women long before the idea became popular in the West.

Dayananda’s contemporary, Pope Pius IX, had much more conservative views about women, but shared Dayananda’s admiration for superhuman authority. Pius led a series of reforms in Catholic dogma, and established the novel principle of papal infallibility, according to which the Pope can never err in matters of faith (this seemingly medieval idea became binding Catholic dogma only in 1870, eleven years after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species ).

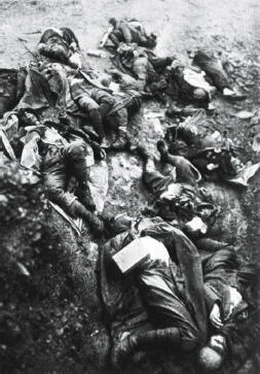

Thirty years before the Pope discovered that he is incapable of making mistakes, a failed Chinese scholar called Hong Xiuquan had a succession of religious visions. In these visions, God revealed that Hong was none other than the younger brother of Jesus Christ. God then invested Hong with a divine mission. He told Hong to expel the Manchu ‘demons’ that had ruled China since the seventeenth century, and establish on earth the Great Peaceful Kingdom of Heaven (Taiping Tiānguó). Hong’s message fired the imagination of millions of desperate Chinese, who were shaken by China’s defeats in the Opium Wars and by the coming of modern industry and European imperialism. But Hong did not lead them to a kingdom of peace. Rather, he led them against the Manchu Qing dynasty in the Taiping Rebellion – the deadliest war of the nineteenth century. From 1850 to 1864, at least 20 million people lost their lives; far more than in the Napoleonic Wars or in the American Civil War.

Hundreds of millions clung to the religious dogmas of Hong, Dayananda, Pius and the Mahdi even as industrial factories, railroads and steamships filled the world. Yet most of us don’t think about the nineteenth century as the age of faith. When we think of nineteenth-century visionaries, we are far more likely to recall Marx, Engels and Lenin than the Mahdi, Pius IX or Hong Xiuquan. And rightly so. Though in 1850 socialism was only a fringe movement, it soon gathered momentum, and changed the world in far more profound ways than the self-proclaimed messiahs of China and Sudan. If you count on national health services, pension funds and free schools, you need to thank Marx and Lenin (and Otto von Bismarck) far more than Hong Xiuquan or the Mahdi.

Why did Marx and Lenin succeed where Hong and the Mahdi failed? Not because socialist humanism was philosophically more sophisticated than Islamic and Christian theology, but rather because Marx and Lenin devoted more attention to understanding the technological and economic realities of their time than to perusing ancient texts and prophetic dreams. Steam engines, railroads, telegraphs and electricity created unheard-of problems as well as unprecedented opportunities. The experiences, needs and hopes of the new class of urban proletariats were simply too different from those of biblical peasants. To answer these needs and hopes, Marx and Lenin studied how a steam engine functions, how a coal mine operates, how railroads shape the economy and how electricity influences politics.

Lenin was once asked to define communism in a single sentence. ‘Communism is power to worker councils,’ he said, ‘plus electrification of the whole country.’ There can be no communism without electricity, without railroads, without radio. You couldn’t establish a communist regime in sixteenth-century Russia, because communism necessitates the concentration of information and resources in one hub. ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’ only works when produce can easily be collected and distributed across vast distances, and when activities can be monitored and coordinated over entire countries.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу