Professor Andersson can go to sleep at night with a clean conscience. The fact that customers are buying his enhanced animal products implies that he is meeting their needs and desires and is therefore doing good. By the same logic, if some multinational corporation wants to know whether it lives up to its ‘Don’t be evil’ motto, it need only take a look at its bottom line. If it makes loads of money, it means that millions of people like its products, which implies that it is a force for good. If someone objects and says that people might make the wrong choice, he will be quickly reminded that the customer is always right, and that human feelings are the source of all meaning and authority. If millions of people freely choose to buy the company’s products, who are you to tell them that they are wrong?

Finally, the rise of humanist ideas has revolutionised the educational system too. In the Middle Ages the source of all meaning and authority was external, hence education focused on instilling obedience, memorising scriptures and studying ancient traditions. Teachers presented pupils with a question, and the pupils had to remember how Aristotle, King Solomon or St Thomas Aquinas answered it.

Humanism in Five Images

Humanist Politics: the voter knows best.

© Sadik Gulec/Shutterstock.com.

Humanist Economics: the customer is always right.

© CAMERIQUE/ClassicStock/Corbis.

Humanist Aesthetics: beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. (Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain in a special exhibition of modern art at the National Gallery of Scotland.)

© Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images.

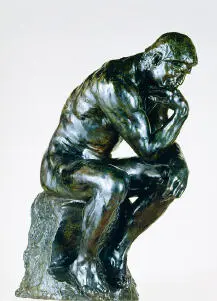

Humanist Ethics: if it feels good – do it!

© Molly Landreth/Getty Images.

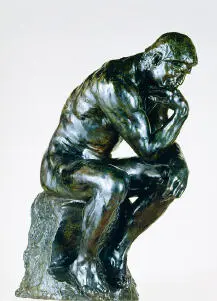

Humanist Education: think for yourself!

The Thinker , 1880–81 (bronze), Rodin, Auguste, Burrell Collection, Glasgow © Culture and Sport Glasgow (Museums)/Bridgeman Images.

In contrast, modern humanist education believes in teaching students to think for themselves. It is good to know what Aristotle, Solomon and Aquinas thought about politics, art and economics; yet since the supreme source of meaning and authority lies within ourselves, it is far more important to know what you think about these matters. Ask a teacher – whether in kindergarten, school or college – what she is trying to teach. ‘Well,’ she will answer, ‘I teach the kids history, or quantum physics, or art – but above all I try to teach them to think for themselves.’ It may not always succeed, but that is what humanist education seeks to do.

As the source of meaning and authority was relocated from the sky to human feelings, the nature of the entire cosmos changed. The exterior universe – hitherto teeming with gods, muses, fairies and ghouls – became empty space. The interior world – hitherto an insignificant enclave of crude passions – became deep and rich beyond measure. Angels and demons were transformed from real entities roaming the forests and deserts of the world into inner forces within our own psyche. Heaven and hell too ceased to be real places somewhere above the clouds and below the volcanoes, and were instead interpreted as internal mental states. You experience hell every time you ignite the fires of anger and hatred within your heart; and you enjoy heavenly bliss every time you forgive your enemies, repent your own misdeeds and share your wealth with the poor.

When Nietzsche declared that God is dead, this is what he meant. At least in the West, God has become an abstract idea that some accept and others reject, but it makes little difference either way. In the Middle Ages, without a god I had no source of political, moral and aesthetic authority. I could not tell what was right, good or beautiful. Who could live like that? Today, in contrast, it is very easy not to believe in God, because I pay no price for my unbelief. I can be a complete atheist, and still draw a very rich mix of political, moral and aesthetical values from my inner experience.

If I believe in God at all, it is my choice to believe. If my inner self tells me to believe in God – then I believe. I believe because I feel God’s presence, and my heart tells me He is there. But if I no longer feel God’s presence, and if my heart suddenly tells me that there is no God – I will cease believing. Either way, the real source of authority is my own feelings. So even while saying that I believe in God, the truth is I have a much stronger belief in my own inner voice.

Follow the Yellow Brick Road

Like every other source of authority, feelings have their shortcomings. Humanism assumes that each human has a single authentic inner self, but when I try to listen to it, I often encounter either silence or a cacophony of contending voices. In order to overcome this problem, humanism has upheld not just a new source of authority, but also a new method for getting in touch with authority and gaining true knowledge.

In medieval Europe, the chief formula for knowledge was: Knowledge = Scriptures × Logic. *If we want to know the answer to some important question, we should read scriptures, and use our logic to understand the exact meaning of the text. For example, scholars who wished to know the shape of the earth scanned the Bible looking for relevant references. One pointed out that in Job 38:13, it says that God can ‘take hold of the edges of the earth, and the wicked be shaken out of it’. This implies – reasoned the pundit – that because the earth has ‘edges’ of which we can ‘take hold’, it must be a flat square. Another sage rejected this interpretation, calling attention to Isaiah 40:22, where it says that God ‘sits enthroned above the circle of the earth’. Isn’t that proof that the earth is round? In practice, that meant that scholars sought knowledge by spending years in schools and libraries, reading more and more texts, and sharpening their logic so they could understand the texts correctly.

The Scientific Revolution proposed a very different formula for knowledge: Knowledge = Empirical Data × Mathematics. If we want to know the answer to some question, we need to gather relevant empirical data, and then use mathematical tools to analyse the data. For example, in order to gauge the true shape of the earth, we can observe the sun, the moon and the planets from various locations across the world. Once we have amassed enough observations, we can use trigonometry to deduce not only the shape of the earth, but also the structure of the entire solar system. In practice, that means that scientists seek knowledge by spending years in observatories, laboratories and research expeditions, gathering more and more empirical data, and sharpening their mathematical tools so they could interpret the data correctly.

The scientific formula for knowledge led to astounding breakthroughs in astronomy, physics, medicine and countless other disciplines. But it had one huge drawback: it could not deal with questions of value and meaning. Medieval pundits could determine with absolute certainty that it is wrong to murder and steal, and that the purpose of human life is to do God’s bidding, because scriptures said so. Scientists could not come up with such ethical judgements. No amount of data and no mathematical wizardry can prove that it is wrong to murder. Yet human societies cannot survive without such value judgements.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу