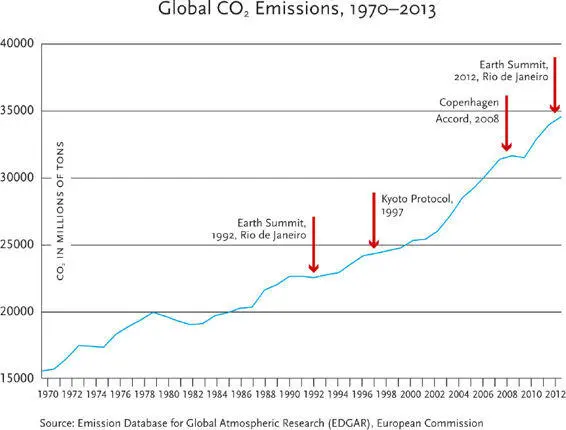

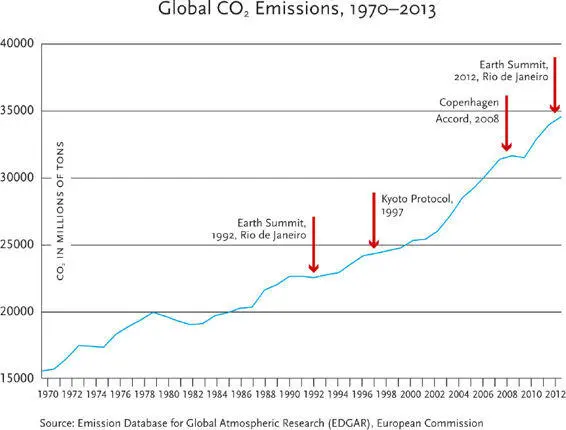

All the talk about global warming, and all the conferences, summits and protocols, have so far failed to curb global greenhouse emissions. If you look closely at the graph you see that emissions go down only during periods of economic crises and stagnation. Thus the small downturn in greenhouse emissions in 2008–9 was due not to the signing of the Copenhagen Accord, but to the global financial crisis.

Source: Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR), European Commission.

In December 2015 more ambitious targets were set in the Paris Agreement, which calls for limiting average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. But many of the painful steps necessary to reach this aim have conveniently been postponed to after 2030, or even to the second half of the twenty-first century, effectively passing the hot potato to the next generation. Current administrations would be able to reap immediate political benefits from looking green, while the heavy political price of reducing emissions (and slowing growth) is bequeathed to future administrations. Even so, at the time of writing (January 2016) it is far from certain that the USA and other leading polluters will ratify the Paris Agreement. Too many politicians and voters believe that as long as the economy grows, scientists and engineers could always save us from doomsday. When it comes to climate change, many growth true-believers do not just hope for miracles – they take it for granted that the miracles will happen.

How rational is it to risk the future of humankind on the assumption that future scientists will make some unknown discoveries? Most of the presidents, ministers and CEOs who run the world are very rational people. Why are they willing to take such a gamble? Maybe because they don’t think they are gambling on their own personal future. Even if bad comes to worse and science cannot hold off the deluge, engineers could still build a hi-tech Noah’s Ark for the upper caste, while leaving billions of others to drown. The belief in this hi-tech Ark is currently one of the biggest threats to the future of humankind and of the entire ecosystem. People who believe in the hi-tech Ark should not be put in charge of the global ecology, for the same reason that people who believe in a heavenly afterlife should not be given nuclear weapons.

And what about the poor? Why aren’t they protesting? If and when the deluge comes, they will bear the full cost of it. However, they will also be the first to bear the cost of economic stagnation. In a capitalist world, the lives of the poor improve only when the economy grows. Hence they are unlikely to support any steps to reduce future ecological threats that are based on slowing down present-day economic growth. Protecting the environment is a very nice idea, but those who cannot pay their rent are worried about their overdraft far more than about melting ice caps.

The Rat Race

Even if we go on running fast enough and manage to fend off both economic collapse and ecological meltdown, the race itself creates huge problems. On the individual level, it results in high levels of stress and tension. After centuries of economic growth and scientific progress, life should have become calm and peaceful, at least in the most advanced countries. If our ancestors knew what tools and resources stand ready at our command, they would have surmised we must be enjoying celestial tranquillity, free of all cares and worries. The truth is very different. Despite all our achievements, we feel a constant pressure to do and produce even more.

We blame ourselves, our boss, the mortgage, the government, the school system. But it’s not really their fault. It’s the modern deal, which we have all signed up to on the day we were born. In the premodern world, people were akin to lowly clerks in a socialist bureaucracy. They punched their card, and then waited for somebody else to do something. In the modern world, we humans run the business. So we are under constant pressure day and night.

On the collective level, the race manifests itself in ceaseless upheavals. Whereas previously social and political systems endured for centuries, today every generation destroys the old world and builds a new one in its place. As the Communist Manifesto brilliantly put it, the modern world positively requires uncertainty and disturbance. All fixed relations and ancient prejudices are swept away, and new structures become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air. It isn’t easy to live in such a chaotic world, and it is even harder to govern it.

Hence modernity needs to work hard to ensure that neither human individuals nor the human collective will try to retire from the race, despite all the tension and chaos it creates. For that purpose, modernity upholds growth as a supreme value for whose sake we should make every sacrifice and risk every danger. On the collective level, governments, firms and organisations are encouraged to measure their success in terms of growth, and to fear equilibrium as if it were the Devil. On the individual level, we are inspired to constantly increase our income and our standard of living. Even if you are quite satisfied with your current conditions, you should strive for more. Yesterday’s luxuries become today’s necessities. If once you could live well in a three-bedroom apartment with one car and a single desktop, today you need a five-bedroom house with two cars and a host of iPods, tablets and smartphones.

It wasn’t very hard to convince individuals to want more. Greed comes easily to humans. The big problem was to convince collective institutions such as states and churches to go along with the new ideal. For millennia, societies strove to curb individual desires and bring them into some kind of balance. It was well known that people wanted more and more for themselves, but when the pie was of a fixed size, social harmony depended on restraint. Avarice was bad. Modernity turned the world upside down. It convinced human collectives that equilibrium is far more frightening than chaos, and because avarice fuels growth, it is a force for good. Modernity accordingly inspired people to want more, and dismantled the age-old disciplines that curbed greed.

The resulting anxieties were assuaged to a large extent by free-market capitalism, which is one reason why this particular ideology has become so popular. Capitalist thinkers repeatedly calm us: ‘Don’t worry, it will be okay. Provided the economy grows, the invisible hand of the market will take care of everything else.’ Capitalism has thus sanctified a voracious and chaotic system that grows by leaps and bounds, without anyone understanding what is happening and where we are rushing. (Communism, which also believed in growth, thought it could prevent chaos and orchestrate growth through state planning. After initial successes, it eventually fell far behind the messy free-market cavalcade.)

Bashing free-market capitalism is high on the intellectual agenda nowadays. Since capitalism dominates our world, we should indeed make every effort to understand its shortcomings, before they cause apocalyptic catastrophes. Yet criticising capitalism should not blind us to its advantages and attainments. So far, it’s been an amazing success – at least if you ignore the potential for future ecological meltdown, and if you measure success by the yardstick of production and growth. In 2016 we may be living in a stressful and chaotic world, but the doomsday prophecies of collapse and violence have not materialised, whereas the scandalous promises of perpetual growth and global cooperation are fulfilled. Although we experience occasional economic crises and international wars, in the long run capitalism has not only managed to prevail, but also to overcome famine, plague and war. For thousands of years priests, rabbis and muftis explained that humans cannot overcome famine, plague and war by their own efforts. Then along came the bankers, investors and industrialists, and within 200 years managed to do exactly that.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу