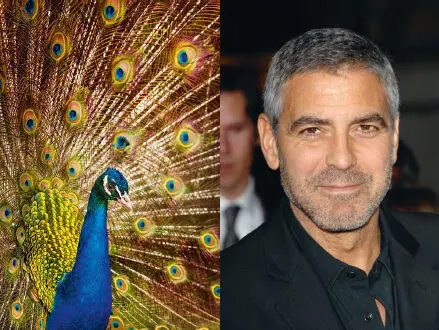

A peacock and a man. When you look at these images, data on proportions, colours and sizes gets processed by your biochemical algorithms, causing you to feel attraction, repulsion or indifference.

Left: © Bergserg/Shutterstock.com. Right: © s_bukley/Shutterstock.com.

It took scientists many years to acknowledge this. Not long ago psychologists doubted the importance of the emotional bond between parents and children even among humans. In the first half of the twentieth century, and despite the influence of Freudian theories, the dominant behaviourist school argued that relations between parents and children were shaped by material feedback; that children needed mainly food, shelter and medical care; and that children bonded with their parents simply because the latter provide these material needs. Children who demanded warmth, hugs and kisses were thought to be ‘spoiled’. Childcare experts warned that children who were hugged and kissed by their parents would grow up to be needy, egotistical and insecure adults. 21

John Watson, a leading childcare authority in the 1920s, sternly advised parents, ‘Never hug and kiss [your children], never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say goodnight. Shake hands with them in the morning.’ 22The popular magazine Infant Care explained that the secret of raising children is to maintain discipline and to provide the children’s material needs according to a strict daily schedule. A 1929 article instructed parents that if an infant cries out for food before the normal feeding time, ‘Do not hold him, nor rock him to stop his crying, and do not nurse him until the exact hour for the feeding comes. It will not hurt the baby, even the tiny baby, to cry.’ 23

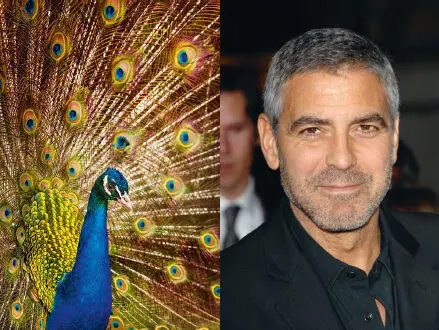

Only in the 1950s and 1960s did a growing consensus of experts abandon these strict behaviourist theories and acknowledge the central importance of emotional needs. In a series of famous (and shockingly cruel) experiments, the psychologist Harry Harlow separated infant monkeys from their mothers shortly after birth, and isolated them in small cages. When given a choice between a metal dummy-mother fitted with a milk bottle, and a soft cloth-covered dummy with no milk, the baby monkeys clung to the barren cloth mother for all they were worth.

Those baby monkeys knew something that John Watson and the experts of Infant Care failed to realise: mammals can’t live on food alone. They need emotional bonds too. Millions of years of evolution preprogrammed the monkeys with an overwhelming desire for emotional bonding. Evolution also imprinted them with the assumption that emotional bonds are more likely to be formed with soft furry things than with hard and metallic objects. (This is also why small human children are far more likely to become attached to dolls, blankets and smelly rags than to cutlery, stones or wooden blocks.) The need for emotional bonds is so strong that Harlow’s baby monkeys abandoned the nourishing metal dummy and turned their attention to the only object that seemed capable of answering that need. Alas, the cloth-mother never responded to their affection and the little monkeys consequently suffered from severe psychological and social problems, and grew up to be neurotic and asocial adults.

Today we look back with incomprehension at early twentieth-century child-rearing advice. How could experts fail to appreciate that children have emotional needs, and that their mental and physical health depends as much on providing for these needs as on food, shelter and medicines? Yet when it comes to other mammals we keep denying the obvious. Like John Watson and the Infant Care experts, farmers throughout history took care of the material needs of piglets, calves and kids, but tended to ignore their emotional needs. Thus both the meat and dairy industries are based on breaking the most fundamental emotional bond in the mammal kingdom. Farmers get their breeding sows and dairy cows impregnated again and again. Yet the piglets and calves are separated from their mothers shortly after birth, and often pass their days without ever sucking at her teats or feeling the warm touch of her tongue and body. What Harry Harlow did to a few hundred monkeys, the meat and dairy industries are doing to billions of animals every year. 24

The Agricultural Deal

How did farmers justify their behaviour? Whereas hunter-gatherers were seldom aware of the damage they inflicted on the ecosystem, farmers knew perfectly well what they were doing. They knew they were exploiting domesticated animals and subjugating them to human desires and whims. They justified their actions in the name of new theist religions, which mushroomed and spread in the wake of the Agricultural Revolution. Theist religions maintained that the universe is ruled by a group of great gods – or perhaps by a single capital ‘G’ God. We don’t normally associate this idea with agriculture, but at least in their beginnings theist religions were an agricultural enterprise. The theology, mythology and liturgy of religions such as Judaism, Hinduism and Christianity revolved at first around the relationship between humans, domesticated plants and farm animals. 25

Biblical Judaism, for instance, catered to peasants and shepherds. Most of its commandments dealt with farming and village life, and its major holidays were harvest festivals. People today imagine the ancient temple in Jerusalem as a kind of big synagogue where priests clad in snow-white robes welcomed devout pilgrims, melodious choirs sang psalms and incense perfumed the air. In reality, it looked much more like a cross between a slaughterhouse and a barbecue joint than a modern synagogue. The pilgrims did not come empty-handed. They brought with them a never-ending stream of sheep, goats, chickens and other animals, which were sacrificed at the god’s altar and then cooked and eaten. The psalm-singing choirs could hardly be heard over the bellowing and bleating of calves and kids. Priests in bloodstained outfits cut the victims’ throats, collected the gushing blood in jars and spilled it over the altar. The perfume of incense mixed with the odours of congealed blood and roasted meat, while swarms of black flies buzzed just about everywhere (see, for example, Numbers 28, Deuteronomy 12, and 1 Samuel 2). A modern Jewish family that celebrates a holiday by having a barbecue on their front lawn is much closer to the spirit of biblical times than an orthodox family that spends the time studying scriptures in a synagogue.

Theist religions, such as biblical Judaism, justified the agricultural economy through new cosmological myths. Animist religions had previously depicted the universe as a grand Chinese opera with a limitless cast of colourful actors. Elephants and oak trees, crocodiles and rivers, mountains and frogs, ghosts and fairies, angels and demons – each had a role in the cosmic opera. Theist religions rewrote the script, turning the universe into a bleak Ibsen drama with just two main characters: man and God. The angels and demons somehow survived the transition, becoming the messengers and servants of the great gods. Yet the rest of the animist cast – all the animals, plants and other natural phenomena – were transformed into silent decor. True, some animals were considered sacred to this or that god, and many gods had animal features: the Egyptian god Anubis had the head of a jackal, and even Jesus Christ was frequently depicted as a lamb. Yet ancient Egyptians could easily tell the difference between Anubis and an ordinary jackal sneaking into the village to hunt chickens, and no Christian butcher ever mistook the lamb under his knife for Jesus.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу