The characters of Gargantua, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza inhabit the collective imagination. They help form our attitudes to life. But as Harold Bloom, Professor of Humanities at Yale University and author of the key book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human , has shown, no single writer has populated our imagination with archetypes like Shakespeare: Falstaff, Hamlet, Ophelia, Lear, Prospero, Caliban, Bottom, Othello, Iago, Malvolio, Macbeth and his Lady, Romeo and Juliet. In fact, after Jesus Christ no other individual has done so much to develop and expand the human sense of an interior life. If Jesus Christ planted the seed of interior life, Shakespeare helped it to grow, populated it and gave us the sense we all have today that we each contain inside us an inner cosmos as expansive as the outer cosmos.

Great writers are the architects of our consciousness, in Rabelais, Cervantes and Shakespeare, above all in the soliloquies of Hamlet, we also see the seeds of the sense we have today of personal turning points, vital decisions to be made. Before the great writers of the Renaissance, any inkling of such things could only have come from sermons.

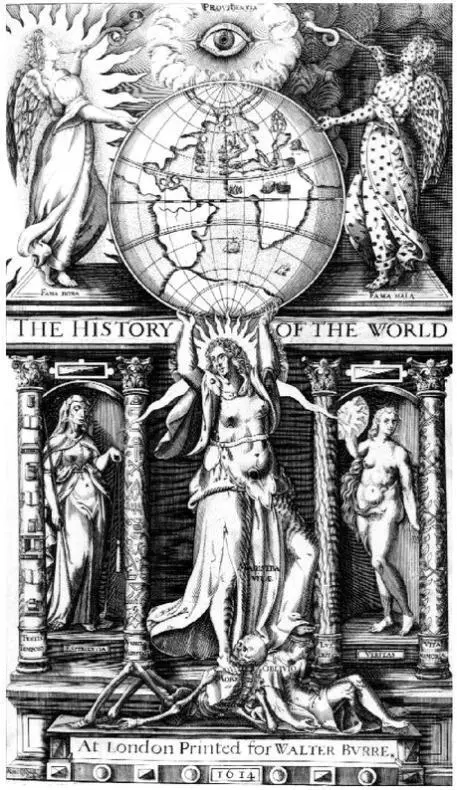

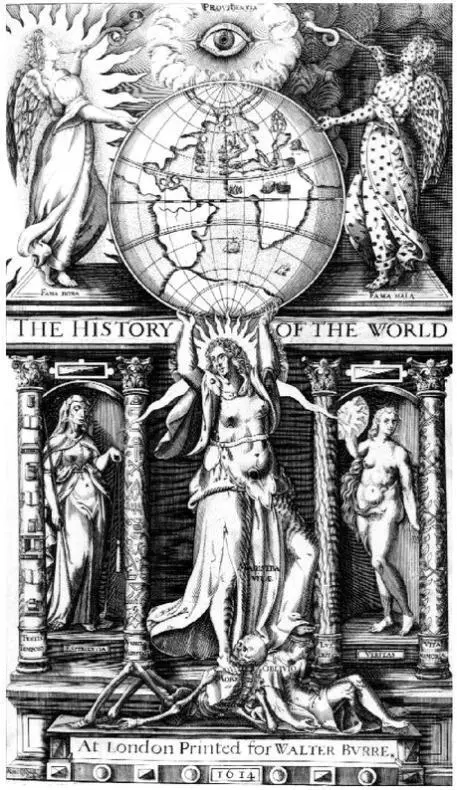

RIGHT The History of the World, 1614. Sir Walter Raleigh, the famous adventurer, was a member of a secret society called the School of Night. So shadowy was this society that some recent critics have even doubted its existence, but Raleigh undoubtedly shared esoteric ideas with Christopher Marlowe and George Chapman, author of The Shadow of Night. O ne of the secrets they kept was ‘atheism’. Raleigh feared the prolonged torture, disembowelling and slow death that had overtaken another friend, Thomas Kyd, for professing atheistic views. But none of them was an atheist in the modern sense of denying the reality of spirit worlds or denying that disembodied beings intervened in the material world in a supernatural way. In Faust Marlowe wrote one of the most learned, esoteric works of world literature dealing with the dangers of commerce with the spirit worlds.

There was a brilliant analysis of this frontispiece of his literary masterpiece by David Fideler in the much-missed Gnosis magazine. On one level, says Fideler, it was meant to illustrate Raleigh’s view of history as the unfolding of Divine Providence according to Cicero’s definition: ‘History bears witness to the passing of the ages, sheds light upon reality, gives life to recollection and guidance to human existence, and brings tidings of ancient days.’ On another level, he points out, this design embodies the cabalistic Tree of Life with planetary correspondences at the nodes. The figure on the left is Bon Fama, the Fama of the Rosicrucian Manifestoes.

There is a shadowy side to this new interior richness, which, again, we see most clearly in the soliloquies of Hamlet. The new sense of detachment that allows someone to withdraw from the senses and roam around his interior world is double-edged, carrying with it the danger of feeling alienated from the world. Hamlet languishes in just such a state of alienation when he is not sure whether it is better ‘to be or not to be’. This is a long way from the cry of Achilles, who wanted to live in the light of the sun at all costs.

As an initiate Shakespeare was helping to forge the new form of consciousness. But how do we know Shakespeare was an initiate?

In the Anglo-Saxon countries at least Shakespeare has done more than any other writer to form our idea of beings from the spirit worlds and the way they may sometimes break into the material world. We need only think of Ariel, Caliban, Puck, Oberon and Titania. Many thespians still believe that Macbeth contains dangerous occult formulae that give it the force of a magical ceremony when performed. Prospero in The Tempest is the archetype of the Magus, based on Elizabeth’s court astrologer Dr Dee. A spirit spoke to Dee on 24 March 1583, talking about the future course of nature and reason, saying, ‘New Worlds shall spring of these. New manners; strange Men.’ Compare this with ‘O wonder! How beauteous mankind is. O brave new world, that has such people in it.’

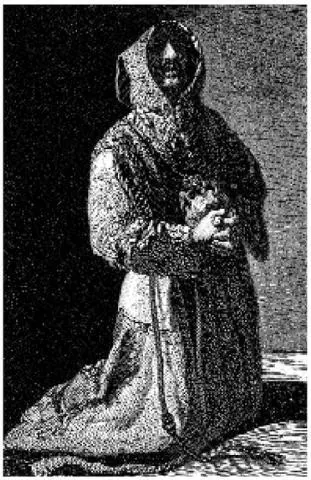

Initiatic images of meditating on a skull, often found in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries from Hamlet through the brooding monks of Zurbarán to the posing of Byron. These are not mere reminders that one day we must die. The skull meditation alludes to arcane techniques of invoking the spirits of dead ancestors — techniques inherited and nurtured by secret societies such as the Rosicrucians and the Jesuits.

When we enter the Green Wood of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the other comedies we are re-entering the ancient wood we walked through in Chapter 2. We are returning to an archaic form of consciousness in which all nature is animated by spirits. In all art and literature twisted vegetation usually signals we are entering the realm of the esoteric, the etheric dimension. Shakespeare’s writing is, of course, dense with flower imagery. Critics have often commented on the use of the rose as an occult, Rosicrucian symbol in The Faerie Queene , written by Edmund Spenser in 1589, but no writer in English has used the symbol of the rose more often — or more occultly — than Shakespeare. There are seven roses on the memorial to Shakespeare in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, and, as we shall see shortly, the seven roses are the Rosicrucian symbol of the chakras.

It is here that one of the distinctions created by modern, positivist philosophy may prove useful. According to logical positivism an apparent assertion is really asserting nothing if no evidence would disprove it. This argument is sometimes used to try to disprove the existence of God. If no conceivable turn of events would ever count against the existence of God, it is argued, then by asserting that God exists we are not really asserting anything.

In some religious orders, the novitiate lies in a coffin between four candles, the Miserere is sung and he then rises to be given a new name as a sign of rebirth. Painting by Francisco Zurbarán.

Looked at in this way the assertion ‘the historical personage Shakespeare wrote the plays that bear his name’ actually asserts very little. We know so little about the man that it has no bearing at all on our understanding of the plays. Shakespeare is an enigma. Like Jesus Christ he revolutionized human consciousness yet left almost invisible traces on the contemporary historical record.

In order finally to get to grips with this mystery and to understand better the literary Renaissance that overtook England at this time, we must examine the largely overlooked Sufi content in the plays of Shakespeare. Sufism, we saw, was the great source of the rose as a mystical symbol.

The basic plot of The Taming of the Shrew comes from the A Thousand and One Nights . The Arab title of A Thousand And One Nights , ALF LAYLA WA LAYLA, is a coded phrase meaning Mother of Records. This is an allusion to the tradition that there lies hidden underneath the paws of the Sphinx, or in a parallel dimension, a secret library or ‘Hall of Records’, a storehouse of ancient wisdom from before the Flood. The title A Thousand and One Nights means to tell us, therefore, that the secrets of human evolution are encoded within.

Читать дальше