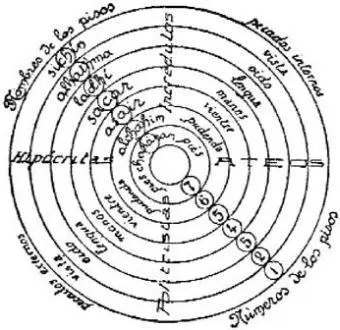

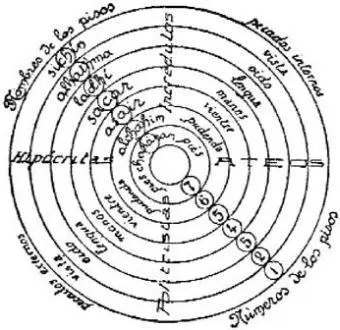

In the ancient world the underworld was conceived of as being seven-layered or seven-walled, as the labyrinth of Minos was depicted on Cretan coins. The same idea is to be found in Origen’s account of the Ophites with their invocations to the seven demons who guard the seven gates of the underworld. However, the closest model for Dante’s account of the underworld in the Commedia is now known to be the great Sufi master Ibn Arabi’s account of Mohammed’s journey into the other worlds in the Fotuhat. Illustration from early translation.

Like the Fotuhat and like an earlier model, the Egyptian Book of the Dead , the Commedia is, on one level, a guide to the afterlife, on another a manual of initiation and on a third level an account of the way that life in the material world — quite as much as the afterlife — is shaped by stars and planets.

The Commedia shows how when we behave badly in this life we are already constructing a Purgatory, a Hell, for ourselves in another dimension that intersects with our everyday lives. We are already suffering, tormented by demons. If we do not aspire to move up the spiral of the heavenly hierarchies, if we ‘make do’ with purely earthly successes and pleasures, we are already in Purgatory.

Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray has become a part of public consciousness. We all know that, beautiful and vain, Dorian keeps a painting in his attic, which decays and becomes monstrous as he plunges into a life of debauchery, while he himself remains perfect and unlined. At the end of the novel the decay in the painting suddenly afflicts Dorian all at once. According to Dante, we’re all Dorian Grays, creating monstrous selves and devising monstrous punishments for ourselves. What makes Dante’s vision incomparably grander than Wilde’s is that not only does he show that we each create a heaven and hell inside us, he also shows what our misdeeds do to the structure and very texture of the world. He turns the world inside out to reveal the hideous effects of our innermost thoughts and the deeds we most want kept secret. According to Dante, everything we do or think materially alters the universe. Umberto Eco has called his poem ‘the apotheosis of the virtual world’.

Giordano Bruno executed in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome. It’s often assumed that Bruno was burned at the stake by the church for championing the modern, scientific view that the earth revolves around the sun. In fact it was his esoteric views that really frightened the Church. His experiences of the spirit worlds led him to claim that there are an infinity of interlocking universes and dimensions. He invoked the authority of the ‘Pythagorean poet’, Virgil to back up his belief that the human spirit could travel between these universes, but would eventually ‘desire to return to the body’ in accordance with the laws of reincarnation.

IN 1439 A MYSTERIOUS STRANGER CALLED Gemistos Plethon slipped into the court of Cosimo de Medici, ruler of Florence. Plethon was carrying with him the lost Greek texts of Plato. As fate would have it, he was also carrying various neoplatonic texts, some Orphic hymns and, most intriguingly, some esoteric material which purported to date back to the Egypt of the pyramids.

Plethon came from Byzantium where an esoteric, neoplatonic tradition still thrived dating back to early Church fathers such as Clement and Origen — a tradition that Rome had repressed. Plethon was able to fire Cosimo with the idea of a lineage of universal but secret lore that went back beyond these early Christians to Plato, Orpheus, Hermes and the Chaldean Oracles. He whispered in Cosimo’s ear of a perennial philosophy of reincarnation and personal encounters with the gods of the hierarchies which might be achieved by ceremony and the ritual singing of the Hymns of Orpheus .

It is this appeal to vivid, personal experience that inspired the Renaissance. Cosimo de Medici employed the scholar Marsilio Ficino to translate Plethon’s documents, starting with Plato, but when Cosimo learned about the Egyptian material, he told Ficino to put Plato aside and translate the Egyptian stuff instead.

The spirit that Plethon introduced into Italy by his translations of the hermetica spread quickly among the cultural elite. Appetite for new experience, together with a fresh and vital relationship with the spirit worlds, is captured on the page by the Italian magus Giordano Bruno. He writes of a love that brings ‘excessive sweat, shrieks which deafen the stars, laments which reverberate in the caves of Hell, tortures which afflict the living spirit with stupor, sighs which make the gods swoon with compassion, and all this for those eyes, for that whiteness, those lips, that hair, that reserve, that little smile, that wryness, that eclipsed Sun, that disgust, that injury and distortion of nature, a shadow, a phantasm, dream, a Circean enchantment put to the service of generation…’

This is a new note in literature.

The literature of the Renaissance is lit up by the stars and planets. The great writers of Renaissance Italy invoked this energy by the active and intelligent use of the imagination. Like Helen Waddell, Frances Yates was not an esotericist — or, if she was, left no hint in her writings — but thanks to her meticulous research and brilliant analysis, and that of the scholars at the Warburg Institute who have followed in her footsteps, we have a detailed understanding of the esoteric discoveries of the Renaissance and of the ways they inspired art and literature. The translations of the hermetic texts by Marsilio Ficino talked of the fashioning of images in esoteric terms: ‘Our spirit, if it has been intent upon the work and upon the stars through imagination and emotion, is joined together with the very spirit of the world and with the rays of the stars through which the world-spirit acts.’ What Ficino is saying is that if you imagine as fully and vividly as you can the spirits of the planets and the stellar gods, then, as a result of this act of imagination, the power of the spirit may flow through you.

Raphael: Madonna and Child .

We saw in the last chapter that the Middle Ages was the great age of magic. Then esoteric thinkers and occultists began to construct images in their minds which gods and spirits could inhabit and make come alive, as once the makers of the temples and Mystery centres of the ancient world had manufactured objects such a statues for disembodied beings to use as bodies. In Italy in the Renaissance artists with esoteric beliefs began to recreate the magical images in their minds with paint and stone.

In the Middle Ages, the dissemination of grimoires had been a wholly underground, sub-cultural activity. Now the more widely published hermetic literature of the Renaissance gave instructions on how to construct talismans designed to draw down influences from the spirit worlds which were taken up by the artists of the day. Hermetic literature explained how occult influences could be more effective if they were constructed of metals appropriate to the spirit being invoked — gold for the god of the sun, for example, silver for the god of the moon. Particular colours, shapes, hieroglyphs and other sigils were revealed afresh as sympathetic to particular disembodied beings.

Читать дальше