IN THE CLOSING YEARS OF THE THIRTEENTH century a weak and sickly child was born. Shortly after birth he was taken in and looked after by twelve wise men. In Rudolf Steiner’s account, they lived in a building that had belonged to the Templars at Monsalvat on the border between France and Spain.

Because the boy was kept completely shut away from the outside world, the locals were unable to see anything of his miraculous nature. He was filled with such a strong, shining spirit that his little body became transparent.

The twelve men initiated him in about 1254, and he died shortly afterwards — having shared his spiritual vision with those who had looked after him. The thirteen had helped prepare for his next incarnation in which he would change the face of Europe.

ALBERTUS WAS BORN IN 1193, APPARENTLY a dull and stupid boy until, inspired by a vision of the Virgin Mary, he began to pursue his studies so zealously that he quickly became the most famous philosopher in Europe. He studied Aristotle’s science, physics, medicine, architecture, astrology and alchemy. The short text The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus , containing the central hermetic axiom ‘as above so below’, first surfaced into exoteric history as part of his library. He almost certainly explored methods of divining the presence of metals deep in the earth using occult means. It is said he built a strange automaton he called the Android, able to speak, perhaps even think and move about of its own free will. It was made of brass and other metals chosen because of their magical correspondences with heavenly bodies, and Albertus made it come alive by breathing magical incantations into it and with prayers.

The legend that Albertus Magnus was the architect of Cologne Cathedral probably derives from his authorship of Liber Constructionum Alberti , containing the secrets of Operative Freemasons, including the laying of the foundations of cathedrals along astronomical lines.

STORIES OF JOURNEYS UNDERGROUND, like those of Albertus Magnus, to discover metals, are often ways of alluding to underground initiations. We know that initiations of this type survived into the Middle Ages because of an account of one that took place in Ireland, which has come down to us from three sources.

A soldier called Owen, who served the English King Stephen, went to the Monastery of St Patrick in Donegal. Owen fasted for nine days, processing around the monastery and taking baths of ritual purification. On the ninth day he was admitted to the underground chamber ‘out of which all who enter do not return’. There he was laid down in a grave. The only light was from a single aperture. That night Owen was visited by fifteen men robed all in white, who warned him that he was about to undergo a trial. Then, all of a sudden, a troop of demons appeared. They held him over a fire, before showing him scenes of torment like those described by Virgil.

Finally, two elders came to guide him, and showed Owen a vision of Paradise.

ALBERTUS WAS SPIRITUAL GUIDE TO Thomas Aquinas, nearly thirty-three years his junior. It seems that Thomas smashed his master’s Android to pieces, in some accounts because he believed it diabolical — in others because it would never stop talking.

Aquinas had come to the University of Paris to study Aristotle at the feet of the master, but he was to discover that the greatest Aristotelean was in fact a Muslim. Averroës argued that Aristotelean logic showed Christianity to be absurd.

Would logic eat up religion, all true spirituality?

Aquinas’s life’s work culminated in his massive Summa Theologica , perhaps the most influential work of theology ever written. Its aim was to try to show that philosophy and Christianity are not only compatible — they illumine each other. Aquinas applied the sharpest analytical scalpel to thought about the spirit worlds. He was able to categorize the beings of the heavenly hierarchies, the great cosmic forces that create natural forms as well as creating our subjective experiences. The Summa contains, for example, the Church’s definitive teachings on the Four Elements and this is achieved with a living, penetrating intellect rather than a stultifying reshuffling of dead dogma.

Aquinas is a key figure in the secret history, then, because his great intellectual triumph over Averroës prevented Europe’s being overcome by scientific materialism several hundreds years too early.

Again it is important to bear in mind that this triumph was achieved from the standpoint of direct, personal experience of the spirit worlds. There is not a shadow of a doubt that Thomas Aquinas, like Albertus Magnus, was an alchemist, who believed it was possible to harness the power of disembodied spirits to effect changes in the material world. Of the many alchemical texts attributed to him, scholars accept at least one as undoubtedly genuine. In order to understand this better, it’s useful to compare him with his contemporary Roger Bacon.

Today alchemy can seem a strange, hole-in-the-wall activity. In fact it is quite familiar to all church-going Christians because it is what is said to take place at the climax of the Mass. Aquinas first formulated the doctrine of the transubstantiation of the bread and wine. What he described is essentially an alchemical process in which the substance of the bread and wine changes and a parallel transubstantiation takes place in the human body. The Mass brings about not just a new frame of mind, a new determination to do better, but a vital physiological change.

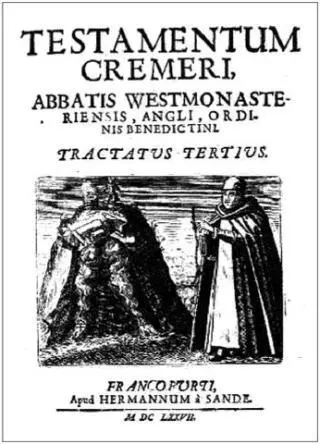

Title page of Testamentum Cremeri , showing Thomas Aquinas as a practising alchemist.

It is no accident that Aquinas formulated his doctrine at the same time that the stories of the Grail began to circulate. They describe the same process albeit using different methods.

Though they were enemies — Bacon mocked Aquinas for only being able to read Aristotle in translation — both Aquinas and Bacon were representatives of the impulse of the age: to strengthen and refine the faculty of intelligence. They found magic in thinking. The capacity for prolonged, abstract thought, for juggling with concepts, had existed once before but only briefly and locally in the Athens of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, before being snuffed out again. A new, living and more long-lasting tradition arose with Aquinas and Bacon. Both put experience before the dead old categories of tradition, and both were deeply religious men who sought to refine their religious beliefs on the basis of experience. ‘Without experience,’ said Bacon, ‘it is impossible to know anything.’

Bacon was the more practical, but when he explored the mind’s supernatural capacities, he invoked entities from the same spiritual hierarchies that Aquinas categorized. Both applied rigorous analysis and logic, and their mysticism was quite unlike the unthinking, ecstatic mysticism of the Cathars.

A young scholar at Oxford in the 1250s, Roger Bacon resolved, like Pythagoras before him, to know everything there is to know. He wanted to gather together into his own mind all that the scholars at the court of Haroun al Raschid had known.

Roger Bacon became the image of a wizard. Known as Doctor Mirabilis, he sometimes appeared on the streets of Oxford in Islamic robes. At other times he worked without rest day and night in his rooms in college which would be rocked by explosions from time to time.

Bacon busied himself conducting practical experiments, for example with metals and magnetism, discovering gunpowder independently of the Chinese or scaring his students by shining a light on to a crystal in order to produce a rainbow — something which up until that time people had believed only God could do. He also had a magic looking-glass that enabled him to see fifty miles in any direction, because he, unlike anyone else alive at the time, understood the properties of lenses.

Читать дальше