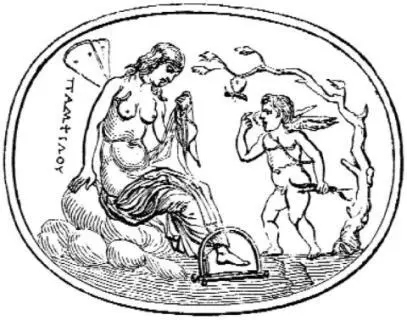

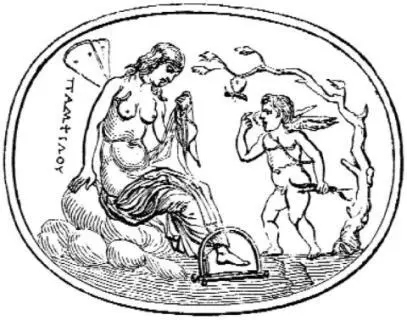

Psyche is a beautiful, innocent young girl. Cupid falls in love with her and sends messengers asking her to come to him in his hill-top palace at night. She is to make love to a god! But there is one condition. Their love making must take place in total darkness. Psyche must take it on trust that she is enjoying the love of a god.

Her elder sister is envious, though. She taunts her and tells her that it is not a beautiful boy-god she is making love to, but a hideous, giant serpent. One night Psyche can resist no longer, and while Cupid is in a post-coital slumber, she holds an oil lamp over him. She is delighted to discover the gloriously beautiful young god, but at that moment a drop of burning oil falls on him and wakes him. Psyche is banished from his presence forever.

The double meaning in this story is this: the god really is a hideous serpent. This is the history of the Nephilim, of the entry into the human condition of the serpent of animal desire — but told from the human point of view!

THE MYSTERY SCHOOLS WERE FALLING into decay. As we have seen, excavations of the entrance to the Underworld at Baia in southern Italy revealed secret passageways and trap doors used to help convince the candidates that they were having supernatural experiences. In the smoky, druggy darkness priests dressed up as gods would loom out of the darkness over candidates heavily drugged with hallucinogens. Robert Temple has reconstructed the initiation ceremonies of this late, decadent phase. They were largely a matter of scary special effects, even including puppets, like a ghost train today. The difference was that at the end of your initiation, when you re-emerged into daylight, the priests quizzed you, and unless you believed in their illusions without the slightest sliver of doubt, they killed you .

The Golden Asse which contains the story of Cupid and Psyche is a beautiful book, written by an initiate in a larky way that anticipates Rabelais. But it is also a consciously literary production. The colossal and monolithic sincerity of the ancient Mystery schools is no more.

The sincere men of Rome, the true initiates, withdrew into yet more shadowy schools that operated independently of the official cult. Stoicism became the outward expression of the initiatic impulse of the age, the growing point of intellectual and spiritual evolution. Cicero and Seneca, both deeply involved with Stoicism, tried to temper the egomania of their political masters. They tried to argue that all men were born brothers and that the slaves should be set free.

Cicero was an urbane and sophisticated man and one of the great forces for reform in the Roman Empire. He looked upon his initiation at Eleusis as the great formative experience of his life. It had taught him, he said ‘to live joyfully and to die hopefully’.

If Cicero looked askance at the plebs’ vain and superstitious beliefs in venal gods, he was also tolerant of them. He held that even the most ridiculous of the myths could be interpreted in an allegorical way. In The Nature of the Gods he gives a passionate exposition of the Stoic idea of the moving spirit of the universe, the guiding force that makes plants seek nourishment in the earth, gives animals sense, motion and an instinct to go after what is good for them that is almost akin to reason. This same moving spirit of the cosmos gives people ‘reason itself and a higher intelligence to the gods themselves’. These gods should not really be imagined as having bodies like our own ‘but are clothed in the most ethereal and beautiful forms’. He writes, too, that ‘we can see their higher, inward purpose in the movements of the stars and planets’.

When Rome’s political machinations finally caught up with Cicero, he stoically bared his neck to the centurion’s sword.

Seneca also believed in this cosmic sympathy of the Stoics — and the ability of adepts to manipulate this sympathy for their own ends. His play Medea probably quotes real magical formulae used by the black magicians of the day. Medea is portrayed as being able to direct her power of concentrated hatred so strongly that she can change the positions of the stars.

In this Age of Disenchantment it first became possible to consider that the gods might not exist. Among the intellectual elite, the Epicureans were formulating the first materialistic and atheist philosophies. What remained was belief in the lowest levels of spirits, the spirits of the dead and demons. If you read literature of the time, such as the Gospels of the New Testament, you see they record that the world was experiencing an epidemic of demons.

While the intellectual elite toyed with atheism, the people dabbled in atavistic forms of occultism that made use of the fact that demons and other low forms of spirit life are attracted by the fumes from blood sacrifices.

The high priest of the Jerusalem Temple wore little bells attached to his robes so that the goblins that lived in the shadows could hear him coming and hide their hideous shapes. The Temple needed a vast, complex drainage system to cope with the thousands of gallons of sacrificial blood that flowed through it every day.

All around the world increasingly desperate measures were taken. Plutarch wrote against human sacrifice in a way that implies it was common.

In South America, in a bizarre parody, a black magician was being nailed to a cross.

15. THE SUN GOD RETURNS

The Two Jesus Children • The Cosmic Mission • Crucifixion in South America • The Mystic Marriage of Mary Magdalene

IN PALESTINE A GREAT TURNING POINT IN the history of the world had been reached. Because the gods were no longer experienced as ‘out there’ in the material world, it was necessary for the Sun god, the Word, to descend to earth. As we are about to see, his mission was to plant in the human skull the seeds of an interior life that would become the new arena for spiritual experience . This planting would give rise to the sense we all have today that we each have inside an ‘inner space’.

The cosmic plan had been that human spirits should attain individuality, should be able to think freely, to exercise free will and to choose who to love. To create the conditions for this, matter became denser until each individual spirit was finally isolated inside its own skull. Human thought and will was then no longer wholly controlled by gods, angels and spirits, as it had been a thousand years earlier at the siege of Troy.

However there were dangers in this development. Not only might humanity become altogether cut off from the spirit world, there was a danger, too, that humans would become completely cut off from one another.

This was the great crisis. People no longer felt like spiritual beings, because the human spirit was in danger of being snuffed out altogether. The love that bound tribes and families, an instinctive, psychic blood-love like the one which binds packs of wolves, was weakened in the newly hardened skulls, in the new towns and cities.

Tracing the development towards a sense of individual identity, we have touched on Mosaic law, a rule for communal living strictly enforced, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. We have touched, too, on the obligation to feel compassion for all living things taught by the Buddha. We saw in both traditions the beginnings of moral obligation as a path of individual discipline and development. Now the Stoics of Rome gave the individual legal and political status in the form of rights and duties.

The irony, then, was that just as individual human identity was formed, the sense that life was worth living was largely lost. The blood baths in the Colosseum showed no notion of the value, let alone the sanctity of individual human life.

Читать дальше