After the Flood, Dionysus the Younger, often depicted in a boat, travelled from Atlantis via Europe to India, with the aim of teaching the whole world the arts of agriculture, the sowing of crops, the cultivation of the vine and writing. This latter had of course been taught by Enoch, but was now in danger of being lost in the devastation brought by the Flood.

Dionysus and his followers carried the thyrsus, a pole wrapped with ivy-like snakes and topped with a pine cone like a pineal gland. This shows that Dionysus also taught the secret evolution of the human form, the development of the spine topped by the pineal gland we have just been considering.

The fauns and satyrs and the whole rout of Dionysus represent stragglers from Atlantis. They are the last remnant of a process of metamorphosis of forms. The curious story in Genesis of Noah’s sons uncovering his genitals while he was drunkenly sleeping also refers to the petering out of this process. We saw that the genitals were the last parts of human anatomy to evolve into their present form, and his sons were curious to find out about their origins. Were they the sons of a human or a demi-god, a man or an angel?

Noah’s ark. Legend has it that the only animal that missed the ark was the unicorn, which therefore became extinct. This is an obvious depiction of the diminishing of the powers of the Third Eye. As the waters of the deluge closed over Atlantis, the era of Imagination ended. The subconscious was formed .

Dionysus the Younger was educated by the satyr Silenus.

Stories about this individual in the Greek and Hebrew traditions — Dionysus the Younger and Noah — are both connected with the grape and intoxication. We have already met followers of Dionysus. The wild and savage maenads tore Orpheus limb from limb with tooth and nail. In a state of ecstatic drunkenness the maenads were possessed by a god.

PRIMITIVE PEOPLES HAVE ALWAYS LIVED in tune with the vegetable part of their natures. One of the results of this is that they have understood how different plants have different effects on human biology, physiology and consciousness.

What we see in these Greek and Hebrew traditions of the beginnings of agriculture is a depiction of a new, more thoughtful form of consciousness. What greater outward symbol of the impact of orderly human thought on nature could there be than fields of wheat?

The task of the leaders of humanity would now be to forge the new thought-directed consciousness.

In the Zend - Avesta , the sacred literature of Zoroastrianism, the Noah/Dionysius figure is called Yima. He tells the people how to build a settlement — a ‘var’- a fenced-in place, a kind of stronghold ‘taking in men, cattle, dogs, birds and blazing fires’. He instructs people that when they arrive at the place where they are to settle, they must ‘drain off water, put up boundary posts, then make houses from posts, clay walls, matting and fences’. He urges his people to ‘expand the earth by tilling it’. There was to be ‘neither suppression nor baseness, neither dullness nor violence, neither poverty nor defeat, no cripples, no long teeth, no giants, neither any of the characteristics of the evil spirit’.

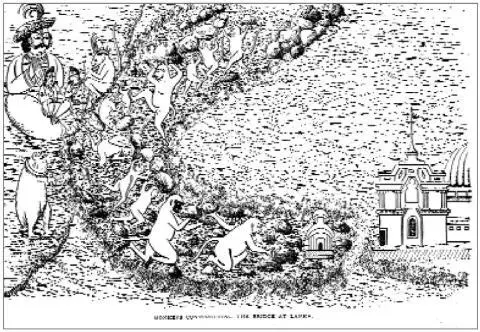

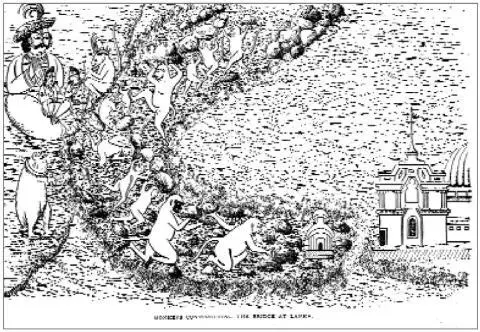

The invasion of Ceylon by Rama, the ‘shepherd of the peoples’.

Again, we see an anxiety about a reversion to anomalous forms of the previous epoch such a giants.

The Greek epic poet Nonnus described Dionysus’s migration to India, and the same journey is also described in the Zend-Avesta as ‘the march of the Ram on India’. But the fullest description comes in the great Indian epic, the Ramayana .

Something that is clear from these accounts is that the great migrations eastwards were not moving into uninhabited territories. While the peoples of Atlantis had been all but eliminated, the emigrants travelled to new lands still occupied by aboriginal tribes. We see Dionysius’s reaction to what he found in these new lands in his forbidding of cannibalism and human sacrifice. Native priests would sometimes keep enormous snakes or pterodactyls, rare survivors from antediluvian times, which were worshipped as gods and fed the flesh of captives. The Ramayana describes how Rama and his followers suddenly invaded these temples with torches, driving out both priests and monsters. He would appear without warning among enemies, sometimes with bow drawn, sometimes defenceless except that he was able to petrify them with his pale lotus-blue gaze.

Rama was dispossessed, a nomad. His kingdom lay beneath the seas. He did not live the life of a king, but camped out in the wild with his beloved Sita.

Then Sita was abducted by the evil magician Ravana. The Ramayana tells of the completion of Rama’s journey with the conquest of India and the taking of Ceylon, the last refuge of Ravana. Rama formed a bridge over the sea between mainland India and Ceylon with the help of an army of monkeys, which is to say hominids, the descendants of human spirits who had rushed into incarnation too early and were doomed to die out. Finally, after a battle that lasted thirteen days, Rama killed Ravana by showering fire down on him.

We might see Rama as a Neolithic Alexander the Great. Following the conquest of India, he had the world at his feet. He also had a dream.

He was walking in the forests on a moonlit night, when a beautiful woman came towards him. Her skin was as white as snow and she was wearing a magnificent crown. He didn’t recognize her at first, but then she said, ‘I am Sita, take this crown and rule the world with me.’ She knelt humbly and offered him a glittering crown — the kingship which had been denied him. But just then his guardian angel whispered in his ear: ‘If you place that crown on your head, you will see me no more. And if you clasp that woman in your arms, she will experience such happiness that it will kill her instantly. But if you refuse to love her she will live out the rest of her life free and happy on earth, and your invisible spirit will rule over her.’ As Rama made up his mind, Sita disappeared amongst the trees. They would never see each other again, leading the remainder of their lives apart.

Stories about Sita’s later life suggest it was by no means obvious that she was as happy as the guardian angel had promised. In its ambiguity and uncertainty there is something very modern about this story.

We can also see in it a paradox that lies at the heart of the human condition. All love, if it is true love, involves a letting go.

With his prowess with the bow, his handsome face, blue eyes and lion chest, Rama is in many ways like the heroes that Greek myths describe, such as Hercules, but in the story of Rama there is, as I say, something new. Hercules was required to choose between virtue and happiness, and unsurprisingly chose the former. Rama’s story, on the other hand, contains an element of moral surprise . The reader of the story will probably agree with Sita as she argues with Rama that it is only right and fitting that he now accept the crown he has been cheated of since birth. But then Rama’s surprising choices — deciding not to take the crown that is rightfully his, not to marry the woman he loves — these dilate the moral imagination and quicken the moral intelligence. The story of Rama encourages us to see beyond the conventional, to imagine ourselves into the mind of others and also, ultimately, to think for ourselves. Esoteric thinking has always sought to undermine and subvert conventional, habitual, mechanical modes of thought. Later we will see how storytellers, dramatists and novelists steeped in esoteric thought, from Shakespeare and Cervantes to George Eliot and Tolstoy, would quicken the moral imagination, one of the distinguishing characteristics of the very greatest literature. If great art and literature give a sense of patterns, of laws operating beyond conventional thought, great esoteric art brings these laws near to the surface of consciousness.

Читать дальше